Cognition and the Fractional Anticipatory Goal Response

advertisement

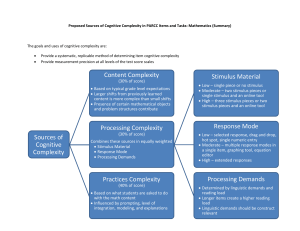

Back to Realism Applied to Home Page Cognition and fractional.doc Cognition and the Fractional Anticipatory Goal Response (1963 talk stating the specific and empirically meaningful difference between cognitive and noncognitive psychological functions) Text of 1963 paper given by John Furedy at the Annual Meeting of the British Psychological Society, Melbourne One of the important functions of the fractional anticipatory goal response in Spence’s neobehaviorist (S-R) theory is that of being a substitute for cognition, knowledge of propositions of the “not here” goal box. So, in the ordinary runway situation, the fractional anticipatory goal response (rg) “transports”, as it were, the “not here” goal box (which is invisible), and its reinforcing properties back to the start box and alley. Hence the animal runs faster and faster out of the start box as a function of reinforced trials even though, each time it is placed in the start-box, the goal-box, being invisible, is not present to the animal. DIAGRAM 1 IS TAKEN FROM SPENCE’S BEHAVIOR THEORY AND CONDITINNG, 1956, p. 134. (explain how rg, which activates RLOC, occurs to Sa through stimulus generalization from the “not here” SG). A cognitive theory, of course, deals easily with this problem of the “transportation” of the “not here ”goal box the cognizing rat, the rat which has Tolmanian expectancies, simply knows the proposition that, “this start box is a sign of that (good) goal box” (the goal box being good or having a high valence because it contains food). Now given the rg does have this function of doing the work of cognition or expectancies in the matter of transportation, one can ask how good a substitute it actually is. And in this connection, although there have been extensive and severe theoretical criticisms of the rg, criticisms, that is, which cast doubt on its value ass a scientific construct, there has been little criticism of an empirical nature. Thus even Meehl and McCorquodale, who, from a theoretical point of view, issue the ultimate condemnation of the rg by labeling it a dues ex machina mechanism, appear to rule out the possibility of an empirical criticism by their comment that, “the basic cognitive element, the forward pointing reference of the expectandum term is smuggled inky invoking the rg”. Granted, the term “smuggled in” may not be a particularly complementary one. But it still seems to suggest that, empirically speaking, speaking, that is, form the point of view of prediction, or consistency with matters of behavioral fact, Spence’s rg can predict all that can be deduced form a cognitive construct, since, with the aid of the rg, Spence can “smuggle in” the “basic cognitive element”. Now the importance of the work of Gonzales and Diamond is that it seems to negate the view that this smuggling is a perfect crime, the view that, in terms of behavior, there is nothing in the cognizing rat can do that the fractional-anticipatory-goalresponding rat cannot also do.. In that part of their experiment with which I shall be concerned, the following procedure, which I have sketched on the board, was carried out. DIAGRAM 2 Groups Stage I Stage II Stage III B C RxBy RxBy Bx+ By+ RxBy RxBy Two groups of rats, B and C, were given a preliminary test without reinforcement in a straight-alley apparatus with a goal box (By) dissimilar to the starting box and runway (Rx), such Rx, By (the goal box) was invisible. This first stage was followed by direct-placement feedings in a box (Bx) similar to Rx (group B) or in By (group C). Thus, under stage II, we have no Rx for either group, indicating that the animals were simply placed in their respective goal boxes, and we also have the +symbols, indicating the presence of food in the goal boxes, one of which had x-type stimulus properties (for example white), while the other y-type stimulus properties (for example, black). The final, third, stage was a repetition of the preliminary test for both groups, in order to observe the effects of the differential treatment during the second, direct-placement stage. It was suggested by these experimenters that the effects of the second-stage treatment on the observable behavior, running speed, in the third stage, would be different according to whether the rats were cognizing in the Tolmanian fashion, or factional-anticipatory-goalresponding in the Spencian way. The rationale behind this claim can be stated as follows, using the symbol B_+ (WRITE) to stand for the baited goal box, with x or y stimulus properties, into which the animals were placed during stage II. From Tolman’s point of view, what is important is the B_+:By relationship, since it is the valence of the empty goal box, By, of Stage I, which must be raised for the rat to run faster during stage III, the rat having learned, during stage I, the expectancy or proposition that, Rx leads to (or is a sign of) By. Hence, since the B_+:By relationship is closer for the group fed in By+ (group C) than for the group fed in Bx+ (group B), a cognitive theory would predict that , at the beginning of stage III, group C runs faster from Rx than group B. So (WRITE UNDER DIAGRAM ii: Tolman – B_+:By imp., so C (fed in By+) faster than C (fed in Bx+). For the rg, on the other hand, as explicitly stated by Spence himself (Beh. Theory & Conditioning, pp. 147-8), what is important is the B_+:Rx relationship. For it is the closeness of this relationship which determines the intensity of rg evoked in to Rx by stimulus generalization from By+: (the place where rg occurs originally) to Rx. This is because, the more the similarity between the stimulus properties of B_+ and Rx, the greater the generalization from B_xt to Rx and hence, the greater the intensity of the rg evoked in Rx. Therefore, since the B_+:Rx relationship is closer for the group fed in Bx+ (group B) than for the group fed in By+ (group C), the S-R position, so it is argued, implies that, at stage III, group B runs faster from Rx than group C. So (write under diagram 2: Spence – B_+;Rx relationship imp., so B (fed in Bx+) runs faster than C (fed in By+). The results were clearly in accord with the predictions attrib9uted to Tolman: group C ran faster than B during the third stage. Now, as I shall argue later, in spite of Spence’s explicit statements to the contrary, a more detailed consideration of his theory, for which I am indebted to Professor Champion, shows that this experiment, as it stands, does not force Spence to predict a result that is different from that predicted by Tolman. The Gonzales and Diamond situation, contrary to appearances, is not one in which the cognizing animal and the responding animal need necessarily behave differently. Nevertheless, I think the work of Gonzales and Diamond to be of great importance, for by suitable modifications of the setup one can expect the cognizing animal to behave differently from the fractionally-anticipatory-goal-responding animal. And this is so, because, although Gonzales and Diamond have not explicitly made this point in their article, their approach bears on a crucial difference between responses and cognitions. Now the difference between responses and cognitions has often been often been thought to lie in whether the organism is influenced by what is not physically present to it at the time, the “not here” and the “not now”. But this distinction is not adequate; it is not the crucial difference for, as we saw at the outset, Spence can explain the influence of the not-her baited goal box in the ordinary runway situation without invoking the notion of cognition, since the properties of the invisible goal are carried back by means of the rg through stimulus generalization. Thus the stimulus generalization principle [which itself is based on the classical conditioning of responses] permits the organism to respond to the “not here”, while really being completely bound to the immediately present stimulus situation, the here and the now. An adequate distinction between the two notions, a crucial difference between responses and cognitions, is that cognition may involve propositional knowledge of, and not just response to the not here and the not now. That is to say, By, the goal box is known to the cognizing animal in the start box and runway (Rx), being present as part of the proposition that “This Rx is a sign of that By”. To put it more anthropomorphically, we might say that the cognizing animal is not surprised to see the goal box when he gets into it, since already in the start box he is aware of the thing by which is being influenced. Granted, this “awareness” distinction may not sound very important and, indeed, in the ordinary runway situation, it does not have any real bearing: the rat which is aware of the not-here goal box and the rat which is not, both behave in the same way; that is, that is, they both show an increase in running speed as a function of reinforced trials. But when, as in the Gonzales and Diamond approach, we separate the reinforcement (Stage II) and the goal box (Stage 1), this difference, this non-knowledge of By does become empirically important. For now, By, for the Spencian, fractional-anticipatory-goalresponding animal, is not present in any sense (not even in the ambiguous stimulusgeneralization or responded-to, sense). That is, the stimulus properties of By, for the Spencian animal, are quite irrelevant for his behavior (running speed) in the test stage III. It should also be clear that By, for Spence, is only artificially present in Rx in the ordinary situation, simply through association with the reinforcement. Thus the rgcognition distinction rests on the fact that the rg’s being responses to present stimuli, have no real “forward-pointing reference” in the Meehl-McCoquodale sense, since they do not involve a genuine (or rather cognizing relation to the not here. They involve only a stimlulus-generalization type of influencing. So the “smuggling” is seen as not a perfect crime, but the imperfection is brought out only through the Gonzales and Diamond approach of separating the goal box, m By (see stage I) and the reinforcement (see stage II). It is only through this separation, that it becomes possible to develop a situation where the behavior of the cognizing and fractional-anticipatory-goal-responding animal should be different. I have said develop deliberately. For, as I have already mentioned, as it stands, the Gonzales and Diamond situation, despite Spence’s explicit statement to the contrary, is not one which commits S-R theories to a prediciton different from Toman (i.e., C faster than B in stage III). And this is so because of at least two factors which, from an S-R points of view, could have worked against group B as to result in group B running slower than C. The first of these possibilities is that during the first stage (RxBy) the instrumental response of running may well have not been the dominant response since, unlike the ordinary situation, there was no reinforcement for running at this stage. Thus it could be that the greater rg’s generated in group B during the second stage were strengthening not the instrumental response of , RLOC (pint to diagram I), but the dominant competing, non-running response Room, say (PUT RCOM INTO DIAGRAM I).. For the rg strengthens or activates whatever response happens to be dominant. It just happens tube the case that I the ordinary (reinforced) situation, it is the instrumental response of running which is dominant. Arguing along these lines, the S-R theorist would not be abashed to find C running faster than B; he could simply say that the greater rg’s generated in B were causing that group to do other things faster or more energetically. Because of this first passivity, I used reinforced trials during stage I and III so as to ensure the clear dominance of the running response (PUT DIFFERENT COLORED +’s TO B’s ON DIAGRAM I). But even in this modified situation, there is a second possibility which could permit the S-R theorist to predict the cognitive result of C faster than B, and this is, that there is nothing to say that during the direct feedings in stage II, the only response that is conditioned to the stimulus properties of B_+ must be the rg. For it has to be recognized that under these somewhat unusual direct-placement conditions, the cues in B_+ may come to elicit a variety of other overt responses which might loosely be characterized as “looking for food”, that these will transfer more easily from Bx+ than from By+, and performance could well be inferior in group B for this reason. Now it did not seem possible to be sure of completely eliminating this “looking for food” response factor, if only because this response, like the rg, need not necessarily be observable. However, since this factor could only be used as a defence against having to predict B faster than C if it outweighs the influence of the rg factor, I decided to minimize the transfer of the looking for food response from the goal boxes to Rx by a discriminative stimulus technique of sounding a tone 5 seconds duration with all entries into the goal boxes. The final setup, then, was: (PUT IN T IN DIFFERNTCOLOR INTO DIAGRAM II). Comparing this situation with the original Gonzales and Diamond situation, we find that the essentials have been preserved, in that the degree of similarity between the goal box of the second stage (B_+t) and the goal box of he first stage (By+t) is still greater for group C than for B (important for Tolman), while the degree of similarity between the goal box of the second stage (B_+t) and the start box and runway (Rx) is still greater for group B than for group C (important for Spence). (PUT IN DIFF COLOR NEXT TO BOTTOM LINESIN DIAGRAM ii: +’s for By, t for all +’s. PROCEDURE After preliminary training to get accustomed to handling and to the apparatus, the rats were given 8 trials of four per day during stage I, 17 trials of four per day for four days and one on the fifth day constituted stage II. Stage II commenced on the same day and went for 8 trials at the rate of 4 trials per day. Without going into details, the basic aim in the procedure was to maximise the differences which were left after the necessary additions had been made to counter the possible S-R defences and to minimize irrelevant factors. This involved such things as emphasizing the x-y stimulus variation by pairing wire flooring with white and uncovered aluminum with black, extending the duration of the second stage, equating the average time spent eating for the two groups during stage (120.7 secs per trial) and allocating rats to the two groups only at the end of stage I so as to match the two groups for running speed. RESULTS The performance of the two groups B and C on the last 4 trials of stage I and the 8 trials of stagier I plotted I terms of meant starting time; see results in Furedy & Champion, 1963. Taking the first block of two trials in stage III as a measure of the effects of stage II, the individual mean starting times for the 8 animals in group B ranged from 4.00to 1.45 sec, while those for the 8 in group C ranged from 0.8 to 0.50 secs. Since there was no overlap in these two samples, no statistical test was deemed necessary, the performance of group C being clearly superior, though, as may be observed from the graphs, this difference had all but disappeared by the second block of two trials in stage III. DISCUSSION While the results as they stand are quite unambiguous, their implications, as is usual, are less so. For the S-R theorist could still defend his position by insisting that the discriminative stimulus procedure technique of pairing the tone with entries into the goal box did not minimize the transfer of the looking for food response to a sufficient degree for this factor to be outweighed by the rg factor. Or, he might well invoke some other part of the general theory which should have been, but was not, considered. And, although one may question the plausibility of these defences, it is nevertheless the case that they need not be precluded from serious consideration. But this sort of ambiguity, I suggest, is an invariant of any attempted “empirical arbitration” of this kind; no experiment can ever constitute certain falsification of any theory, but it can force the theorist to the dilemma of either having to give up his theory or having to suggest defences the plausibility of which is highly questionable This, I think, is all that can ever be achieved by an empirical arbitration, by what is sometimes called, the “crucial experiment”. I should also point out that I do not regard; this arbitration as in any sense being one between the theories in toto of Spence and Tolman, for on many other issues, I think the Spencian position to be highly preferable. What the experiment has done, rather, is to throw light on a specific and rather central bone of contention between the two theories: do organisms only respond or, do they, at least sometimes, also cognize. Now this issue, as I have said, has often been thought to be a merely theoretical one. What opened it to the possibility of experimental investigation is the realization that, as against Meehl and McCorquodale, rgs, being responses, have no real forward pointing reference. The “smuggling” is not a perfect crime for, the responding animal, although it may be influenced by, is not aware of, the “not here” and the “not now”.