Interview: Professor Keith Grint The Arts of Leadership

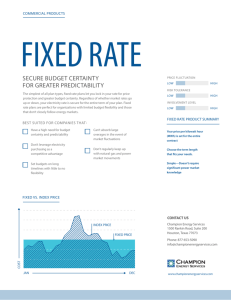

advertisement

Cranfield School of Management Interview: Professor Keith Grint The Arts of Leadership TT Why leadership, why now? Grint Good question – here's the short answer to that. I think people have been interested in leadership for thousands of years, but there is an issue about why has it come to the fore now. I suppose it has been building really since the end of the Second World War which is when a lot of so called professional leadership research starts, and its fruition in the last decade or so, I guess, to me looks like a desperate desire on the part of several people to find somebody else to explain or blame for the current situations that we find ourselves in. So if you look historically there was always some new way of explaining what is going on and eventually you end up with something called leadership as an explanation for what is going on. The implication of that would be that – and perhaps leadership is just another fad or fashion which will fade away in time, although I think again if you take the longer perspective there always is something about leadership – it's just that under certain circumstances and certain timeframes it appears to become more important than others, so my guess would be that in times of uncertainty people very often look for certainty and it may well be that what we have entered in the last decade is a period of significant global uncertainty and under those conditions people look for the answer and one of the aspects of leadership is it's allegedly the provider of answers. The fact that it probably doesn’t provide many answers is a separate issue, but I think that is probably an explanation for why leadership and why now. TT So given that uncertainty then, how would you frame that, coping with that uncertainty through leadership. Grint Well, I think there are two diametrically opposed ways of understanding that question – one is to take the conventional assumption that we could work backwards from Durkheim, a French sociologist writing at the end of the 19th century, picks up on the notion of the sacred for leadership, and for him there is something to do with leadership which provides this certainty for followers and followers are desperate for something which is above and beyond them, which they can look for and aspire towards. Knowledge Interchange Podcasts Page 1 Cranfield School of Management Professor Keith Grint But simultaneously that notion of the sacred involves the opposite side of the coin, which is the scapegoating role. So for Durkheim leaders are both saints and scapegoats and that is the kind of deal that you get. You provide the certainty allegedly, and then when it is exposed because actually you probably aren’t going to be the certain provider, the certainty provider, that is when you become the scapegoat. So on the one hand there is a kind of traditional way of explaining the notion of the search for certainty is this desperate search by followers for certainty in the motives and destinations of the skills of the leader. And the opposed side of that is work by people like Ronnie Heifetz who has argued that the primary role of leaders is actually not to take on the responsibility of the certainty, ie to push back the answers for those kinds of questions about what we are doing and how we should be doing it, which direction we should be going in, to push that back up on the followers because ultimately leaders can’t supply the answers. So, Heifetz’s argument is that the important role for leaders, and the most difficult role, because this runs counter intuitively, is not to provide certainty, not to provide the answers, but to provide a forum whereby followers can construct collectively answers to very difficult problems. TT So you seem to have got several things there: you have got followers, you have got certainty, you have got leaders, but in your books you seem to critique some quite cherished and common sensical, if you can call it that, notions of leadership. What is with the critique? Why are you trying to unsettle those aspects? Grint I think it is trying to understand it from the same perspective as Heifetz to a certain extent, that actually when you look historically at what leaders have achieved, first of all it is actually very difficult to know whether they are directly responsible for the achievements – so we attribute all kinds of things to leaders, but we seldom have the empirical evidence to be able to say X did this. What we can say is X was there at the same time as this happened, but that doesn’t necessarily mean anything – it's just a correlation rather than the causation. So there is always a difficult issue about trying to understand the particular role that leaders play. And the other element of that is to think well, if we are not absolutely sure, why is it that we seem to be absolutely sure? And I think this runs back into the Durkheimian perspective that there appears to be this desperate need by people to look for certainty and under those conditions what I would argue is that leaders get the followers they deserve, and vice versa. So, if your leader appears to be an arrogant and godlike creature, it is probably because you as a follower are not doing enough to constrain that approach. TT Or whether you want that approach. Knowledge Interchange Podcasts Page 2 Cranfield School of Management Professor Keith Grint Grint Or if you want that approach that is precisely what you get. So this relationship between leaders and followers strikes me as being one of the most important aspects of leadership. That we have focused for far too long on the characteristics and the competencies and the traits of individuals, and not enough on what is the relationship between leaders and followers, or leadership as a collective phenomena rather than an individual phenomenon. So that seems to me to be able to explain much more than just an assumption that if you get the right leader you can just relax and get on with your life because somebody else will take the right decisions and you are not responsible. And I think ultimately that issue of responsibility seems to me to be critical. Leadership is a way of avoiding responsibility because we attribute things to people and allow them to do things that we shouldn’t allow them to do, but because that enables us not to be responsible for subsequent events it's actually quite a kind of both risk avoiding and a comforting approach to the way that organisations and life is run through. TT Interesting. So the question around – this rather popularist question around – are leaders born or made, it would seem that we need, we want and need leaders. How do you even approach that very basic question? Grint Well, the quick answer to are leaders born or made is that all leaders are born in the sense that as far as I know there are no leaders that have not been born. So that answers that question. Second question is what is the role of the made bit in this and I think one way of understanding of it would be to look at significant sports people. If you take Jonny Wilkinson or David Beckham who have been prodigiously talented. So some people appear to be born with more talents than other is certain areas, but that doesn’t necessarily make them great – what makes them great is a huge amount of practice and dedication. So, in terms of are leaders born or made, I am sure there are some people who do appear from very early on to have great potential, but whether they fulfil that potential depends on what they do with that potential in the first place. It's almost – it's not an insignificant question, but it's not a relevant question in the sense of, well if you are born there is nothing we can do about it anyway. So, in that sense, it is an irrelevant question. It's relevant in the sense that can you therefore pick out certain kinds of people, or certain kinds of personality traits and does that lead to significantly improved leadership. I think the answer to that is very confused. I haven’t seen a great deal of empirical research looking at children and tracing through their leadership abilities across time – there simply isn’t that kind of material. There are individuals that we know about as young children, but there doesn’t seem to me to be a great deal in the Knowledge Interchange Podcasts Page 3 Cranfield School of Management Professor Keith Grint literature which says when you trace a thousand children, you pick out the leaders and they end up as leaders. We don’t know that to be the case at all and there are always individuals that turn out to be significant, like Adolf Hitler for example, who as a child and as a teenager is a nothing and a nobody going nowhere. So it is difficult to say that all these people who are significant start out as significant, with significant leadership abilities. It doesn’t seem to be the case. TT But would the lack of uncertainty – if you can put it that way – around that correlation, what does that imply in the development of leaders. Are we asking the wrong questions – how does that relate to development of leaders? Grint One of the consequences of this assumption about the role of leaders and the effectiveness of leaders strikes me as running back into one of Machiavelli’s rather nice lines about everybody can see the leader, but few can touch him in his terms. The implication of that is that we actually don’t know very much about leaders, we see them on TV all the time and we hear them, but we don’t know whether in fact they are as good or as bad as they seem to be and what Machiavelli I think is suggesting is that this distancing mechanism is an important aspect of successful leadership – that when you get closer to people, you realise that they have like everybody else, lots of warts, but when they are distant they don’t. So the closer you get to significant individuals, these leaders that we are talking about, the more they appear to be quite normal like everybody else, but if you are distant from them, they don’t. So one of the things that comes out from this, I think, is that the skill with which successful leaders control media sources and media influences and their public personas and if you are not in control of that then you probably have a problem because I think we still have this assumption that our individual leaders are significant, so what do we know about them? The answer is very, very little, but what we do know about them is either controlled by their media or else they are under control of the media. So it's really an issue in terms of how much information do you have and how much do you actually know about both the individuals and situations – and the answer is very little. TT You make it sound like some kind of alchemy there, and you call this book Arts of Leadership. Is there a reason for it being art as distinct from science of leadership? Grint I think the alchemy bit is quite interesting. I think one way of understanding this is to think about the worst thing which is Knowledge Interchange Podcasts Page 4 Cranfield School of Management Professor Keith Grint prevalent now – the Labour government, for example, has often been damned as one full of spin, but that implies that there is both a truthful version and a spun version of the truth and to go back to my previous point about lack of information and knowledge, we almost never know whether something is actually true or not. What we have is a basis of trust for taking people’s opinions as truth, so whether there ever were, for example, weapons of mass destruction in Iraq was never really based on information about which we could verify, it's really based on trust. Do you trust the people saying that there are, or trust the people saying that there aren’t? And it's not about empirical data – none of us, virtually none of us have got have got the empirical data to be able to answer the question one way or the other. So the alchemy bit is quite interesting in that it implies there is a lot of smoke and mirrors, but there is almost no way of getting beyond the smoke and mirrors – that is the point, there isn’t a transparent version of leadership. There is just different versions of leadership. Transcript prepared by Learning Services for the Knowledge Interchange www.cranfield.ac.uk/som Knowledge Interchange Podcasts Page 5 Cranfield School of Management Produced by the Learning Services Team Cranfield School of Management © Cranfield University 2007