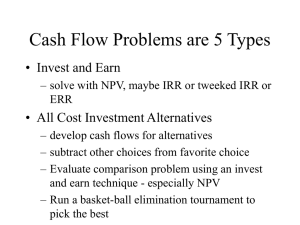

chapter organization

CHAPTER 9

MAKING CAPITAL INVESTMENT DECISIONS

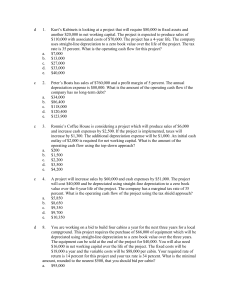

CHAPTER 9 QUIZ

CHAPTER ORGANIZATION

9.1

Project Cash Flows: A First Look

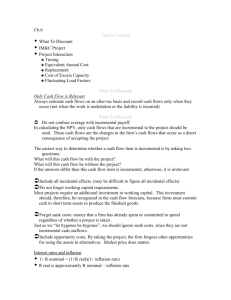

Relevant Cash Flows - cash flows that occur (or don’t occur) because a project is undertaken. Cash flows that will occur regardless of whether or not we accept a project aren’t relevant. o Incremental cash flows – Any and all changes in the firm’s future cash flows that are a direct consequence of taking the project. o The Stand-Alone Principle - Viewing projects as “mini-firms” with their own assets, revenues, and costs allows us to evaluate the investments separately from the other activities of the firm.

9.2

Incremental Cash Flows

Sunk Costs – A cash flow already paid or accrued. These costs should not be included in the incremental cash flows of a project. From an emotional standpoint, it does not matter what investment has already been made.

We need to make our decision based on future cash flows, even if it means abandoning a project that already represents a substantial investment.

Example: A soft-drink company has spent $1,000,000 on product testing, surveys, and development and is deciding whether or not to market a new soft drink. Should the $1,000,000 be included in the project cash flow estimates when making the decision?

Opportunity Costs - Any cash flow lost or foregone by taking one course of action rather than another. Applies to any asset or resource that has value if sold or leased rather than used.

Example: The soft-drink company mentioned above owns a factory that is not currently being used which can provide the manufacturing capacity for the new soft drink. The original cost of the factory was $7,000,000 and its current market value is $12,000,000. Alternatively, the factory could be leased to another firm for $500,000 per year. What are the relevant cash flows that should be considered when making the decision?

Prepared by Jim Keys 1

Side Effects - With multi-line firms, projects often affect one another – sometimes helping, sometimes hurting.

The point is to be aware of such effects in calculating incremental cash flows. Erosion – new project revenues gained at the expense of existing products or services.

Example: The projected sales for the new soft drink are $4,000,000 per year, although it is estimated that $750,000 of these sales are from current customers that will switch from one of the firm’s other soft drink flavors. What is the correct incremental revenue from the new soft drink that should be used in the capital budgeting decision?

Net Working Capital - New projects normally will require that the firm invest in net working capital in addition to long-term assets. They often require incremental investments in cash, inventories, and receivables that need to be included in the cash flow for the project if they are not offset by changes in payables (which they usually are not). Later, as projects end, this investment is often recovered.

Example: Undertaking the new soft drink project will require an additional investment in inventory of $1,500,000. Due to the increased level of sales, accounts receivable are expected to increase by $800,000 and the increase in accounts payable is projected to be $450,000 owing to the increased level of raw material purchases. How do these cash flow estimates affect the cash flow projections?

Financing Costs - We generally don’t include interest or principal payments on debt, dividends or other financing costs in computing cash flows. Financing costs are part of the division of cash flows from a project to providers of capital and are reflected in the discount rate used to discount the project cash flows.

Note: In finance, we separate the investment and financing decisions. A project’s cash flows are estimated regardless of how we plan to finance the project and the required rate of return (also referred to as the “cost of capital”). The investment and financing decisions are brought together when we apply a decision rule (NPV, IRR, etc.) and the associated required rate of return to our cash flow estimates.

Other Issues - Use cash flow, not accounting numbers. Use after-tax, not pretax, cash flows, (the tax bill is a cash outlay even though it is based on accounting numbers).

Note: Setting up timelines and performing calculations are typically the least burdensome portion of the task of capital budgeting. Rather, the difficulties arise principally in two areas: (1) generating good investment projects, and (2) developing reliable cash flow estimates for these projects. It should be pointed out that investing in fixed assets differs from investing in financial assets in at least one important sense. It is easy to find the investment opportunity set for financial assets and then perform an analysis to decide among the opportunities. Preparation of a capital budget, on the other hand, requires that people investigate and develop new project proposals, estimate the cash flows associated with these projects, and only then perform the analyses. Developing reliable cash flow estimates ranges from being a relatively minor task (say a simple replacement project) to one that is subject to a great deal of uncertainty. This requires all the analytical tools available as well as experience.

Prepared by Jim Keys 2

9.3

Pro Forma Financial Statements and Project Cash Flows

Getting Started: Pro Forma Financial Statements

Treat the project as a mini-firm:

1. Start with pro forma income statements (don’t include interest) and balance sheets. Note that the balance sheets are often foregone, and only the income statements are used. This is because the NWC requirements are often considered as a percent of sales, the major fixed asset requirements are the initial cost and salvage and financing costs aren’t considered in the cash flows.

2. Determine the sales projections, variable costs, fixed costs and capital requirements.

At this point, we need to start converting this accounting information into cash flows .

Project Cash Flows

Project cash flow = Project operating cash flow – Project change in NWC – Project capital spending o Operating cash flow = EBIT + Depreciation – Taxes o Operating cash flow = $33,000 + $30,000 - $11,220 = $51,780

Prepared by Jim Keys 3

o Project Net Working Capital and Capital Spending: We next need to take care of the fixed asset and net working capital requirements. The firm must spend $90,000 up front for fixed assets and invest an additional $20,000 in net working capital. The immediate outflow is thus $110,000. At the end of the project's life, the fixed assets will be worthless (the salvage value will be zero), but the firm will recover the $20,000 that was tied up in working capital. This will lead to a $20,000 cash inflow in the last year.

On a purely mechanical level, notice that whenever we have an investment in net working capital, that same investment has to be recovered; in other words, the same number needs to appear at some time in the future with the opposite sign.

Projected Total Cash Flow and Value

NPV

20%

$110,000

$51,780

(1.20)

1

$51,780

$71,780

(1.20)

2

(1.20)

3

$10,647.69

Therefore, since NPV is > 0, we should accept the project. o The project’s IRR = 25.76%. Since the IRR is > r (25.76% > 20%), we should accept the project. o Compute the project’s payback period (PB)

> o Compute the project’s modified internal rate of return (MIRR)

> o Compute the project’s profitability index (PI)

>

Capital spending at the time of project inception (i.e., the “initial outlay”) might include the following items:

+ purchase price of the new asset

- selling price of the asset replaced (if applicable)

+ costs of site preparation, setup and startup

+/- increase (decrease) in tax liability due to sale of old asset at other than book value

= net capital spending

The Tax Shield Approach

A useful variation on our basic definition of operating cash flow (OCF) is the tax shield approach. The tax shield definition of OCF is:

Prepared by Jim Keys 4

OCF* = [(Sales – Costs) x (1 – T )] + (Depreciation x T ), where T is the corporate tax rate.

*More specifically: OCF = [(ΔSales – ΔCosts) x (1 – T )] + [(ΔDepreciation) x ( T )]

Assuming that T = 34%, the OCF works out to be:

OCF = [($200,000 – $137,000) x (1 – .34)] + ($30,000 x .34)

OCF = ($63,000 x .66) + $10,200

OCF = $41,580 + $10,200

OCF = $51,780

This is just as we had before. This approach views OCF as having two components. The first part is what the project's cash flow would be if there were no depreciation expense. In this case, this would-have-been cash flow is $41,580.

The second part of OCF in this approach is the depreciation deduction multiplied by the tax rate. This is called the depreciation tax shield. We know that depreciation is a noncash expense. The only cash flow effect of deducting depreciation is to reduce our taxes, a benefit to us. At the current 34 percent corporate tax rate, every dollar in depreciation expense saves us 34 cents in taxes. So, in our example, the $30,000 depreciation deduction saves us

$30,000 × .34 = $10,200 in taxes. The tax shield approach will always give the same answer as our basic approach.

9.4

More on Project Cash Flow

A Closer Look at Net Working Capital

Accounts receivable and inventory increase to support higher sales levels. Accounts payable also tends to increase to support the higher inventory levels, however, the cash flows associated with these increases do not appear on the income statement when they occur. This is due to the matching principal, where the cost of inventory is not reflected until it is actually sold and revenue is recorded even though the cash has not been received if the goods or services were sold on credit. If the cash flows associated with these accounts aren’t on the income statement, they won’t be part of operating cash flow. So, similar to fixed assets, we have to consider changes in NWC separately.

Depreciation - Depreciation is a non-cash deduction. However, depreciation affects taxes, which are a cash flow. The relevant depreciation expense is the depreciation that will be claimed for tax purposes. Consequently, we need to understand how the IRS requires depreciation to be computed.

MACRS depreciation – most assets are required to be depreciated using MACRS ( M odified A ccelerated C ost

R ecovery S ystem). Each asset is assigned to a specific property class and depreciation is figured based on the percentages provided in Table 9.7. Note that assets are depreciated to zero and MACRS follows a mid-year convention. The mid-year convention causes depreciation expense to be taken in one more year than specified by the property class, i.e., 3-year MACRS has four years of depreciation.

Prepared by Jim Keys 5

MACRS Depreciation

The Staple Supply Co. has just purchased a new computerized information system with an installed cost of $160,000.

The computer is treated as five-year property. What are the yearly depreciation allowances? Based on historical experience, we think that the system will be worth only $10,000 when we get rid of it in four years. What are the tax consequences of the sale? What is the total aftertax cash flow from the sale?

The yearly depreciation allowances are calculated by just multiplying $160,000 by the five-year percentages in the table above:

Notice that we have also computed the book value of the system as of the end of each year. The book value at the end of Year 4 is $27,648. If we sell the system for $10,000 at that time, we will have a loss of $17,648 (the difference) for tax purposes. This loss, of course, is like depreciation because it isn't a cash expense.

What really happens? Two things. First: We get $10,000 from the buyer. Second: We save .34 × $17,648 = $6,000 in taxes. So, the total aftertax cash flow from the sale is a $16,000 cash inflow.

Prepared by Jim Keys 6

An Example: The Majestic Mulch and Compost Company (MMCC)

NPV

15%

$820,000

$107,169

(1.15)

1

$212,113

(1.15)

2

$250,673

(1.15)

3

$232,723

(1.15)

4

$214,040

(1.15)

5

$189,290

(1.15)

6

$156,920

(1.15)

7

$266,204

(1.15)

8

$65,725.63

Where do we go from here? If we have a great deal of confidence in our projections, then there is no further analysis to be done. We should begin production and marketing immediately. It is unlikely that this will be the case. It is important to remember that the result of our analysis is an estimate of NPV, and we will usually have less than complete confidence in our projections. This means we have more work to do. In particular, we will almost surely want to spend some time evaluating the quality of our estimates.

9.5

Evaluating NPV Estimates

The Basic Problem - Computing an NPV is putting a market value on uncertain future cash flows. Projecting the future involves the potential for error. Major error sources are biases and omissions. There are two main reasons for positive NPVs: (1) we have constructed a good project, or (2) we have done a bad job of estimating

NPV. Similarly, a negative computed NPV might be reflective of a bad project, or of a bad job of estimating

NPV. Estimated cash flows are expectations, or averages, of possible cash flows, not exact figures (although if an exact figure were available, you would use it).

Forecasting Risk - the danger of making a bad (value destroying) decision because of errors in projected cash flows. This risk is reduced if we systematically investigate common problem areas.

Prepared by Jim Keys 7

Sources of Value - The first and best guard against forecasting risk is to keep in mind that positive NPVs are economic rarities in competitive markets. In other words, for a project to have a positive NPV, it must have some competitive edge – be first, be best, be the only. Keep in mind the economic axiom that in a competitive market excess profits (the source of positive NPVs) are zero.

In “Corporate Strategy and the Capital Budgeting Decision” (Midland Corporate Finance Journal, Spring, 1985, pp. 22-

36), Alan Shapiro states that a firm’s capital budgeting program should “establish strategic options in order to gain competitive advantage.” Further, successful investments, according to Shapiro, are those investments “that involve creating, preserving, and even enhancing competitive advantages that serve as barriers to entry.” The following are project characteristics associated with positive NPVs.

1) Economies of scale

2) Product differentiation

3) Cost advantages

4) Access to distribution channels

5) Favorable government policy

Shapiro’s article serves both to take us past the standard number-crunching and to encourage us to think of capital budgeting from the strategic, or “big-picture” standpoint: how will this project (or group of projects) benefit the firm as a whole.

9.6

Scenario and Other What-If Analyses

Getting Started - What things are likely to be wrong and what will be the effect if they are? Start with a base case – the expected cash flows – then ask “what if …?”

Scenario Analysis

Worst-case/Best-case scenarios: putting lower and upper bounds on cash flows. Common exercises include poor revenues/high costs and high revenues/low costs. Note that a thorough scenario analysis starts with Basecase/Worst-case/Best-case and then expands from there.

If, under most circumstances, the discounted projected cash flows are sufficient to cover the outlay, we can have a high level of confidence that the NPV is positive. Beyond that, it is difficult to interpret the meaning of the scenarios.

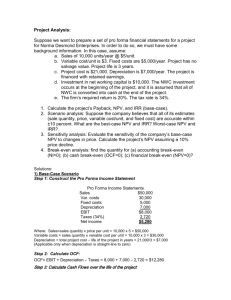

Example : The project under consideration costs $200,000, has a five-year life, and has no salvage value. Depreciation is straight-line to zero. The required return is 12 percent, and the tax rate is 34 percent.

Prepared by Jim Keys 8

Sensitivity Analysis

To conduct a sensitivity analysis, hold all projections constant except one; alter that one, and see how sensitive

NPV is to the change – the point is to get a fix on where forecasting risk may be especially severe. Common exercises include varying sales, variable costs and fixed costs.

Sensitivity analysis is a variation on scenario analysis that is useful in pinpointing the areas where forecasting risk is especially severe. The basic idea with a sensitivity analysis is to freeze all of the variables except one and then see how sensitive our estimate of NPV is to changes in that one variable. If our NPV estimate turns out to be very sensitive to relatively small changes in the projected value of some component of project cash flow, then the forecasting risk associated with that variable is high.

To illustrate how sensitivity analysis works, we go back to our base case for every item except unit sales. We can then calculate cash flow and NPV using the largest and smallest unit sales figures.

The results of our sensitivity analysis for unit sales can be illustrated graphically as in Figure 9.1. Here we place NPV on the vertical axis and unit sales on the horizontal axis. When we plot the combinations of unit sales versus NPV, we see that all possible combinations fall on a straight line. The steeper the resulting line is, the greater is the sensitivity of the estimated NPV to the projected value of the variable being investigated.

FIGURE 9.1 Sensitivity analysis for unit sales

Prepared by Jim Keys 9

By way of comparison, we now freeze everything except fixed costs and repeat the analysis:

What we see here is that, given our ranges, the estimated NPV of this project is more sensitive to projected unit sales than it is to projected fixed costs. In fact, under the worst case for fixed costs, the NPV is still positive.

As we have illustrated, sensitivity analysis is useful in pinpointing those variables that deserve the most attention. If we find that our estimated NPV is especially sensitive to a variable that is difficult to forecast (such as unit sales), then the degree of forecasting risk is high. We might decide that further market research would be a good idea in this case.

Because sensitivity analysis is a form of scenario analysis, it suffers from the same drawbacks. Sensitivity analysis is useful for pointing out where forecasting errors will do the most damage, but it does not tell us what to do about possible errors.

9.7

Additional Considerations in Capital Budgeting

Managerial Options and Capital Budgeting - The opportunity to change plans, dependent upon future events.

These options are valuable. Because they involve real (as opposed to financial) assets, such options are often called “real” options. o Contingency planning involves determining what will be done if this or that actually happens. This can be explored with “what if” analysis. o Option to expand (call option) - ignoring this option can result in underestimating the NPV because of the possibility of profitable “follow-on” projects. o Option to abandon (put option) - ignoring this option can result in underestimating NPV because the right to quit a loser is valuable. o Option to wait (call option) - waiting for favorable conditions or simply for some uncertainty to be resolved is a valuable option.

Strategic options are possible future investments that may result from an investment under consideration today.

Capital Rationing

Capital budgeting rules are distorted when soft or hard rationing occur. Soft rationing is self-imposed rationing, usually by top-level decision-makers within the firm. It often occurs for administrative reasons that have little or nothing to do with value maximization. The important thing about soft rationing is that the corporation as a whole isn't short of capital; more can be raised on ordinary terms if management so desires. Ongoing soft rationing means we are constantly bypassing positive NPV investments. This contradicts our goal of the firm.

Hard rationing , the lack of funds at any rate, is often associated with market imperfections or financial distress.

Prepared by Jim Keys 10