Eureka, a Sneaker! - The Benjamin School

advertisement

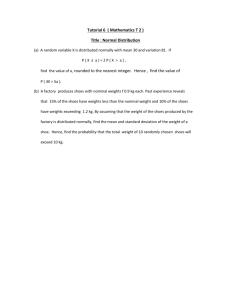

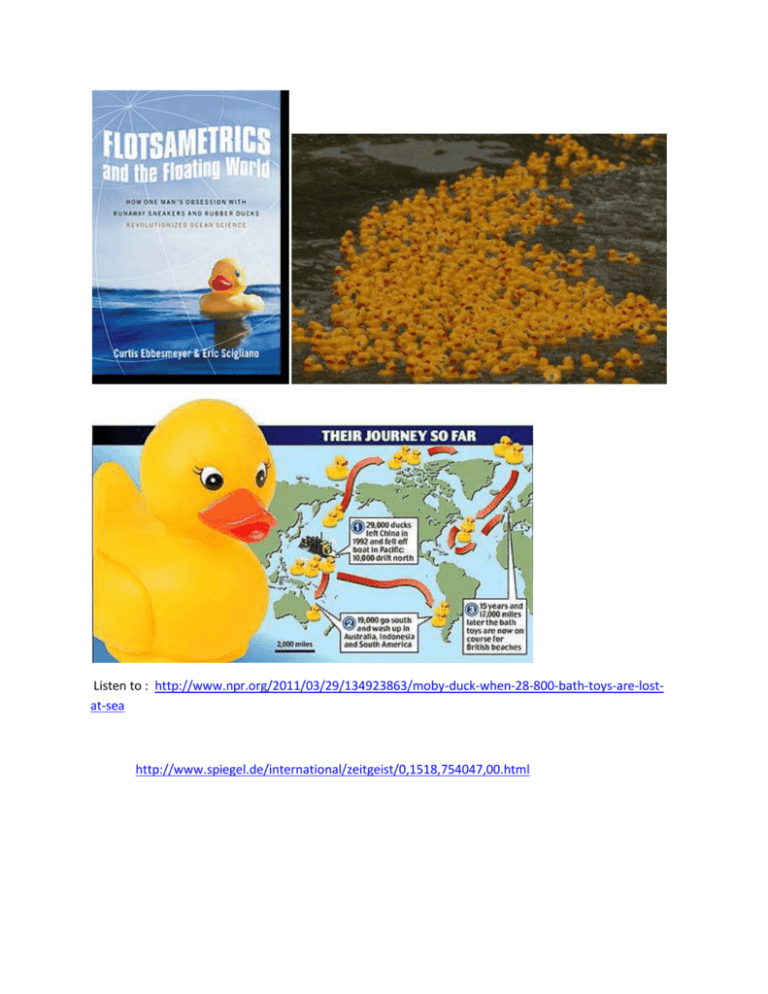

Listen to : http://www.npr.org/2011/03/29/134923863/moby-duck-when-28-800-bath-toys-are-lostat-sea http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/0,1518,754047,00.html Flotsametrics and the Floating World: An Excerpt Eureka, a Sneaker! “The ocean is forever asking questions and writing them aloud on the shore.” —Edwin Arlington Robinson, Roman Bartholow The year 1990 was a watershed year for me, and for flotsam science. No sooner had I decided to cut back on consulting work and concentrate on my own research than the other shoe dropped— literally. On May 27, 1990, the cargo vessel Hansa Carrier, en route from Korea to Los Angeles, hit a severe, sudden storm. Stowing cargo is critical on today’s ships, whose decks are packed up to seventy feet high with eight-by-ten-by-forty-foot steel shipping containers. Distribute the weight unevenly and the ship may heel over in a storm. Lash it too loosely and she may shed containers like a dog shaking off fleas. Cargo practices have since improved, but in the 1990s as many as ten thousand containers may have gone overboard each year. The largest known spill, during a 1998 typhoon, dropped three to four hundred containers into the mid-Pacific. The Hansa Carrier was named after the Hanseatic League, a medieval German merchant alliance with a famous seafaring history. But the ship’s reputation was less illustrious; her crew was notorious for stowing containers sloppily, so much so that some of the shippers who’d used her called her “the ship from hell.” When the May 27 storm hit, she lost twenty-one containers. Five were crammed with Nike shoes—eighty thousand sneakers, hiking boots, and children’s shoes. The pairs were unlaced, so each shoe became a separate item of flotsam. As usual, the shipping industry guarded the news closely; shippers and manufacturers tend to keep their cargo spills secret, to avoid embarrassment and liability. But then the shoes themselves blew the cover off. Eight months later, in January 1991, after drifting two thousand miles eastward, the Nikes began beaching on Vancouver Island. The prevailing winter winds and currents then pushed them north as far as the Queen Charlotte Islands. Then the winds shifted, as they do each spring, and blew south through the summer. Thousands of shoes stranded along the Oregon coast, just a few score miles from Nike’s headquarters outside Portland. The news media loved the story. One day, when I stopped by my parents’ house for our usual lunch of creamed eggs on toast, my mother pulled out the newspaper story she’d clipped on the Oregon shoe strandings, and I said I’d look into it. The floating world had given me the call. To the ancient Greeks, Nike was the winged goddess of victory, though it was another god, Hermes, who lent the hero Perseus the winged shoes that let him fly like a bird. In the late twentieth century, “Nikes” became first guided missiles, then sneakers. To me, they represented a chance to have a little fun with ocean currents, and a welcome respite from sewage, oil spills, and offshore platform designs. Drift of the great Nike sneaker spill of May 27, 1990, as simulated by OSCURS. N marks the spill site, the stippled plume indicates the drift path, and the dots at upper right show dates and locations where thirteen thousand shoes were discovered by beachcombers. At Station Papa, indicated by P, oceanographers released 33,869 message bottles during the International Geophysical Year. Click to see larger image Like an oceanic gumshoe, I set about tracking down the beached sneakers. When I ask shippers about flotsam washing up from their container spills, 95 percent stonewall. “We are not aware of any lost merchandise,” goes the standard answer. I could never find out what was in the other sixteen containers that washed off the Hansa Carrier that day. But Nike’s transportation department was refreshingly open about this spill. Its staff provided the date, latitude, and longitude and their container load plan, listing each container’s contents down to the last shoe. Unlike many other footwear manufacturers, Nike stamps a simple identification number, a “purchase order ID” (POID), on each of its shoes. It tracks its products so meticulously that it can trace a single shoe to its mother container. For example, the POID on a three-year-old Nike recovered on Maui, 90 04 06 ST, indicated that the Korean factory (ST) had received the order in April (04) for delivery by June (06) 1990. Following the POID s would eventually enable us to answer the question I’m always asked when I speak on the Great Sneaker Spill: How many of the five Nike containers broke open in the storm and disgorged their contents? We’ve found hundreds of shoes from each of four containers and not one shoe from the fifth. Someday, somewhere on the Pacific seabed, submarine archeologists will find sixteen thousand sneakers nestled in a giant steel shoebox. With the information Nike provided, we could determine conclusively whether any shoe that washed up had fallen off the Hansa. The first beachcombers’ reports of sneakers washing up— “forerunners,” as one reporter called them—were equally specific. I had something that’s very rare with spontaneous flotsam (as opposed to determinate drift markers): both point A, when and where an object starts to drift, and point B, when and where it washes up. With this data in hand, I thought of OSCURS, the Ocean Surface Current Simulator program that Jim Ingraham had developed at NOAA to calculate the effects of ocean currents on salmon migration. I wondered if OSCURS would work as well with inanimate drifters as it did with swimming fish; subtract the fish’s swim speed and you should have flotsam. In the decades since grad school, Jim and I had gone our separate ways, but the sneaker spill rekindled our friendship. I called him, and he was glad to help. I decided to stage a blind test of OSCURS. I gave Jim only point A, the Hansa spill, and asked if he could calculate point B, when and where the shoes would wash up. “I’ll fax back the answer in an hour,” he replied. OSCURS homed in like a carrier pigeon, making direct hits on the earliest point Bs—November and December 1990 on the Washington coast and January and February 1991 on Vancouver Island—where the first sneakers washed up. Jim and I needed more data—the dates and locations of other wash-ups. We began seeking out beachcombers in Oregon and asking if they’d spotted any Nikes, but it was a slow, laborious process. Then we hit the jackpot: One beachcomber directed me to Steve McLeod, a painter in the easygoing resort town of Cannon Beach. Steve is a classic starving artist; he’d won some recognition and big commissions but refused to play the corporate game, preferring to follow his muse and eke out what living he could. He’s also a dedicated beachcomber, which may nurture his muse and certainly boosted his living on this occasion. Twenty years earlier, as if by premonition, Steve had painted a picture of two gigantic hiking boots hovering over an imaginary beach. When he started finding beached Nikes, a light went on. This was the heyday of sneaker chic, when newspapers feasted on stories about inner-city kids shooting each other for their Air Jordans. Scrape off the barnacles, toss the washed-up Nikes in the washer, add a little bleach, and they looked and felt like new. Steve became a mail-order matchmaker for hundreds of people up and down the coast who’d found mismatched sneakers and wanted mates. He negotiated swaps: a size 10 left for a size 9 right here, a right size 12 for a left size 7 there. Soon everyone wound up with matched pairs, and Steve wound up with a shoestore’s worth. When I visited his loft in Cannon Beach, it was filled with two-by-four racks covered with drying sneakers. He sold them on the street, along with his usual trinkets, for $30 each, and took in $1,300. “Is the shoe worth its salt?” quipped Jim Ingraham. He and I both took to wearing sea sneakers— in my case, a pair of fluorescent-pink Nike Flights that Steve gave me. Better yet, Steve collected even more data than he did sneakers. He had notes on where and when sixteen hundred shoes had washed up; without him, I might have collected only a third or half as many reports. All told, we located “point B” for 2.5 percent of the shoes washed off the Hansa Carrier—almost as good as the 2.8 percent reporting rate for thirty thousand scientific message bottles released near the same site in 1958 and 1959 as part of the International Geophysical Year. Media coverage, swap meets, and Steve’s diligence had proven nearly as effective as bottled pleas at eliciting responses from finders. It was solid data, good science. And it was the beginning of a flotsam-monitoring network that now circles the globe—thousands of sharp-eyed field monitors, volunteers in the search for telltale flotsam and indicator jetsam. The sneaker spill introduced me to the world of beachcombing, a culture I had only brushed up against before but from which I’ve since learned a great deal. Beachcombing appeals to deepseated impulses and aspirations—to the scientist, explorer, collector, and treasure hunter in everyone and, deepest of all, to the inner hunter-gatherer. It is poor man’s oceanography, research as play, unconstrained by professional ambition and open to everyone with eyes to see and feet to walk. Many beachcombers are uncelebrated salt-of-the-earth types; some are salty dogs. If they weren’t seeking washed-up treasures and curiosities, they might be home keeping scrapbooks or restoring old cars. Often they have little formal education, but they’re far more intelligent and inquisitive than many of the academics I’ve known. Beachcombing is a hobby—an unfashionable word these days—that opens up on everything else. Franklin D. Roosevelt credited his uncanny knowledge of world geography and history to his lifelong passion for stamp collecting. Likewise, to be interested in beachcombing is to be interested in everything. Beachcombers are the keepers of the ocean’s memory, sifting and sorting the chaotic surfeit thrown up by waves and tides, transmuting trash into artistic and scientific gold.