Leadership Ltd: White Elephant to Wheelwright

Leadership Ltd: White Elephant to Wheelwright

©

Forthcoming in Outlook

Keith Grint

Complaints about leaders and calls for more or better leadership occur on such a regular basis that one would be forgiven for assuming that there was a time when good leaders were ubiquitous. Sadly a trawl through the leadership archives reveals no golden past but nevertheless a pervasive yearning for such an era. An urban myth like this ‘Romance of Leadership’ – the era when heroic leaders were allegedly plentiful and solved all our problems - is not only misconceived but positively counter-productive because it sets up a model of leadership that few, if any of us, can ever match and thus it inhibits the development of leadership, warts and all. It should be no surprise, then, to see, for example, the continuous re-advertising of vacancies for head teachers when the possibilities of success are either beyond the control of individuals or so clearly defined by comparative reference to Superman and

Wonderwoman that only those who can walk on water need apply.

The traditional solution to this kind of recruitment problem, or the perceived weakness of contemporary business chief executives or directors of public services, is to demand better recruitment criteria so that the ‘weak’ are selected out, leaving the

‘strong’ to save the day. But this is to reproduce the problem not to solve it. An alternative approach might be to start from where we are, not where we would like to be: with all leaders – because they are human - as flawed individuals, not all leaders as the embodiments of all that we merely mortal and imperfect followers would like them to be: perfect. The former approach resembles a White Elephant – in both dictionary definitions: as a mythical beast that is itself a deity, and as an expensive and foolhardy endeavour. Indeed, in Thai history the King would give a White

Elephant to an unfavoured noble because the special dietary and religious requirements would ruin the noble.

The White Elephant is also a manifestation of Plato’s approach to leadership, for to him the most important question was ‘Who should lead us?’ The answer, of course, was the wisest amongst us: the individual with the greatest knowledge, skill, power, resources of all kinds. This kind of approach echoes our current search criteria for omniscient leaders and leads us unerringly to select charismatics, larger than life characters and personalities whose magnetic charm, astute vision and personal forcefulness will displace all the bland and miserable failures that we have previously recruited to that position – though strangely enough using precisely the same selection criteria. Unless the new leaders are indeed Platonic Philosopher-Kings, endowed with extraordinary wisdom, they will surely fail sooner or later and then the whole circus will start again, probably with the same result.

An alternative approach is to start from the inherent weakness of leaders and work to inhibit and restrain this, rather than to assume it will not occur. Karl Popper provides a firmer foundation for this in his assumption that just as we can only disprove rather than prove scientific theories, so we should adopt mechanisms that inhibit leaders rather than surrender ourselves to them. For Popper, democracy was an institutional mechanism for deselecting leaders, rather than a benefit in and of itself, and, even though there are precious few democratic systems operating within nonpolitical organizations, similar processes ought to be replicable elsewhere. Otherwise, although omniscient leaders are a figment of irresponsible followers’ minds and utopian recruiters’ fervid imagination, when subordinates question their leader’s

D:\726972757.doc © Keith Grint, 2004 1

direction or skill these (in)subordinates are usually replaced by those ‘more aligned with the current strategic thinking’ – otherwise known as Yes People. In turn, such subordinates become transformed into Irresponsible Followers whose advice to their leader is often limited to Destructive Consent: they may know that their leader is wrong but there are all kinds of reasons not to say as much, hence they consent to the destruction of their own leader and possibly their own organization too.

Popper’s warnings about leaders, however, suggest that it is the responsibility of followers to inhibit leader’s errors and to remain as Constructive Dissenters, helping the organization achieve its goals but not allowing any leaders to undermine this. Thus Constructive Dissenters attribute the assumptions of Socratic Ignorance rather than Platonic Knowledge to their leaders: they know that nobody is omniscient and act accordingly.

Of course, for this to work subordinates need to remain committed to the goals of the organization while simultaneously retaining their spirit of independence from the whims of their leaders, and it is this paradoxical combination of commitment and independence that provides the most fertile ground for Responsible Followers.

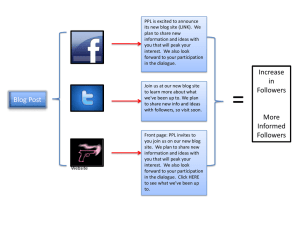

Autocracy & Cult Leader

Irresponsible Followers

Heterarchy & Socratic Leader

Responsible Followers

Increasing

Commitment

Hierarchy & Employer

Uncommitted Employees

Anarchy & Sub-Contractor

Independent Consultants

Increasing

Independence

As the figure above implies, with increasing commitment the subordinates turn from uncommitted employees and independent consultants into followers, but whether those followers are responsible or irresponsible depends upon the level of independence. Thus Cult Leaders beget Irresponsible Followers, uncommitted employees are held in place only by formal hierarchies rooted in reward and punishment, and sub-contractors can, at best, retain only independent consultants.

Only Socratic Leaders who are aware of their limits can inhabit a heterarchy – a moving hierarchy where leadership shifts with the time and space – and these attract and retain Responsible Followers who are committed to the organization but independent of the particular leader in place at that time.

The attribution of god-like qualities by irresponsible followers to allegedly omniscient leaders also generates an equivalent assumption about the power of leaders. While Plato’s leaders rest like mythical Greek gods in mount Olympus manipulating the lives of mortals at will and with irresistible power, Popper’s leaders should be resisted for precisely this reason. Yet it should also be self-evident that an individual can have virtually no control over anything or anybody - as an individual .

Indeed, we have known for a long time that leaders spend most of their time talking - not actually ‘doing’ anything else. In effect, leaders might pretend to be omnipotent, to have the future of their organizations and its members in their hands, but this can only ever be a symbolic or metaphorical control because leaders only get things done

D:\726972757.doc © Keith Grint, 2004 2

through others. In short, the power of leaders is a consequence of the actions of followers rather than a cause of it. If this were not so then no parents would ever be resisted by their children, no CEO would ever face a defeat by the board of directors, no general would suffer a mutiny, and no strikes would ever occur. That they do should lead us to conclude that no leader is omnipotent and that the kind of leadership is a consequence of the kind of followership, rather than a cause of it. Thus while

Plato’s leaders might construct formal hierarchies for subordinates to execute their perfect orders, Popper’s leaders work through networks and relationships because that’s where power is actually generated: it is essentially distributed like a wheel not concentrated in what is actually a White Elephant.

None of this is new: Helmuth von Motlke, Chief of the Prussian General Staff from 1857-1888, understood Clausewitz’s dictum that the local concentration of force was critical for military success and recognized that the nascent system of decentralized leadership already present in the Prussian army was crucial to achieving this. After all, a central commander in Berlin, or even 5 miles behind the battle had no way of understanding, let alone controlling, what was happening in each and every sector of the battle. The result was a system of leadership rooted in general directives, not specific orders, strategic aims not operational requirements, thereby enabling decentralized control that facilitated distributed leadership and the ability of local ground commanders to seize the initiative rather than await orders.

Perhaps an ancient Chinese story, retold by Phil Jackson (1995: 149-51), coach of the phenomenally successful Chicago Bulls basketball team, makes this point rather more emphatically. In the 3 rd century BC the Chinese Emperor Liu Bang celebrated his consolidation of China with a banquet where he sat surrounded by his nobles and military and political experts. Since Liu Bang was neither noble by birth nor an expert in military or political affairs some of the guests asked one of the military experts, Chen Cen, why Liu Bang was the Emperor. In a contemporary setting the question would probably have been: ‘what added value does Liu Bang bring to the party?’ Chen Cen’s response was to ask the questioner a question in return: ‘What determines the strength of a wheel?’ One guest suggested the strength of the spokes’ but Chen Cen countered that two sets of spokes of identical strength did not necessarily make wheels of identical strength. On the contrary, the strength was also affected by the spaces between the spokes, and determining the spaces was the true art of the wheelwright.

In sum, holding together the diversity of talents necessary for organizational success is what distinguishes a successful from an unsuccessful leader: leaders don’t need to be perfect but, on the contrary, they do have to recognize that the limits of their knowledge and power will ultimately doom them to failure unless they rely upon their subordinate leaders and followers to compensate for their own ignorance and impotence. Real White Elephants – albinos – do exist, but they are so rare as to be irrelevant for those who are looking for them to drag us out of the organizational mud; far better to find a good wheelwright and start the organizational wheel moving. In effect, leadership is the property and consequence of a community rather than the property and consequence of an individual leader.

References: Jackson, P. (1995), Sacred Hoops New York: Hyperion.

Keith Grint is Professor of Leadership Studies and Director of the Lancaster

Leadership Centre, Lancaster University Management School.Email: k.grint@lancaster.ac.uk

D:\726972757.doc © Keith Grint, 2004 3