Regional Dimensions of Ukrainian Civil Society

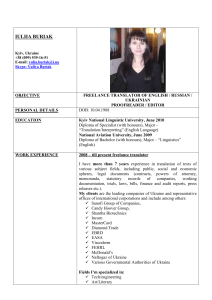

advertisement