Cognitive and S-R Interpretations of Incentive

advertisement

Back to Realism Applied to

Home Page

Cognative_SR.doc

Furedy, J.J., and Champion, R.A. (1963). Cognitive and S-R interpretations of

incentive-motivational phenomena. American Journal of Psychology, 76, 616-623

COGNITIVE AND S-R INTERPRETATIONS OF INCENTIVEMOTIVATIONAL PHENOMENA

By J. J. F UREDY and R. A. C HAMPION ,

University of Sydney, Australia

Following Bitterman's delineation of opposing predictions derivable from the

theories of Spence and Tolman,1 Gonzalez and Diamond obtained experimental

results which were interpreted as putting the differences between the two

theories in clearer perspective.2 Their most striking finding concerned two

groups of rats given a series of unrewarded trials in a runway, Rx, which was

dissimilar to the empty end-box, By. In a second stage, the members of one of

these groups (Group B) were directly placed and fed in Bx, a box similar to Rx

but unlike By, while the other rats (Group C) were fed in By. It was deduced

that, in a third stage of further unrewarded trials in Rx By, Spence should

predict faster running in Group B than in Group C, whereas Tolman should

predict the opposite result; the data were in accordance with the prediction

attributed to Tolman. While, however, Bitterman's deductions follow directly

from Spence's theory as explicitly stated,3 there remains the possibility that

Spence did not refer to some factors which might also be taken into account in

any further test of S-R theory, and the following study was designed to allow

for the possible role of two such factors.

In outline, Spence has supposed that when a goal-object such as food leads to a goal

response (Rg) in the end-box of a runway, cues (S2) temporally contiguous with Ro

come to elicit some component (rg) of this response through classical conditioning; if

stimuli in the starting box and runway (S1) bear any similarity to S2, then they may

elicit rg anticipatorily through stimulus-generalization, so that the stimulus-properties

of rg (sg) become part of the complex of stimuli eliciting the instrumental response of

running. By assuming that the intensity of s0 varies with the frequency and vigor of Rg,

Spence has envisaged a mechanism mediating the known activating effects of foodreward. It is not a necessary feature of this model, however, that sg should come to

elicit the particular instrumental response under scrutiny by an experimenter, for if

some response other than running should be dominant in the runway-situation, then sg

could well come to form part of the complex eliciting this competing response and so

interfere with the response being

* Received for publication December 7, 1961.

M. E. Bitterman, Review of Spence's Behavior Theory and Conditioning, this JOURNAL,

70, 1957, 141-145, esp. 144.

2

R. C. Gonzalez and Leonard Diamond, A test of Spence's theory of incentive-motivation, this

JOURNAL, 73, 1960, 396-403.

3

K. W. Spence, Behavior Theory and Conditioning, 1956, 134-136.

1

INCENTIVE-MOTIVATIONAL PHENOMINA

617

measured. It is emphasized that, according .to this elaboration of Spence's hypothesis, it is not the hypothetical r g but some overt response which is

thought to compete with the instrumental response under study. The

experiment of Gonzalez and Diamond began with a series of unrewar ded trials

in a 48-in. runway, the running times being of the order of 40 sec, and these

times increased slightly over the first set of trials, suggesting that competing

responses were strong. This, therefore, was the first factor which the present

study sought to control, by the use of rewarded trials in the first stage so as to

ensure the clear dominance of the running response.

To make a complete application of Tolman's type of theory to the data of their

study, Gonzalez and Diamond extended the theory by supposing that directplacement feedings in Bx, for example, acted not only to increase the valence

of the stimuli in Bx as an end-box (S 2 ) but also the valence of the cues in Rx

(S 1 ), because of their similarity to S2. Thus the performance of Group B should

have been interfered with by direct feedings in Bx because of the similarity of

Bx to Rx and the dissimilarity of Bx to By, making the valence of the stimuli in

By (S 2 ) relatively less than that of the stimuli in Rx (Si). It can be shown, on the

other hand, that S-R theory leads to such an expectation without any extension.

According to Spence's hypothesis, the direct-placement feedings in Bx or By cause

rg to be elicited by the stimuli there (S'2) so that, other things being equal, rg

should occur more strongly in Rx with feedings in Bx because of the greater

similarity between Bx and Rx than between By and Rx. But again the model does

not require that only rg is conditionable to S'2, and it must be recognized that under

the somewhat unusual direct-placement conditions the cues in Bx and By may

come to elicit a variety of other overt responses which might be loosely

characterized as 'looking for food/ that these will transfer to Rx more from Bx

than from By, and that performance could well be inferior in Group B for this

reason. This transfer could also occur under normal runway-training conditions,

as Hull envisaged, 4 but the competing responses are assumed to become

subordinate to the reinforced instrumental response of running. The r g , on the

other hand, is also transferred, but is thought of as incapable of competing with

any overt response. To make some allowance for this second factor which

emerged from a more detailed consideration of S -R theory, an attempt was

made to reduce competing, overt ('looking-for-food') responses to a minimum by

sounding a tone whenever 5 entered a goal-box containing food (Bx or By), this

stimulus not being presented while 5 was in Rx. In Skinner's terms, it was

intended that the tone should become a discriminative stimulus for food. The

use of this stimulus should not have destroyed the rationale of the experiment,

the similarity between Bx and Rx still being greater than that between By and

Rx (Spence), with the relative valence of By still greater than that of Bx

(Tolman).

Method: ( 1 ) Subjects. The Ss were 16 experimentally naive male albino rats,

ranging in age from 83 to 107 days at the beginning of preliminary training.

(2) Apparatus. The apparatus was similar in function to that used by

Gonzalez and Diamond, but it differed in structural detail. There were two

runways, 5 in. wide, 24 in. long, and 5 1 / 2 in. high. One runway had white

walls and a wire4

C L. Hull, A Behavior System, 1952, 124-125.

618

FUREDY AND CHAMPION

covered aluminum floor, while the second runway had black wails and an uncovered floor. There were also four boxes, 5 X 6 l/ 2 X 5 l / 2 in., which could be

used interchangeably as starting boxes or end-boxes, two similar to the white runway and two similar to the black runway. Another set of four boxes, identical

with the first set except for their greater length of 9l/2 in., was used in the second

replication because the Ss were older and larger. The runways and boxes were

covered with clear perspex. The boxes were separated from the runways by means of

transparent guillotine-doors, while the interior of each goal-box was hidden from

the runway by an opaque curtain on the runway-side of each door. When E lifted

the door between the starting box and the runway a micro-switch was automatically

closed so as to start an electronic chronoscope, and the passage of the rat's body across

a gap in the metal floor between starting box and runway activated a relay which

stopped the chronoscope, thus giving a measure of starting time. Running times

were measured less precisely, with a stopwatch. Another microswitch was linked

with the door between the runway and the goal-box, so that when E closed this

door as S entered the goal-box, a 500-cpsec. 85-db (spl) tone was sounded for 5

sec.

(3) Procedure. The experiment was conducted in two replications, with 6 Ss

in the first and 10 Ss in the second.

(4) Preliminary training. For the first 10 days the Ss were put on a 24-hr,

feeding schedule, handled for 5 min. daily, and allowed to eat for 1 hr. On the

eighth day the food was changed from dry pellets to wet mash. An equal number

of Ss was assigned to the white and black runways, and they were allowed to explore

the apparatus with the doors open, no food-reward, and with no tone, for 5

min. daily until all Ss were readily crossing into the goal-box through the curtain.

This pretraining was conducted immediately prior to the daily eating session; it

took three days for the first replication and six days for the second replication.

Stage 1. After at least 2 min. of adaptation in the experimental room, each S

was given training trials in the appropriate runway, as follows. When S oriented

towards the door of the starting-box, the door was opened by E and then lowered

after S had passed into the runway, so as to prevent retracing. When S passed

through the curtain into the goal-box, the second door was lowered, to prevent

retracing, and the tone sounded for 5 sec. The reward for each trial was approximately 2 gm. of wet mash, half food and half water by weight. As soon as S

finished eating (after approximately 1 min.), it was replaced in the starting box

for the next trial. The Ss were given 4 trials on each of two days, being allowed to

eat wet mash ad lib for 30 min., starting at least 30 min. after the 4th trial each

day.

Stage 2. On the basis of mean starting times over the last 4 trials of Stage 1,

the two main Groups B and C were established by matching the Ss in pairs, with

the restriction that half the Ss in each group be trained in the white and half in the

black runway. Then the Ss were given direct-placement feedings, either in a box

similar to the starting box and runway of Stage 1 (Bx, Group B) or in the goal-box

of Stage 1 (By, Group C). After 3 min. of adaptation in the experimental room each

S was placed directly into the box containing approximately 4 gm. of wet mash

(50% dry food by weight) and the tone was sounded for 5 sec. As soon as 5

had finished eating, it was returned to the holding cage for 1 min. and

INCENTIVE-MOTIVATIONAL PHENOMINA

619

then replaced in the box for a further period of eating. The Ss were fed four

times on each of four days in this fashion, and once on the fifth day. On the first

four days the Ss were allowed to eat mash ad lib for 30 min., beginning at least

30 min. after the last direct-placement feeding, but on the fifth day the single

feeding in the box was followed by the first four trials of Stage 3. By making

small adjustments in the amount of mash presented in the box over the 17 trials

of Stage 2, it was ensured that the average time spent in eating in the goal box

per trial by each S was approximately 120 sec. (ranging from 117 to 126 sec.) and

that the average times for Groups B and C were equal at 120.7 sec. As al ready

noted, care was also taken to see that the entire time in the goal -box was spent in

eating, in both Stage 1 and Stage 2.

Stage 3. After the direct-placement feeding on the fifth day of Stage 2, all Ss

were removed from the experimental room. At least 15 min. later they were re turned to the room, allowed 2 min. of adaptation, and then given 4 trials in the

manner of Stage 1. A further 4 trials were given on the next day.

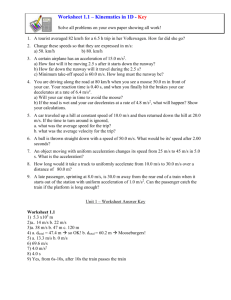

F IG. l. PERFORMANCE IN THE SECOND HALF OF S TAGE l AND IN S TAGE 3

Results. The performance of the two Groups B and C on the last 4 trials of

Stage 1 and the 8 trials of Stage 3 is plotted in Fig. 1, in terms of mean startingtime. The running times showed the same trends as a measure of performance,

but were more variable than the starting-times. Taking the first block of two

trials in Stage 3 as a measure of the effects of Stage 2, the individual mean

starting-times (sec.) were as follows. Group B: 4.00, 2.50, 1.95, 1.80, 1.65,

1.60, 1.60, and 1.45; Group C:

620

FUREDY AND CHAMPION

0.85, 0.75, 0.70, 0.65, 0.60, 0.58, 0.50, and 0.50. Since there was no

overlap in these two samples, no statistical test was deemed necessary, the

performance of Group C being clearly superior. It may be observed in Fig. 1,

however, that the difference between the two groups had all but disappeared by

the second block of two trials in Stage 3.

Discussion. The chief impression provided by the data of this experiment is

that of further support for Tolman's position, in view of the clear superiority of

Group C in the early trials of Stage 3. It is generally accepted, however, that a

theory is rarely demolished by the results of a single experiment, as a crucial

instance, but rather tends to give way gradually to a superior theory. Since S-R

theory appears to offer the most potent alternative to a cognitive interpretation

of the data, the remainder of this discussion is devoted to the chief comments

still open to the S-R theorist and to possible defects in the present study.

It will be recalled that the experiment was designed to ensure: first, that the

instrumental response of running was dominant at the end of Stage 1, so that

further increase in the strength of rg in Stage 2 would not activate some

competing response; and secondly, that 'looking-for-food' responses generated

in Stage 2 would not transfer to the starting box and so constitute another form

of competition with running as measured in Stage 3. Whereas the first of these

aims was easily achieved, it is felt that some doubts must be held about the

effectiveness of the tone as a discriminative stimulus. Indeed, the search for an

effective means of preventing the generation of competing responses in Stage 2

leads the S-R theorist to a dilemma. If the feeding-box stimuli (S'2) of Stage 2

and the stimuli of starting box and runway (S1) are made identical, then

although rg may be strengthened in the former and transferred to the latter

situation, competing responses may also be transferred, being made all the

stronger by the dynamogenic effects of rg. If S1 and S2 are made quite dissimilar

on the other hand, then not only the undesirable competing responses but also

the activating rg may fail to transfer. In the present experiment a compromise

was sought by presenting the tone in S'2 (feeding box) and S2 (goal-box) only

for the first 5 sec., while the animal was moving towards food, and by not

sounding the tone for any length of time during actual eating, when rg was

presumably occurring. If this technique failed in its purpose, however, then the

performance of Group B would have been depressed in comparison with that of

Group C, because of the greater similarity of Rx to Bx than to By, and this was

the obtained result

In examining the results of the present study, attention was concentrated upon the

comparison of Groups B and C within Stage 3. This was done in the belief that

INCENTIVE-MOTIVATIONAL PHENOMINA

621

comparisons between levels of performance at different stages have no relevance to the

comparison of the theories of Tolman and Spence. It might be suggested that some

meaning could be given to between-stage comparisons by the use of a control group of

Ss given no direct-placement feedings in Stage 2 but simply held in their home cages

and given normal daily feedings. The irrelevance of between-stage comparisons and

the ineffectiveness of this control group may be demonstrated by consideration of the

following possibilities in terms of Fig. 1. First, taking the data at face-value, the

performance of Group C was relatively unaffected by the events of Stage 2 whereas

that of Group B was considerably impaired. The comparable result for Group C in the

study of Gonzalez and Diamond was a marked increase in response strength, and the

failure to obtain such an effect in the present case may have been due to the use of

reinforced trials in Stage 1, which alone could have brought performance near a

maximum. It is not usual for 8 trials to suffice for this purpose in runway-training, but

further evidence for the possibility is to be found in the fact that Group C showed no

further improvement in the course of Stage 3. As far as Group B is concerned, the

modified cognitive theory would account for the decrease in response-strength by

reference to the superior valence of the runway (Rx) relative to the goal-box (By) as a

result of feedings in a box similar to the runway (Bx) in Stage 2. An S-R theorist, on

the other hand, could suggest that the tone failed to act as a discriminative stimulus, so

that the direct-placement feedings in Bx simply led to the occurrence of competing

responses in Rx in Stage 3. It could even be suggested that the use of the tone was illadvised in that, as a result of differential conditioning, it prevented transfer of rg to the

starting box and runway by its absence there. The answer to this claim, however,

would seem to lie in the substantial improvement in performance which occurred in

Stage 1, under conditions where the tone was present briefly in the goal-box but never

in the runway.

Instead of taking the data at face-value, it might be allowed that some forgetting

would occur in a group which did not have any direct feedings in Stage 2, enough to

locate such a control group somewhere between Groups B and C at the beginning of

Stage 3. If this were the case, the cognitive and S-R theories would seem to apply

equally well to the data, for both could predict improvement in Group C and

impairment of performance in Group B as a result of the direct-placement feedings.

Assuming that the position of the cognitive theorist has already been made clear, the

reason for such an expectation on the part of the S-R theorist may need elaboration. If

the reinforced trials of Stage 1 are to have any effect then it must be through the Rg-Sg,

mechanism as outlined above; i.e. the rg comes to occur anticipatorily in Rx through

stimulus-generalization from By, for although Rx and By differ in important respects

they still bear some degree of similarity to each other. This being so, direct feedings in

By should lead to some further improvement in performance in Stage 3, provided that

performance has not already reached a maximum by the end of Stage 1 or allowing

that some forgetting would have occurred otherwise, after the end of Stage 1. It is to be

presumed that the feedings in By would not cause competing responses in Rx, for

otherwise the learning in Stage 1 would not occur so readily. In the case of Group B,

on the other hand, the S-R theorist may argue as for the face-value case.

If this line of argument were followed to the limit it is conceivable that a control

group denied feedings in Stage 2 could deteriorate in performance to the same ex-

622

FUREDY AND CHAMPION

tent as Group B did in the present study (Fig. 1). Under these conditions it would be

concluded that the interpolated feedings in Bx had no effect, whereas feedings in By

led to considerable improvement in Group C, as found by Gonzalez and Diamond.

Even so, the S-R theorist could suggest that feedings in Bx produced opposed factors

which counter balanced each other in Group B, while the activating effects of rg were

free to show in the performance of Group C. It should be emphasized at this point that

Spence's statement of his version of the S-R position does not explicitly refer to these

theory-saving possibilities, and that the critics of this position have proceeded along

perfectly proper lines in their interpretations of the theory as stated. Nevertheless, it is

felt that an objective assessment of the position should exhaust every possibility.

In the light of these comments arising from a consideration of the present

data, some general findings and interpretations of Gonzalez and Diamond may

be reexamined briefly. These Es have suggested that, according to S-R theory,

the performance of groups fed in a box (Bx) similar to the starting box and

runway (Rx) (their Groups A and B) should be superior to that of groups fed in

a box (By) dissimilar to the rest of the alley (their Groups C and D). Now

whereas this type of interpretation may be applicable to the usual runwaytraining situation, in a comparison of groups trained with Rx Bx and Rx By, it

may be rendered invalid in the less usual, direct-placement situation by the

generation of competing ('looking-for-food') responses in Rx with placements

in Bx. Although this possibility was not allowed for by Spence in his brief

outline of an experiment,5 and not recognized at the outset by Stein when he

conducted the experiment,6 it need not be precluded from serious consideration.

A second implication of S-R theory for Gonzalez and Diamond was its failure

to account for effects obtained with variations in the similarity of feeding box

(S'2) to goal-box (S2) with the relationship of S'2 to starting box and runway (S1)

held constant. It is suggested, however, that their experiment has not produced

clear evidence of the existence of such effects, in the form of statistically

significant differences in Stage 3 between Groups A and B, and between

Groups C and D. Finally, it bears repetition that the cognitive interpretation

derived from Tolman completely encompasses all the findings.

SUMMARY

An experiment was conducted which sought to check the results of two groups used in an

earlier study of Gonzalez and Diamond. These were

5

Spence, op. cit., 147-148.

.

6

Larry Stein, The classical conditioning of the consummatory response as a de terminant

of instrumental performance, J. comp. Pbysiol. Psychol., 50, 1957, 269-278.

INCENTIVE-MOTIVATIONAL PHENOMINA

623

groups given a preliminary test without reinforcement in straight-alley

apparatus with a goal box (By) dissimilar to the starting box and runway (Rx)

and then given direct-placement feedings in a box (Bx) similar to Rx (Group B)

or in By (Group C). The reason for this replication was the attempt to allow for

the possible non-dominance of the instrumental, running response and for

competing responses generated in the direct feedings in Bx and generalizing to

Rx in a later test. Allowance was made for these factors by using reinforced

trials before the direct feedings and by sounding a tone with all entries into Bx

or By, as a discriminative stimulus for food. The result (Group C superior to

Group B) was in keeping with a cognitive interpretation of the phenomena

(Tolman), as proposed by Gonzalez and Diamond, but further features of an SR interpretation (Spence) were considered and not excluded.