Stridor - developinganaesthesia

advertisement

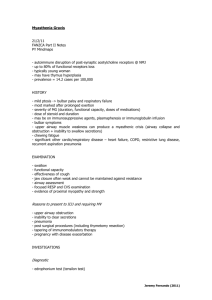

STRIDOR Introduction Inspiratory stridor (or noisy breathing on inspiration) may indicate an upper airway obstruction. Upper airway obstruction is a medical emergency. This can progress rapidly to complete airway obstruction and death from asphyxiation. As such stridor must always be recognized as a clinical sign of possible life threatening significance, and a cause should always be thoroughly investigated. The priorities in these cases (even before an exact diagnosis may be made) will be: ● Rapid clinical assessment ● Immediate intervention, where required. ● Close ongoing observation in an appropriate resuscitation area. ● Urgent referral to appropriate clinicians skilled in the management of an obstructed airway. Pathology Causes The causes of stridor include: 1. Infection: Space occupying abscesses and or inflammatory edema. Examples include: ● Peritonsillar abscess, (quinsy) ● Retropharyngeal abscess/ cellulitis ● Other deep neck abscesses 2. ● Epiglottitis, (may occur in adults, now rare in children who have been immunized against HIB) ● Croup, (in children). Allergic: Anaphylaxis: ● Airway edema due to an anaphylactic reaction. Although this is uncommon, (hypotension and wheeze are more characteristic). Angioedema: ● 3. Malignancy: ● 4. Either primary or secondary to drugs, (see separate guidelines). Tumours of the upper airway or adjacent structures Foreign bodies: In particular: 5. ● Elderly demented, (such as dental prostheses) ● The very young Altered conscious state: ● 6. Trauma: ● 7. Hematoma and/ or edema: Post surgical procedures of the neck or upper airway: ● 8. Reduced muscle tone of the upper airway musculature Hematomas or edema. Prolonged endotracheal intubation: ● Including larnygospasm on extubation. 9. Congenital abnormalities of the upper airway. 10. Psychogenic: ● Though this cause must always remain a diagnosis of exclusion. Clinical Assessment The clinical features of an upper airway obstruction include: 1. Noisy breathing, particularly on inspiration, (stridor). 2. Difficulty in talking. 3. Difficulty in swallowing. ● This may be to the point of “drooling” whereby the patient is unable even to swallow their own saliva. This is an important sign of significant obstruction. 4. A history of sudden chocking, (raising the possibility of an impacted foreign body in the airway or upper oesophagus). 5. Paradoxical respiratory efforts: 6. ● This is a serious sign of severe obstruction of the upper airway. ● The patient is in obvious respiratory distress. On inspiration there is intercostal or sternal retraction, whilst on expiration there is intercostal or sternal expansion, (the opposite of normal respiratory effort, hence “paradoxical” respiratory effort). Oral examination: ● A cautious examination of the mouth may be undertaken in adults, unless the patient is particularly distressed. ● Note however that oral examination is not recommended in distressed children, in particular where croup or epiglottitis is suspected, as increased distress may result in a worsening of upper airway obstruction. 7. Recent neck surgery, (there may be a post operative complication) 8. Vital signs: ● It is important to recognize that the vital signs, including a normal oxygen saturation level, may be completely normal, even in the presence of a significant upper airway obstruction. ● Fever will suggest an infective cause. ● 9. Abnormal respiratory rate, pulse rate or hypoxia on pulse oximetry or cyanosis are late signs and ominous of impending complete upper airway obstruction. Decreasing noisy breathing: Noisy breathing indicates some resolution of swelling or obstruction, however this sign needs to be assessed in the light of the overall clinical picture as it may also indicate a deterioration of the patient’s condition. ● When a patient progresses to complete airway obstruction, stridor and noisy breathing may cease because there is no further air movement at all. ● Alternatively the patient may be becoming fatigued and a decrease in stridor may indicate impending respiratory arrest. Investigation Investigation will usually be necessary to establish a firm diagnosis, however this should never delay definitive airway management when this is required. Depending on the stability of the patient and the index of clinical suspicion for any given condition the following may be required: Blood tests: 1. FBE 2. CRP 3. U&Es/ glucose 4. Blood cultures. Radiography: In stable patients a plain soft tissue lateral radiograph of the neck may be useful, in particular for suspected foreign bodies or retropharyngeal abscess. CT scan: This is an excellent imaging modality for the neck, and may be undertaken in patients with stable airways, however in patients with stridor or who are unstable then the investigation is far more problematic, as these patients cannot lie flat. Each case needs to be assessed on its merits but in general terms the airway should be secured before CT scanning is attempted. Management It is critical to anticipate problems before the patient’s airway becomes completely obstructed and to mobilize expert medical help quickly. In general terms: 1. Initial general measures: Positioning: ● Support the patient in their preferred position for breathing. An upright position is preferred. Generally these patients will be reluctant to lie flat as this tends to exacerbate an upper airway obstruction. Give oxygen if required: ● Nasal prong delivery may be the most practicable in some cases. Humidification may provide some benefit. Establish monitoring: ● 2. IV access: ● 3. HR, BP, RR, Temperature, pulse oximetry, conscious state, (drowsiness may precede respiratory arrest). IV access should be secured, (although this may not be appropriate in children in the first instance as distress with exacerbate an airway obstruction). Resuscitation cube: ● Patients should be closely monitored in an appropriate resuscitation cube that is stocked with resuscitation drugs and equipment. Intubation is likely to be difficult, and a surgical airway may be required. Equipment for this should be on hand. ● 4. Appropriately experienced staff should monitor the patient Specific treatments where applicable: Examples include: 5. ● Adrenaline nebulizers, for suspected or possible allergic reactions or for croup in children. ● IV antibiotics, for suspected infective causes. Referral: ● There must be early referral to Anaesthetics and/or ICU to assess the airway and manage it urgently should this become necessary. ● Other referrals may also be appropriate such as ENT or thoracic surgery Disposition This will obviously depend on the exact cause of the obstruction, how unstable the patient is and what management has already been initiated in the ED. In general terms however patients with stridor should be admitted to an ICU for close monitoring and to be in the best environment should urgent intervention become necessary. References 1. Stridor in Adults: Recommendations: Victorian Consultative Council on Anaesthetic Mortality and Morbidity (VCCAMM). February 6, 2006. Dr J. Hayes Dr J. Briedis, Director of Anaesthetics Reviewed 11 May 2009.