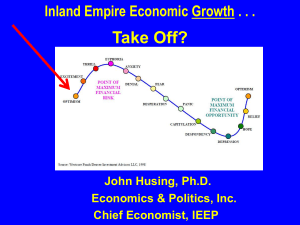

San Bernardino Community College District

advertisement