Pragmatism and Truth

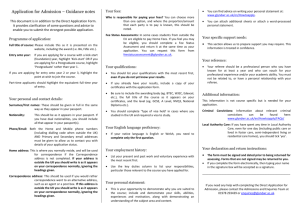

advertisement