Pragmatics

advertisement

Malamud

Intro to Linguistics

Fall 2007

Lectures on pragmatics: acting with speech

Pragmatics studies the aspects of meaning not accounted for by compositional semantics.

J.L. Austin, How to do things with words: people use language to accomplish certain kinds of acts,

broadly known as speech acts, and distinct from physical acts like drinking a glass of water, or mental

acts like thinking about drinking a glass of water.

Speech acts include asking for a glass of water, promising to drink a glass of water, threatening to drink a

glass of water, ordering someone to drink a glass of water, and so on.

- most of these ought really to be called "communicative acts", since speech not strictly required.

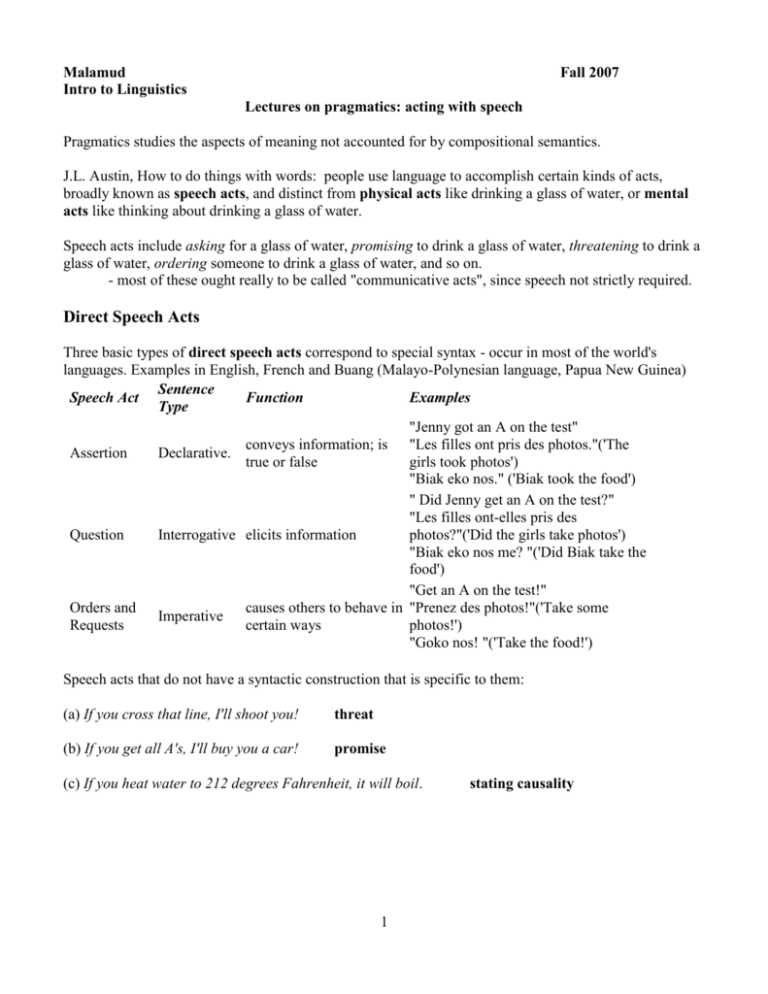

Direct Speech Acts

Three basic types of direct speech acts correspond to special syntax - occur in most of the world's

languages. Examples in English, French and Buang (Malayo-Polynesian language, Papua New Guinea)

Sentence

Speech Act

Function

Examples

Type

"Jenny got an A on the test"

conveys information; is "Les filles ont pris des photos."('The

Assertion

Declarative.

true or false

girls took photos')

"Biak eko nos." ('Biak took the food')

" Did Jenny get an A on the test?"

"Les filles ont-elles pris des

Question

Interrogative elicits information

photos?"('Did the girls take photos')

"Biak eko nos me? "('Did Biak take the

food')

"Get an A on the test!"

Orders and

causes others to behave in "Prenez des photos!"('Take some

Imperative

Requests

certain ways

photos!')

"Goko nos! "('Take the food!')

Speech acts that do not have a syntactic construction that is specific to them:

(a) If you cross that line, I'll shoot you!

threat

(b) If you get all A's, I'll buy you a car!

promise

(c) If you heat water to 212 degrees Fahrenheit, it will boil.

1

stating causality

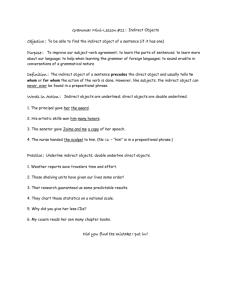

Indirect Speech Acts

Let's look again at the interrogative sentence:

(d1) Did Jenny get an A on the test?

direct question

(d2) Do you know if Jenny got an A on the test?

indirect question

The reply is directed to the speech act meaning, not the literal meaning.

Other indirect ways of asking the same question, using the declarative form:

(d3) I'd like to know if Jenny got an A on the test.

(d4) I wonder whether Jenny got an A on the test.

indirect question

indirect question

In the case of the speech act of requesting or ordering, speakers can be even more indirect:

(e1)( Please) close the window.

direct request

Conventional indirect requests may be expressed as questions as in (e2) and (e3): or as assertions (e4). In

context, (e5) and (e6) may also be immediately understood as a complaints, meant as an indirect request

for action.

(e2) Could you close the window?

indirect request

(e3) Would you mind closing the window? indirect request

(e4) I would like you to close the window. indirect request

(e5) The window is still open!

complaint / indirect request

(e6) I must have asked you a hundred times to keep that window closed! complaint/

indirect request

Felicity Conditions

In order to "do things with words", certain things must be true of the context in which speech acts are

uttered. In other words, a sentence must not only be grammatical (and not only make sense) to be

correctly performed, it must also be felicitous.

Three types of felicity conditions:

Preparatory conditions: the person performing the speech act has the authority to do so

the participants are in the correct state to have that act performed on them,

etc.:

(f) I now pronounce you man and wife.

Conditions on the manner of execution of the speech act,

e.g. touching the new knight on both shoulders with the flat blade of a sword (g) or

pointing in the appropriate direction (h):

(g) I hereby dub thee Sir Galahad.

(h) He went thataway!

2

Sincerity conditions are obviously necessary in the case of verbs like apologize and promise. That is, you

have to mean it, or at least be pretending that mean it, in order for an utterance involving such verbs to be

felicitous.

Some of the felicity conditions on questions and requests as speech acts can be described as follows,

where "S" = speaker; "H" = hearer; "P" = some state of affairs; and "A" = some action.

A. S questions H about P.

1. S does not know the truth about P.

2. S wants to know the truth about P.

3. S believes that H may be able to supply the information about P that S wants.

B. S orders H to do A (or requests that he do it).

1.

2.

3.

4.

S believes A has not yet been done.

S believes that H is able to do A.

S believes that H is willing to do A-type things for S.

S wants A to be done.

We can see what happens when some of these conditions are absent. In classrooms, for example, one

reason that children may resent teachers' questions is that they know that there is a violation of A.1: the

teacher already knows the answer. And a violation of B.2 can turn a request into a joke: "Would you

please tell it to stop raining?"

Gricean Conversational Maxims

The work of H.P. Grice takes pragmatics farther than the study of speech acts. Grice's aim was to

understand how "speaker's meaning" -- what someone uses an utterance to mean -- arises from "sentence

meaning" -- the literal (form and) meaning of an utterance.

Grice: many aspects of "speaker's meaning" result from the assumption that the participants in a

conversation expect each other to be cooperating:

He called this the Cooperative Principle. It has four sub-parts or maxims that cooperative

conversationalists assume each other to be respecting:

(1) The maxim of quality. Speakers' contributions ought to be true.

(2) The maxim of quantity. Speakers' contributions should be as informative as required; not saying

either too little or too much.

(3) The maxim of relevance. Contributions should relate to the purposes of the exchange.

(4) The maxim of manner. Contributions should be perspicuous -- in particular, they should be orderly

and brief, avoiding obscurity and ambiguity.

3

Grice was not acting as a prescriptivist when he enunciated these maxims, even though they may sound

prescriptive. Rather, he was using observations of the difference between "what is said" and "what is

meant" to show that people actually do follow these maxims in conversation.

E.g., the maxim of quantity (and quality) is at work in the following made-up exchange:

Parent: Did you finish your homework?

Child: I finished my algebra.

Parent: Well, get busy and finish your English, too!

Child did not say “I did not finish English” – but saying algebra specifically means that the child cannot

truthfully say more, and so is providing as much information as possible. So, the conclusion is warranted.

Similarly, below, you would be justified in assuming the person's other leg was bad, even though nothing

had been said about it at all, because otherwise the statement would violate the Maxim of relevance

(mentioning good must be relevant)

John has one good leg.

As another example, below, the hearer assumes that the speaker is observing the Maxim of quantity, so

that if the speaker didn't say the stronger statement, namely "Noone showed up", it's because the stronger

one isn't true. So, the hearer can safely assume that someone did show up.

A: How was the party?

B: Not everyone showed up

The maxim of relevance is behind the suspicious implications of this letter of recommendation (a classic

example).

Dear Admissions Committee:

I am pleased to recommend Pat Smith for admission to your program. He consistently

arrives on time, and is always appropriately dressed.

Sincerely,

Professor N.O. Wunn

The person reading this letter assumes that all the relevant information will be included; so the maxims

of quantity and relevance lead one to suspect that this is the best that the professor can say.

The main work of the Cooperative Principle is done when particular non-literal meanings are

conveyed by speakers violating in an obvious way, or "flouting" these maxims.

Irony and sarcasm:

Kim says "Oh, lovely!" when she sees dog crap on her carpet

4

Maxim of quality

“Lovely weather”

under torrential rain

Metaphorical speech:

She is our little flower

Indirect speech acts:

Can you pass me the salt?

Maxims of quality and relevance

Maxim of Relevance - the speaker clearly knows the answer is yes!

So, something else must have been meant – indirect request.

Flouting the maxim of relevance is a good way to say, indirectly, that you don't want to talk about

something.

Pat:

How's your work coming along?

Chris:

It sure is sunny outside.

The "be orderly" aspect of the maxim of manner is what causes us to interpret the following sentences

differently, even though, in a literal sense, they convey the same information.

a.

Joe and Sue got married and had a baby.

b.

Bill and Sally had a baby and got married.

The felicitous ordering reports the events in the same order in which they occurred, unless there's some

explicit indication of a difference, such as Bill and Sally had a baby after they got married.

5