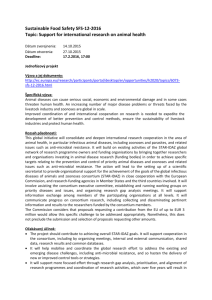

References - Department for International Development

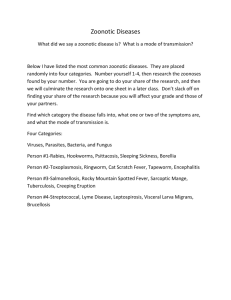

advertisement