Emergency Ultrasound of the Abdominal Aorta

advertisement

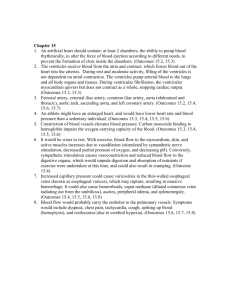

Emergency Ultrasound of the Abdominal Aorta Geoffrey E. Hayden, MD Director of Emergency Ultrasonography Vanderbilt Emergency Medicine Background and Anatomy: The diameter of the aorta is approximately 2 cm in the abdomen and tapers distally The upper limits of normal for aorta diameter are 2.5 cm at the diaphragm and 1.8 cm at the bifurcation Aortic branches: Celiac trunk: anterior wall approximately 1-2 cm below the level of the diaphragm; it gives off the splenic artery, the common hepatic artery, and the left gastric artery The splenic artery passes to the left along the superior border of the pancreas Superior mesenteric artery (SMA): anterior wall of the aorta approximately 2cm from the celiac trunk Renal arteries: off the lateral wall of the aorta just distal to the SMA Inferior mesenteric artery (IMA): anterior wall just proximal to the bifurcation Common iliac arteries arise at the bifurcation approx. at the level of the umbilicus or the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra Pathology: There are progressive changes in the aorta’s intimal and medial layer resulting in a gradual dilatation of the external diameter of the abdominal aorta This dilatation is considered aneurysmal when the external diameter becomes 1.5 times that of normal An aneurysm is defined as an abnormal focal dilatation of the vessel wall that measures greater than 3 cm Overwhelming majority of ruptures occur when an aneurysm is greater than 5 cm The natural history of an aneurysm is to expand at an average rate of 0.4 cm per year Aneurysms enlarge at an average rate of 0.4 cm per year, with a high individual variability Threshold for rupture tends to occur at greater than 5.0 cm in size (22% risk of rupture within 2 years) Risk of rupture is estimated at 1-3% per year for aneurysms 4-5 cm; 6-11% per year for aneurysms 5-7 cm; 20% per year for aneurysms greater than 7 cm The left retroperitoneum is most common site for rupture; with this rupture, there may be normal hemodynamics initially without significant blood loss Demographics and risk factors: Multiple factors, including HTN, smoking, age, atherosclerotic vascular disease, and genetics play a role; strangely, diabetes actually decreases the risk Adult males over 55 years of age are considered to have aneurysms when the aortic diameter reaches 3.0 cm or greater The incidence of AAA is 11% in men over 65 years of age, and the average age at presentation is 75 years M>F at 7:1 ratio Over the past 3 decades, there has been a 300% increase in overall prevalence of AAA Presentation: Symptoms and signs of AAA are nonspecific It does not reveal itself with sufficient predictive value by historical features or PE Symptoms range from vague abdominal and back discomfort to severe, deep back pain or abdominal pain; may also see a femoral neuropathy (causing hip and thigh pain, quadriceps muscle weakness, and positive psoas sign) May also produce intramural clot which can embolize to the LE, with consequent pain and vascular changes Clinical shock is present between 35-70% of patients but tachycardia is present in only 50% Triad of abd pain, pulsatile abd mass, and hypotension only present in 1/3 of patients In ruptured AAA, most still have normal femoral pulses Asymmetry or absence of femoral pulses is more commonly associated with aortic dissection Most common errors include diagnosing the patient with nephrolithiasis, diverticulitis, intestinal ischemia, pancreatitis, appendicitis, perforated viscus, bowel obstruction, musculoskeletal back pain, GI bleed, or AMI Ultrasound and AAA: Bedside ultrasound has been reported to be 100% sensitive for the presence of an AAA Sensitivity for detecting extraluminal blood is around 4% Aneurysmal dilatation is most often confined to the infrarenal aorta and usually terminates proximal to the bifurcation The iliac arteries are involved in 40% of patients with AAA (iliac artery aneurysm >1.5 cm) Sono Technique: Typically use a 2.5-5MHz curved array probe Views from the subxiphoid area to the umbilicus in the patient’s midline Probe pointer at 9 o’clock, firm pressure to abdomen Step 1 is to identify the anterior vertebral body; densely hyperechoic, concave down, with posterior acoustic shadowing Two vascular, anechoic structures are present immediately anterior to the vertebral body; with the probe indicator pointing to the patient’s right side, the aorta is on the right side of the U/S screen (patient’s left) and the IVC is on the left side of the screen The aorta tends to have thicker, more echogenic walls; it also tends to be more pulsatile (not a perfectly consistent feature), and it tends not to be compressible; the IVC does not have branches as does the aorta (celiac, SMA, etc.) Measurements are made from outer wall to outer wall The ultrasound exam should involve visualization of the entire length of the abdominal aorta Probe must be perpendicular to the aorta, in order to maximize the angle of insonation Move down the abdomen in 0.5-1 cm increments in the transverse plane Turn the probe clock-wise to 12 o’clock to obtain a longitudinal view of the aorta Follow from the mid-epigastrium to the bifurcation May see lateral cystic shadowing (edge artifact) and shadowing from calcified plaques within the lumen of the aorta If there are technical limitations that restrict your exam, consider the coronal view as an alternative Using the liver as an acoustic window, place the probe in the mid-axillary line at 12 o’clock Image through the ribs, preferably below the costal margin “Take a deep breath and HOLD” Look for: Real-time views of the entire length of the aorta both in transverse and in longitudinal Identify the abdominal vascular anatomy: celiac trunk, splenic vein, SMA, and IVC Save images as follows: Aorta transverse HI Aorta transverse MID Aorta transverse LO Aorta LONG Also save video clips of the entire length of the aorta both in transverse and in longitudinal Pitfalls: Obesity, bowel gas, abdominal tenderness, positioning, wounds, etc. may all limit the aorta exam Longitudinal views of the aorta may be influenced by a “cylinder tangent effect” (off center slice will show a reduced diameter) Confusing the IVC for the aorta Failure to consider the diagnosis A small aneurysm does not preclude rupture If AAA is identified, it may not be the cause of the patient’s symptoms Saccular aneurysms are easily overlooked Inappropriate caliper placements (outer wall to outer wall!) may underestimate lumen diameter and under-call AAA Pearls: If you identify a good sono window with great aorta visualization, fan your transducer up and down to maximize your imaging area before physically moving down the abdomen The elderly may have tortuous aortas that become quite eccentric….don’t rely on the midline Bowel gas can be displaced to the right and left with gentle pressure applied through the transducer in an anterior to posterior direction If bowel gas obstructs your view, the transducer can be placed in the right axillary line; this uses the liver as an acoustic window; the patient must be rolled into a left lateral decubitus position