INITIAL ASSESSMENT OF ACUTELY SICK PATIENTS WITHIN

advertisement

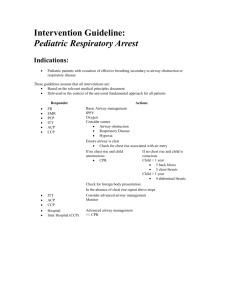

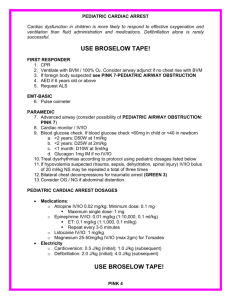

RECOGNITION & TREATMENT OF ACUTELY SICK PATIENTS WITHIN PRIMARY CARE TRUSTS Gayle Harris 1 Jan 2011 Research, as cited in the Resuscitation Council (UK) (2005) guidelines, has established that many cardiac arrests, deaths and unplanned admissions to intensive care are associated with the failure to establish appropriate and early preventative treatments. The Resuscitation Council (UK) (2010) guidelines re-emphasised how early detection of life threatening illness and initiation of prompt simple actions reduce complications and saves lives. It is recognised that the persons most likely to attempt resuscitation are general practitioners and nursing staff. However, any professional health care worker may contribute either directly or indirectly. Published evidence testifies to the effectiveness of resuscitation by general practitioners and primary care providers equipped with defibrillators. The Nottingham Primary Care Organisations have highlighted the need for staff to have access to information to address the above issues. The basis of this information package is drawn from scientific papers or reports published previously by the Resuscitation Council (UK), the Royal College of Anaesthetists, the British Heart Foundation, the British Medical Association and the ALERT course manual (2nd edition). Gayle Harris Interventions Facilitator Learning and Development Dept. Byron Court Brookfield Gardens Arnold Nottingham NG5 7EW Tel. 0115 8831811 e-mail-gayle.harris@nottspct.nhs.uk Gayle Harris 2 Jan 2011 Assessment of Critically Ill Patient When managing critically ill patients, or those at risk of life threatening illness, it is vital to undertake frequent reassessments. These are made easier if the assessment scheme is simplified and if every member of the healthcare team uses the same systematic approach, to reduce the likelihood of mistakes or misunderstanding. It also ensures that the whole team is working toward a ‘common goal’. The system described below is based on the practices of experienced clinicians and follows the basic structure of many of the life support courses currently in common use in the UK. The initial assessment system is directed at making the patient safe, rather than coming to a definite diagnosis. In assessing any patient, a simple question such as ‘How are you?’ can provide significant information. For example, a normal verbal response from the patient immediately informs you that the patient has a patent airway, is breathing and is supplying his/her brain with blood. Patients who can only speak in short sentences, or say one or two words at a time are usually in extreme respiratory distress and may be at risk of sudden respiratory arrest. Failure of the patient to respond is a very clear marker of serious illness. In keeping with other life support courses, the system we are using begins with the rapid detection and simultaneous treatment of potentially life-threatening emergencies. Consequently, it uses the familiar A-B-C-D-E system in which: A is for Airway B is for Breathing C is for Circulation D is for Disability (i.e. patients conscious level); and E stands for Exposure (permitting full patient examination) Assessment and actions are prioritised in this order because, in general, airway obstruction kills faster than disordered breathing, which in turn kills faster than haemorrhage or cardiac dysfunction. Gayle Harris 3 Jan 2011 A – AIRWAY Nasal septum Adenoids Tonsil Palate Tongue Epiglottis Larynx –‘voice box’ (shown in blue) Oesophagus (Food Pipe) Vocal cords Obstruction of the upper airway is a medical emergency. You should consider obtaining expert help immediately. The obstruction may be partial or complete, and may occur at any level of the respiratory tract from mouth to trachea. Common causes of airway obstruction are: Tongue Vomit, secretions, blood or fluid from the stomach Swelling due to trauma, allergy or infection Laryngeal oedema (swelling in voice box) due to burns, inflammation or allergy Laryngeal spasm (spasm in voice box) due to foreign body, airway irritation or secretions Tracheobronchial obstruction (windpipe/lungs) due to secretions, inhaled stomach contents, fluid with the lungs or irritation of the wind pipe. Recognition that airway obstruction is present is based on a simple ‘look, listen and feel’ approach: Gayle Harris 4 Jan 2011 Look For - Use of the accessory muscles of respiration (i.e. neck and shoulder muscles) Deviation of wind pipe at throat level (Adams apple) ‘See-saw’ pattern of breathing in which inspiration is accompanied by outward movement of the chest, but in-drawing of the abdomen and vice versa during expiration) Blue/purple colouring of skin is a late sign Listen In complete airway obstruction, there are no breath sounds at the mouth or nose. In partial obstruction, air entry is diminished and often noisy. Certain noises assist in localising the level of the obstruction:Gurgling - suggests the presence of liquid in the mouth or upper airway; Snoring - often caused by tongue and throat muscles losing tone; Stridor – noise is caused by obstruction above or at the level of the voice box; Wheeze – noise results from blocked airways during exhalation (e.g. Asthma). Feel A simple way of determining whether airway obstruction is present is to feel for the presence of air movement at the mouth by placing your face or hand immediately in front of the patient’s mouth. Emergency management of upper airway obstruction In the majority of cases within the Primary Care setting, the use of simple measures are all that is required to open the airway, such as the Head tilt/chin lift or jaw thrust manoeuvres. Jaw Thrust Head tilt/ chin lift Gayle Harris 5 Jan 2011 B – BREATHING Evidence of respiratory distress or inadequate ventilation can also be determined using a simple ‘look, listen and feel’ approach. Look Respiratory rate The depth of each breath Effort or work of breathing Agitation, confusion or reduced conscious levels Use of abdominal muscles to aid breathing Both sides of chest moving together. Sweating Listen To the patients breathing a short distance from his/her face. Rattling airway noises indicate the presence of secretions, usually due to the patient being unable to cough sufficiently or to take a deep breath. Stridor or wheeze suggests partial, but significant, airway obstruction. Feel The position of the wind pipe should be assessed for deviation which may indicate air in the chest causing a collapsed lung (pneumothorax). Assess the depth and equality of movement on each side of the chest. Emergency management of breathing disorders These should be treated urgently and before progressing to any further patient assessment. If mouth-to-mouth/mask is not working – check neck for tracheotomy or laryngectomy stoma. All critically ill patients should receive oxygen in order to prevent organ damage or cardiac arrest. For most patients this may be safely achieved by sitting the patient up and administering high flow oxygen (12-15litres/min) via an oxygen mask with an oxygen reservoir bag (non re-breath mask). Oxygen therapy should always be prescribed, except in an emergency when it may be acceptable to get a doctor’s verbal Gayle Harris 6 Jan 2011 prescription in order that treatment can commence whilst medical emergency services are on their way to the patient. In a subgroup of patients suffering from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), high concentrations of oxygen may have disadvantages and some limitations in therapy may be warranted. Nevertheless, this latter group of patients will also suffer organ damage or cardiac arrest, if their blood oxygen levels are allowed to fall. Always monitor the effects of the oxygen therapy. This can be done clinically by observing the patient’s colour, degree of respiratory distress and respiratory rate. C – CIRCULATION Look For signs of shock – pale, cold, clammy or sweating Capillary refill (normally less than 2 seconds) can be quickly assessed by applying pressure for 5 seconds to a fingertip nail, held at heart level, and counting the time it takes for capillary refill after the pressure has been released. Peripheral cyanosis (blue/grey tinge to skin) Reduced level of consciousness Examination should include search for obvious external haemorrhage. Listen A patient’s blood pressure may be entirely normal, despite the presence of shock due to the body’s ability to compensate, so careful assessment of other symptoms must be made. Feel assessment of the circulation should include monitoring the pulse, assessing for its presence, rate quality, regularity and equality. A thready pulse suggests a poor cardiac output, whilst a bounding pulse may indicate sepsis. Emergency management of circulatory disorders During initial assessment it is vital to seek out the signs that indicate immediately lifethreatening conditions, e.g. massive or continuing bleeding, constricting chest pain or grey, cold and sweaty to touch. Insertion of a cannular at the earliest time for fluid and drug administration should be attempted and medical emergency services should be alerted promptly. Gayle Harris 7 Jan 2011 D – DISABILITY A Alert V Responds to Voice P Responds to Pain U Unresponsive A rapid assessment of the patient’s conscious level should be performed using the ‘AVPU’ system. Where possible note pupil size, equality and reaction to light and test blood sugar level if possible to establish or eliminate as a cause of collapse. Patients with adequate spontaneous breathing and circulation who are unconscious are at risk of developing airway obstruction if lying in their backs. In addition, airway protective reflexes may be insufficient to prevent inhalation of secretions, vomit or blood. Consequently, unconscious patients are best nursed in the lateral ‘recovery’ position, with consideration to those patients with or suspected of having back or neck injury. E – EXPOSURE In order that patients are examined properly, and details are not missed, full exposure of the body may be necessary. However, this should be done in a way that respects the dignity of the patient and prevents heat loss. At this stage the examination should be focused on the most likely area of the body causing the patient’s poor condition (e.g. bleeding point, where trauma has occurred). Do You Need Help? You should have considered whether you need help, maybe because the situation is one with which you are unfamiliar, because specialist skills are required or merely because you need ‘another pair of hands’. Emergency services must be sought at the earliest possible time if the airway, breathing or circulation has been compromised and intervention required, during the A.B.C.D.E assessment. Gayle Harris 8 Jan 2011 Useful questions that may be asked when following the A.B.C.D.E assessment AIRWAY: Is it noisy? - What kind of noise can you hear? Is it silent? BREATHING: Is it too fast or too slow? Can the patient talk normally? Is there increased effort to breath? Does the patient have a blue/grey tinge around lips? CIRCULATION: Is the patient cold and pale? Is the patient sweaty? Does the Patient have Chest Pain? Is the patient nauseated or vomiting? Is there evident blood loss DISABILITY: Assess patients conscious level with:A – Alert V – Voice P – Pain U – Unresponsive Observe Pupil size and reaction to light Check blood sugar level-Bm (if equipment available) EXPOSURE: Note any Fitting/seizure Does Patient have a rash, bleeding or wound? Look for indications of cause of collapse TREAT COMPLICATIONS AS YOU FIND THEM. DO NOT DELAY CALL FOR EMERGENCY SERVICES IF COMPLICATIONS FOUND. Gayle Harris 9 Jan 2011 Initial Responder Recognition and Treatment of Heart Attack(Acute Coronary Syndrome) It is essential that all staff within Primary Care are able to recognise the symptoms that may indicate the patient is having a Heart Attack, and be able to treat them promptly to reduce heart muscle damage due to lack of oxygen and in some patient’s, prevent cardiac arrest. This may simply be recognising the need for an immediate call for emergency services. Recognising patients with symptoms suggesting ‘Heart Attack’ Signs and Symptoms The patient may present with one or more of the following, Tightness/ache across the chest Radiating to pain o Throat/arms/back/epigastrium (central upper part of the abdomen) Profuse sweating Nausea/vomiting Breathlessness/Pale, grey or blue lips &/or skin A history of severe or un-resolving angina may be given by the patient alongside these symptoms, but without a 12 lead ECG and blood test it is impossible to know how much damage has or is occurring to the heart muscle. All patients are therefore treated as high risk until symptoms subside or emergency medical services arrive with more advanced monitoring. Patients whose symptoms do not subside quickly, but do not proceed into cardiac arrest may be treated with the aim to reduce heart muscle damage due to lack of oxygen to heart muscle, with the administration of ‘M.O.N.A’. NB. Do not delay calling emergency services to administer M.O.N.A. M – Morphine (or diamorphine) (5-10mg) O – Oxygen (12-15 l/min) N – Nitro-glycerine (GTN spray or tablet) A – Aspirin 300mg orally (crush/chew) Gayle Harris 10 Jan 2011 Pain will increase oxygen demand, so by reducing the pain with drugs like morphine and giving high concentration oxygen via a non re-breath mask, a patient might quickly have improved oxygen supply to the heart muscle. Give morphine (diamorphine) slowly and at intervals so as not to induce respiratory compromise. Nitro-glycerine (GTN) will widen (dilate) blood vessels; consideration must therefore be given to the effects of blood vessels widening on patients not accustomed to this medication – dizziness, faint, collapse. Aspirin may prevent blood clot formation, and even begin to break down existing clot/s. It might be advisable to ask patients if they know any reason which may prevent them taking it, (e.g. Asthma, ‘Stroke’, or Gastric complications). The Chain Of Survival The Chain of Survival is only as strong as its weakest link. Early access to emergency services, drugs and equipment will significantly increase the patient’s chances of survival. Start cardiopulmonary resuscitation to ‘sustain’ the patient until emergency services arrive. Commencement of basic life support should not delay delivery of shocks, if Automated External Defibrillation is immediately available that will take precedence. (Defibrillation is a treatment; basic life support is a holding mechanism). The final link in the chain is to stabilise the patient, and transfer to an intensive care unit for advanced life support treatment and investigation of underlying cause of cardiac arrest. Gayle Harris 11 Jan 2011 In Summary Patients presenting with acute illness at any Primary Care Trust will undergo initial assessment using the A.B.C.D.E. approach. Each stage should be assessed and treatment provided prior to moving on, (i.e. the airway must be clear and open before breathing can be assessed). Those patients with signs and symptoms of severe or un-resolving angina may also be treated with M.O.N.A., (if available and no contra-indications are found), to reduce muscle damage due to lack of oxygen and in some cases prevent deterioration into cardiac arrest. In cardiac arrest the use of the ‘Chain of Survival’ may be utilised as a reminder of action and services to be notified. Gayle Harris 12 Jan 2011 QUESTIONS 1. What systematic approach is used for rapid detection and treatment of potentially life-threatening emergencies? 2. What symptoms may indicate a complication or obstruction of the upper airway? 3. Rapid assessment of conscious level can be performed using what method? 4. Oxygen administration in the critically sick person can prevent cardiac arrest; discuss how, when and by whom it may be given, and any considerations that need to be taken into account. 5. What signs and symptoms might indicate difficulty breathing? Gayle Harris 13 Jan 2011 6 Vital signs should be monitored whilst carrying out the ABCDE assessment. Indicate which vital sign should be monitored at each stage of the process. A– B– C– D– E- 7. How do the symptoms associated with unstable angina differ from those of stable angina? 8. “The Chain of survival is only as strong as its weakest link” Discuss the meaning of this statement. Gayle Harris 14 Jan 2011