Psy 121

advertisement

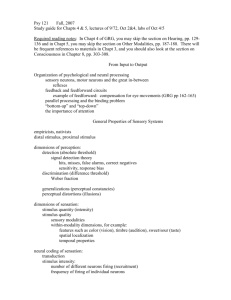

Psy 121 Fall, 2007 Study Guide for lecture and assigned readings for Sept 4 Appended please find a summary/clarification of the argument for functional modularity of face recognition processing. Outline of topics for lecture & readings Tues, Sept 4 Today, we will consider the judgments of current state, such as affective state, direction of attention/interest that can be “read” from faces. In order to consider the topic of facial expressions of affect/emotion, we’ll first briefly review current thinking on the topic of what emotions are. AFFECTS Some definitions Affect Mood: unattributed core affect Emotions: intentional states Dimensions of core affect James Russell, Lisa Feldman Barrett Arousal: evaluation of need for action (mental or physical) Valence: evaluation of hedonic value (pos/neg, approach/avoid) The emotions circumplex (GRG: Fig 12.9) Appraisal dimensions e.g., Roseman The role of emotion categories/labels (Feldman Barrett) Are there “basic” emotions? Possible criteria Shaver et al.’s data (GRG: Fig 12.8) Components of affective states: Cognitions “cold cognitions”: perception “hot cognitions”: evaluation (core affect) and appraisals Physiology Autonomic nervous system Patterns of brain activation (Richard Davidson, GRG: p. 472) Behavior, including approach/avoidance, facial expressions Subjective experience Temporal issues: cause and effect, dynamics GRG: Figs 12.4 – 12.6 What William James did not say (James-Lange theory, Ellsworth) Psy 121 Study Guide Sept 4, 2007 2 Affects as information Attribution of core affect: Murphy & Zajonc, Schachter & Singer Positive affects as “safety signals” e.g., Fredrickson. Isen GRG: p. 472, exs in Grewal & Salovey heuristic processing, creativity, broaden-and-build Gut feelings e.g., Damasio, the gambling task GRG: pp. 96-97, Grewal & Salovey Self-regulation Gross, Ochsner & Gross Reappraisal & suppression GRG: pp. 473-474 Developmental GRG p. 416 Individual differences Temperament Interoception (e.g., Craig) Emotion differentiation (Feldman Barrett, described in Grewal & Salovey) Emotional intelligence? (Grewal & Salovey) Functions of affects see GRG pp. 472-473 FACIAL EXPRESSIONS Fundamental question: to what extent are facial expressions “read outs” of affective state and to what extent are they social signals (involuntary and voluntary)? Paul Ekman and the neurocultural theory of universal facial expressions Especially important facial muscles: zygomatic and corrugator Voluntary and involuntary expressions Evidence for facial affect programs (i.e., the “neuro” part) A note about Darwin’s position Facial expressions in infants and the blind Messinger, Galati et al., GRG pp. 415, 467 Infant perception of facial expressions: GRG p. 398 Comparative studies Parr et al., GRG p. 467 Cross-cultural identification studies Ekman, Russell, GRG pp. 467-468 Critiques of these studies Microexpressions & the Diogenes project (New Yorker article) “reliable muscles,” e.g., Obicularis oculi, pars lateralis Evidence for the effects of experience and culture Display rules, decoding rules, “dialect theory” Ekman, Elfenbein & Ambady, GRG pp. 468-469 Cross-cultural differences Pollak et al. (described in Grewal & Salovey) Contextual factors The presence of an observer GRG p. 468-469 The influence of gaze direction (e.g., Adams & Kleck) Psy 121 Study Guide Sept 4, 2007 3 Gender effects GRG p. 469 Signals to others and signals to the self Emotion contagion, mimicry (e.g., Dimberg et al.) Mimicry in infants GRG pp. 372-373 Empathy Facial feedback hypothesis Mobius syndrome Study Guide for Grewal & Salovey The assigned article by Grewal & Salovey provides summaries of a number of current, important projects in the area of emotions research, for example: 1, Damasio’s research on the gambling task (advantageous decision-making) 2. Pollak’s research on the effects of abusive child-rearing on the perception of facial expressions 3. Isen’s work on the influence of positive emotions on creativity 4. Studies by Feldman Barrett and by Gross on managing emotions, the former of which includes an assessment of understanding emotions The point of these descriptions seems to be to convince us that the skills identified in the four-branch model exist and (for some of the described cases) are capable of varying. But, as Grewal & Salovey understand, the critical step is to convince us that these skills predict something interesting about our lives – and, specifically, something that is NOT predicted by general personality factors. Are you convinced? Painful though it may be, we should spend a few minutes trying to understand Figure 9. What should we be looking for in this Figure? Two clarifications: First, the correlations in the top half of the Figure are for pairs of the tests taken by a large sample of folks, the correlations in the bottom half are for tests “taken by” a small number of emotions experts. Second, the black and dark gray boxes on the left side and on the top of the correlation table should be “parsed” in the same fashion. The parsing on the left side is in error. For more information: Mayer’s web site: http://www.unh.edu/emotional_intelligence/index.html Psy 121 Study Guide Sept 4, 2007 4 Suggested readings Adams. R.B. & Kleck, R.E. (2005). Effects of direct and averted gaze on the perception of facially communicated emotion, Emotion, 5, 3-11. Craig, A.D. (2004). Human feelings: why are some more aware than others? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(6), 239-241. Davidson, R.J. (2000). Affective style, psychopathology, and resilience: Brain mechanisms and plasticity, American Psychologist, 11, 1196-1214. Dimberg, U., Thunberg, M. & Elmehed, K. (2000). Unconscious facial reactions to emotional facial expressions, Psychological Science, 11, 86-89. Ellsworth, P.C. (1994). William James and emotion: is a century of fame worth a century of misunderstanding? Psychological Review, 101(2), 222-229. Feldman Barrett, L., Lindquist, K.A. & Gendron, M. (2007). Language as a context for the perception of emotion, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(8), 327-332. Feldman Barrett, L., Mesquita, B., Ochsner, K. & Gross, J.J. (2007). The experience of emotion, Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 373-403. Frederickson, B.L. (2003). The value of positive emotions, American Scientist, 91, 330335. Ekman, P. (1993). Facial expressions and emotion, American Psychologist, 48, 384392. Elfenbein, H.A. & Ambady, N. (2003). Universals and cultural differences in recognizing emotions, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 159-164. Galati, D. Scherer, K.R. & Ricci-Bitti, P.E. (1997) Voluntary facial expression of emotion: comparing congenitally blind with normally sighted encoders, Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 73(6), 1363-1379. Goldman, A.I., Sripada, C.S. (2005). Simulationist models of face-based emotion recognition, Cognition, 94, 193-213. Gross, J.J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review, Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271-299. Messinger, D.S. (2002). Positive and negative: Infant facial expressions and emotions, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 1-6. Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). Embodying emotion, Science, 316, 1002-1005. Ochsner, K. & Gross, J.J. (2005). The cognitive control of emotion, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 242-249. Parr, L, Waller, B.M.& Vick, S.J. (2007). New development in understanding emotional facial signals in chimpanzees, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(3), 117-122. Roseman, I.J. (1991). Appraisal determinants of discrete emotions, Cognition & Emotion, 5(3), 161-200. Russell, J.A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion, Psychological Review, 110(1), 145-172. Russell, J. A., Bachorowski, J.-A. & Fernandez-Dols, J.-M. (2003). Facial and vocal expressions of emotion, Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 329-349. de Vignemont, F. & Singer, T. (2006). The empathic brain: how, when and why? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(10), 435-441. Psy 121 Study Guide Sept 4, 2007 5 Functional modularity of face recognition processing 1. Face processing for recognition depends primarily on the processing of the configuration of features of the face rather than on the processing of individual features. (Multiple examples of this were provided in Tues/Wed labs and Thurs lecture.) Indeed, the evidence suggests that this characteristic of face processing distinguishes it from the processing of other classes of objects that contain multiple exemplars (e.g., birds, cars, houses). 2. Prosopagnosia is a neuropsychological disorder in which there is a deficit in explicit face recognition in the absence of a deficit in the recognition of other objects (object agnosia). Prosopagnosics can recognize individuals based on their voices, and on distinctive facial features (such as a bushy beard or particular hairstyle), but seem to be unable consciously to access face identity in the normal (configuration-based) way. There are also a small number of object agnosics who retain the ability to recognize faces. This double dissociation between agnosia for faces and for objects suggests that at least some aspects of object and face recognition are functionally separate. 3. Some prosopagnosics demonstrate an ability to recognize previously-welllearned faces outside awareness (i.e., implicit recognition), as shown by the example provided in the video (using skin conductance responses as the indicator of recognition). However, studies of new face learning demonstrate a variety of deficits, even with measures of implicit recognition. N.B. This distinction between explicit (conscious, accessible to awareness) and implicit (occurring outside of awareness) processing will re-appear throughout the semester. Other examples of implicit processing were provided in last Tues/Wed’s labs.) 4. Are faces special because of their reliance on configural processing (a type of process-modularity that might reflect expertise) or because of the fact that they are faces per se (i.e., domain-specific modularity)? A set of abstract stimuli called Greebles has been developed for which investigators agree configural processing is required for recognition. In a recent study, a congenital prosopagnosic performed as well as non-prosopagnosic controls in a Greeble learning and recognition task. This finding strongly suggests that face processing shows domain-specific modularity.