issues in materials development for intercultural learning

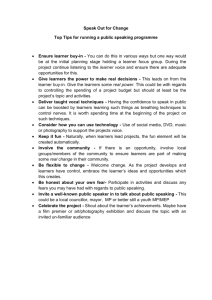

advertisement

Here and there: issues in materials development for intercultural learning Alan Pulverness This is the text of a paper given at the Culture in ELT Seminar - Intercultural Materials in the Classroom and on the Web organised by the British Council at Kraków 23-25 January, 2004. In it Alan Pulverness addresses twelve major questions facing teachers who want to add this dimension to the learning materials they produce. 1. Is intercultural awareness just a buzzword? What justification is there for attending to students’ own cultural context in teaching materials? Over the last 15 years or so, there has been an increasing trend in European education towards a concept of ‘language across the curriculum’, or at least cross-curricular approaches within the foreign language class. This tends to break down strict subject boundaries, so that the foreign language lesson can potentially embrace mathematics, history, geography, biology etc. and first language culture. In fact, a cross-curricular perspective creates the potential for foreign language teachers to take on a much broader and more satisfying identity, as educators, rather than merely foreign language trainers. There is a positive case to be made for a ‘Janus-faced’ approach. Claire Kramsch makes the point that ‘[T]he teacher of culture is faced with a kaleidoscope of at least four different reflections of facts and events’ (1993: 207); as teachers of ‘language-and-culture’ (Byram, Morgan & colleagues 1994), we should be concerned with more than simply the two dimensions of observing the cultural Other and observing how the others see themselves; we should be equally concerned with cultural self-reflexiveness – ‘seeing ourselves as others see us’ – and seeing how we see ourselves. The experience of learning another language is more than simply the acquisition of an alternative means of expression. It involves a process of acculturation, akin to the effort required of the traveller, striving to come to terms with different social structures, different assumptions and different expectations. To pursue the metaphor, when the traveller returns home, his/her view of familiar surroundings is characteristically modified. The language learner is similarly displaced and ‘returns’ with a modified sense of what had previously been taken for granted – the language and how it makes meaning. This sensation of seeing one’s own language and culture refracted through the medium of a foreign language and culture reflects what was described by the Russian Formalist critic, Viktor Shklovsky (1917), writing about Tolstoy’s literary technique, as ‘defamiliarisation’, or ‘making the familiar seem strange’: After we see an object several times, we begin to recognise it. The object is in front of us and we know about it, but we do not see it - hence we cannot say anything significant about it.... Tolstoy makes the familiar seem strange.... He describes an object as if he were seeing it for the first time, an event as if it were happening for the first time. (in Lodge 1988: 21) For the majority of learners encountering a foreign language for the first time, their own culture is so familiar, so much a given, that they ‘do not see it’. Their culture provides them with one way of looking at the world and their language with one way of doing so. The experience of defamiliarisation involved in foreign language learning, described by Byram (1989: 137; 1990: 19) as the ‘modification of monocultural awareness’, suggests that there is largely untapped potential in teaching materials for focusing as much on the source culture as the stimulus culture, and on the effect upon the learner of this modification. The implication of an intercultural approach is that foreign language learners should be concerned with more than just acquiring a different communicative code and certainly with more than merely amassing information about a ‘target language culture’. As Byram suggests, entering into a foreign language implies a cognitive modification that has implications for the learner’s identity as a social and cultural being, and suggests the need for materials which privilege the identity of the learner as an integral factor in developing the ability to function fully in what Kramsch calls cultural ‘third places’ (1993: 233-259). For the learner, as for the immigrant, linguistic adjustment may produce the deepest feelings of cognitive dissonance, creating a seemingly unbridgeable divide between things in the world and the language available to refer to them. Eva Hoffman has written eloquently about this disjunction in her memoir of moving from Polish into English, Lost in Translation: There are some turns of phrase to which I develop strange allergies. ‘You’re welcome,’ for example, strikes me as a gaucherie, and I can hardly bring myself to say it - I suppose because it implies that there’s something to be thanked for, which in Polish would be impolite. The very places where language is at its most conventional, where it should be most taken for granted, are the places where I feel the prick of artifice. [...] The words I learn now don’t stand for things in the same way they did in my native tongue. ‘River’ in Polish was a vital sound, energized with the essence of riverhood, of my rivers, of my being immersed in rivers. ‘River’ in English is cold - a word without an aura. It has no accumulated associations for me, and it does not give off the radiating haze of connotation. It does not evoke. (1991: 106) With her now finely nuanced command of a second language, Eva Hoffman recaptures her initial resistance to the language, which she has been able, magnificently, to overcome. Her insight into this condition reminds us how uncomfortable a new language can feel, even when we have become quite proficient users of that language. When teaching adolescents, it is generally difficult to predict, beyond immediate academic purposes, what future use(s) they will have for a foreign language. The practice of needs analysis works very well in EOP or ESP contexts, but is inevitably much fuzzier at secondary school level. We presume - probably quite correctly - that a foreign language (and for all kinds of geo-political and technological reasons English is self-evidently the definitive example) will be useful, both in terms of getting a job and doing it. However, we cannot predict with any degree of certainty exactly how the foreign language will serve our learners’ future needs, or if indeed it will. So, despite the fact that education across Europe in general is becoming increasingly utilitarian, increasingly focused on socio-economic needs, foreign language teaching continues to retain a much larger educational value - broadening learners’ horizons, enabling them to understand and appreciate difference. Whatever career choices they eventually make, and whether or not they have the opportunity to make use of their foreign language(s) in the future, the educational value of foreign language learning has to do with education for citizenship. To some extent, this has always been the case, but in the context of an expanding European Union, and in the face of rapidly increasing globalisation, this function seems more important then ever. It seems to me that this educational project should equip learners with the resources to define and assert their own cultural identity; to gain an understanding of other cultural identities; and, crucially, to be able to ‘read’ the messages that will confront them - and when necessary, to resist them. I may seem to have strayed from the specific question of whether foreign language teaching should include an element of teaching and learning about students’ own culture, but if we are to extend our function as foreign language teachers, we need to have more than a vague sense of why this might be an important thing to do. There may not be any overwhelming consensus about the sequencing of a functional syllabus, but most materials writers adopt the conventional strategy in the opening units of most beginners’ books for foreign language teaching of equipping learners with the basic linguistic routines they will require to introduce themselves. For any kind of interpersonal encounter, it clearly makes good sense to start with the ‘I’, and this perspective can indeed be extended to quite a high-level competence in terms of representing the learner’s own culture to others - becoming, in effect, ‘ambassadors’ of their own culture. 2. Whose perception of a culture should the teacher/materials writer adopt - the representatives of that culture or the outsider’s? I would want to say that the most effective approach is to draw on a multiplicity of perceptions. As a materials writer, within the practical limits imposed by copyright and publishing constraints, this is comparatively easy to achieve: the conscientious materials writer is at liberty to anthologise all kinds of perceptions and thus to create a dialogic interplay of discourses. This is certainly one way of dealing with the problem of generalisation and stereotyping. The teacher, on the other hand, may have a lot less freedom: s/he may be forced to work with a more monologic coursebook and may not have ready access to supplementary materials that would introduce an element of cultural polyphony. It should, however, be the teacher’s responsibility to do whatever s/he can to diversify the range of voices/perceptions to be made available in the classroom. This may be done with all kinds of authentic materials - songs, advertisements, photographs, mini-texts, articles, brochures, leaflets etc etc. 3. How can authentic materials be used to teach the students’ own culture? Should such teaching be conducted in L1 or L2? This raises two linked issues: one is purely linguistic - the use of L1 - while the other is related to the relevance and appropriacy of students’ own cultures. The context of cultural learning offers an important justification for the presence of the L1, namely the inter-penetration of language and culture. Language is not simply a vehicle for conveying cultural meaning - cultural meaning is deeply embedded in language. In many cases, the language is the culture, or at least one of the most highly articulated representations of the culture. Therefore, if we accept the proposition that students’ own culture should occupy a central place in cultural learning, then it seems axiomatic that some of the treatment of this ‘home’ culture will quite naturally - and appropriately - be in the students’ own language. Translation, too, has a place - not the often painful attempts to produce a faithful rendering of the original text, but translation tasks which perform other real-world cross-linguistic functions, such as summarising, interpreting and (in one of the key terms of the Council of Europe’s Common European Framework) mediating. Of course, ‘authentic materials ... to help teach the students’ own culture’ need not be in the students’ own language: the language teacher who acknowledges the relevance of the students’ own culture, but who has serious reservations about using excessive stretches of the L1, need not look very far for a wide range of useful texts written in English and dealing with the ‘home’ culture: (sadly) occasional articles in the British ‘quality’ press (most of which have searchable databases on their Web pages); books and essays on Central & Eastern Europe (e.g. Eva Hoffman, Slavenka Drakulić, Vitali Vitalyev); English-language journals such as The Central Europe Review; English-language newspapers such as The Warsaw Voice; tourist materials and various kinds of promotional materials. Going back to Kramsch’s ‘kaleidoscope’ of cross-cultural perceptions, it is texts like these that are not merely useful, but essential, tools to decode and understand what is going on within as well as between cultures. 4. Most students will not ever live in a target language country, but will use English in multi-cultural settings, such as doing business with people whose mother tongue is not English. What are the similarities and differences between teaching language-and-culture in foreign language and second language contexts? Much published language teaching material seems designed to promote what Gillian Brown (1990: 12) has called ‘cosmopolitan English’, partly as a consequence of idealised notions of English as a lingua franca, and partly to ensure maximum worldwide sales by avoiding any taint of cultural specificity. I feel very strongly that this attempt to separate language from its cultural roots is likely at best to prove inadequate, because it aims at developing the foreign language as a neutral code, free of its history, free of its social moorings – in short free of culture. Some kind of communication may result, but it seems to me that the result is likely to be at best an impoverished form of communication. The concept of something called ‘International English’ is the basis for a popular argument against the inclusion of a cultural dimension in the language classroom. I feel that it rests on a weak and unproven construct of English fulfilling the role that the proponents of Esperanto intended for their ‘international’ language. It ignores the fact that English, like any other language, is the outcome of long and complex social history, and equally it ignores the fact that interlocutors making use of English as a mutually comprehensible means of conducting transactions will themselves be speakers of languages with equally long histories and equally rich cultural meanings. I doubt whether the lingua franca argument ought to inhibit us from including a cultural dimension in the foreign language classroom. Clearly, the second language context will always be far more demanding, for teachers and for students, as the objective is likely to be a degree of assimilation - or at least sufficient understanding and sensitivity to operate comfortably in the host community. But since our students’ future needs are relatively unpredictable, perhaps the overlap between the second language and foreign language contexts are greater than we may imagine. However, as long as we equate ‘teaching culture’ with teaching about the Other culture, there may seem to be little justification for devoting precious teaching time to something which is, at best, of speculative value. If on the other hand, we view ‘teaching culture’ as raising inter-cultural awareness - as much concerned with thinking about one’s own culture as learning about the Other - then no justification is necessary - it becomes an educational goal rather than a purely linguistic one. 5. To what extent should we encourage students to assume the behavioural patterns of a target language culture? The simple answer is to whatever extent our students wish to do so. In other words, I don’t think there can be a universal answer. In a sense this is very close to the question of how far we should encourage students to approximate to a native-speaker accent. It is commonly observed that immigrants fall into two broad categories with regard to accent - those who want to merge into the host community as far as possible and therefore aim to sound as British as the British (or as Polish as the Polish) and those who want to preserve their own first-language personae, and therefore resist any modification of their ‘foreign’ accent. It seems to me that the question of whether or not ‘to assume the behavioural patterns of the target language culture’ is subject to the same kind of attitudinal drives. Allied to this underlying conception of the self in relation to the target language culture, there are, of course, more practical considerations of the type that the business person may need to take into account - a much more conscious - and perhaps calculated - set of decisions as to whether there is more advantage to be gained through an attempt at behavioural congruence with representatives of the target language culture, or whether rigorously preserving one’s own cultural identity will elicit more sympathy, or simply be more attractive. 6. As teachers of EFL we often speak about ‘the target language culture’. But there are many English language cultures. (How) is it possible to reconcile the differences between different English-speaking cultures? How can we strike a balance between the different English speaking cultures in language classes? Teachers, being human, will perhaps inevitably tend to privilege the culture(s) that is/ are ‘closest to their heart’. There are complex, though quite apparent, reasons for the emphasis given in different places at different times to one English-speaking culture or another. In terms of the use-value of the foreign language, this is understandable and fairly irresistible: it would clearly be doing our students a perverse disservice if we were to concentrate, say, on New Zealand culture to the exclusion of other, more globally significant English-speaking cultures. However, linguistically, historically and politically, the spread of and consequent variation in English language and culture may well itself be a subject of great interest for students. We may not be able to ‘reconcile these differences’, and there is always the vexed question of limitations on teaching time, but we should certainly try to avoid conveying the impression that it is only British, or only American culture that counts. We also need to consider the practical classroom implications of the pluralistic attitude to English-speaking cultures that I have been advocating. The appropriate ‘balance’ will derive from a number of influences: underlying political and economic priorities; the geographical location of the school; the school’s, or the department’s policy; parents’ preferences; the content of course materials; the teacher’s own background - and, not least, the students’ interests. The challenge for the teacher, in the face of all these powerful influences, is to do as much as s/he can precisely to ‘strike a balance’. One interesting way of achieving this difficult goal may be to focus on texts and other materials which themselves relate to more than one English-speaking culture - such areas as the globalising influence of American popular culture, relations between the UK and former British Commonwealth countries, the incursions of African or Indian writing into the British literary landscape. 7. How does an intercultural approach modify the traditional language syllabus? Course materials are largely governed by a tacit consensus about what should constitute a language syllabus. Apart from a brief pendulum swing in the late 1970s, when the elaborated phrasebook of an exclusively functional approach almost entirely displaced grammar, and despite the development of multi-strand syllabuses, the structured, incremental grammatical syllabus remains the principal axis around which the overwhelming majority of coursebooks are organised. The overarching aim of the language syllabus is to develop a command of the language as a systematic set of resources. However, the focus of most teaching materials remains fixed on the content of these resources rather than on the choices that speakers (and writers) make in the course of social interaction. The cultural dimension of language consists of elements that are normally classed as ‘native speaker intuition’ and which may be achieved by only the most advanced students. As native speakers, we function effectively in our own speech communities not simply by drawing mechanically on an inventory of language items, but by employing the pragmatic awareness which enables us to make appropriate and relevant selections from that inventory. This awareness may not be wholly determined by cultural factors, but it is culturally conditioned. It includes elements such as forms of address, the expression of politeness, discourse conventions and situational constraints on conversational behaviour. Grice’s ‘cooperative principle’ (1975) and Lakoff’s ‘politeness principle’ (1973) have up to now made remarkably little impression on EFL materials. It is lack of awareness of such contextual and pragmatic constraints that is often responsible for pragmatic failure. Although teachers may incidentally address some of these features, there have been few attempts in published materials to deal systematically with the ways in which linguistic choices are constrained by setting, situation, status and purpose. Like many coursebook texts, tasks requiring oral interaction tend to be situated in neutral, culture-free zones, where the learner is only called upon to ‘get the message across’. One recent challenge to the centrality of grammar as an organising principle for the syllabus is to be found in the ‘Lexical Approach’ (Lewis 1993; 1997), with its insistence on language as ‘grammaticalised lexis’ instead of the customary view of ‘lexicalised grammar’. The coursebook inspired by Lewis’ work (Dellar & Hocking Innovations 2000; 2004), emphasises the significance of collocation and lexical phrases, partly subsumed under the category of ‘spoken grammar’, while key elements of a traditional structural are retained under the less dominant rubric of ‘traditional grammar’. This focus on how lexical items cluster together through use and constitute larger units of meaning provides an important design principle for materials that intend to combine cultural learning and language learning. Porto (2001) makes a strong case for taking lexical phrases as a foundation for developing socio-cultural awareness from the earliest stages of language learning: Given that lexical phrases are context-bound, and granted that contexts are culture-specific, the recurrent association of lexical phrases with certain contexts of use will ensure that the sociolinguistic ability to use the phrases in the appropriate contexts is fostered. (2001: 52-53) Another lexical area that might profitably be explored by materials writers is suggested by research into cognition and cross-cultural semantics (Wierzbicka 1991; 1992; 1997). Wierzbicka’s research methodology, at word- or phrase-level, as well as when dealing with broad semantic categories and longer stretches of text and interaction, is one that lends itself to adaptation by EFL materials writers. Her analyses are based on extensive collections of data, exemplifying the use of particular items in multiple contexts, from which she then begins to draw conclusions about the cultural specificity and the semantic limitations of key concepts. On a smaller scale, this rigorously inductive approach might have a particular appeal to learners who are in any case constantly engaged in just this kind of exploration of meaning, albeit in a relatively unstructured fashion. The increasing availability of affordable concordancing software should also make it possible before long for the coursebook treatment of this kind of activity to be open-ended and supplemented by providing learners with the tools to pursue their own further exploration. One of the most challenging aspects of moving into the culture of another language is the adjustment to different rhetorical structures. Learners have to cope receptively and productively, not just with word-level and sentence-level difference, but with different modes of textual organisation. While contrastive studies in rhetoric and text linguistics (e.g. Kaplan 1966; 1987) have explored the problematic nature of text and discourse across cultures, a great deal of language teaching continues to operate at sentence-level. It is generally only on EAP courses in academic writing that text structure receives any substantial attention. Yet sometimes radically different assumptions about the structuring of spoken and written discourse can produce a sense of cultural and linguistic estrangement that all learners have to struggle to come to terms with, often without any help from course materials. A number of recent coursebooks have tentatively included small translation tasks, usually at word- or sentence-level. More extensive translation activities could raise learners’ awareness of how differently ideas may be organised at text-level. For example, translating a source text and then comparing its structure with a parallel L1 text on the same topic and in the same genre, or using a ‘double translation’ procedure, i.e. translation into L1 and then back into L2, comparing the second version with the L2 original. Limitations of space will normally prohibit extensive treatment of longer texts within the coursebook, but here again the book can serve as a manual, equipping the learner with strategic competence and procedural guidelines as a basis for further work outside the book. The construction of cultural ‘third places’ is essentially a critical activity, as it forces learners to become aware of ways in which language is socially and culturally determined. Language awareness has become a rather hollow label, often (e.g. on many pre-service training courses) more or less synonymous with declarative knowledge about how the language works. Van Lier’s (1995) definition is more comprehensive and should alert us to the fact that language is always ideologically loaded and texts are always to be ‘mistrusted’: Language awareness can be defined as an understanding of the human faculty of language and its role in thinking, learning and social life. It includes an awareness of power and control through language, and of the intricate relationships between language and culture. (1995: xi) Critical Language Awareness (CLA) proceeds from the belief that language is always value-laden and that texts are never neutral. Language in the world beyond the coursebook is commonly used to exercise ‘power and control’, to reinforce dominant ideologies, to evade responsibility, to manufacture consensus. As readers, we should always be ‘suspicious’ of texts and prepared to challenge or interrogate them. However, in the foreign language classroom, texts are customarily treated as unproblematic, as if their authority need never be questioned. Learners, who may be quite critical readers in their mother tongues, are textually infantilised by the vast majority of course materials and classroom approaches. A CLA approach implies ‘a methodology for interpreting texts which addresses ideological assumptions as well as propositional meaning’ (Wallace 1992: 62), which would require students to develop sociolinguistic and ethnographic research skills in order to become proficient at observing, analysing and evaluating language use in the world around them. It would lead them to ask and answer crucial questions about a text: Who produced it? Who was it produced for? In what context was it published? It would encourage them to notice features such as lexical choice, passivisation or foregrounding that reveal both the position of the writer and the way in which the reader is ‘positioned’ by the text. It would offer them opportunities to intervene creatively in texts, to modify them or to produce their own ‘counter-texts’ (see Kramsch 1993; Pope 1995). It would empower students to become active participants in the negotiation of meaning rather than passive recipients of ‘authoritative’ texts. In short, it would transform language training into language education. 8. If language and culture are inseparable, what implications does this have for materials writers who try to produce internationally ‘consumable’ course books? Many writers (myself included) would agree that ‘language and culture are inseparable’. In my own case, the implication has been to move away from trying to produce ‘internationally ‘consumable’ course books’ and to become more involved in country-specific publishing. But for textbook writers who are going for the global option, I think there are some serious implications. One is to acknowledge the futility of trying to pursue the internationalist, English-as-lingua-franca model: this only seems to result in bland and characterless constructions of international conferences, airport lounges and hotel reception desks, which could be anywhere and nowhere, where people come from everywhere and nowhere, and everyone speaks Gillian Brown’s ‘cosmopolitan English’. This seems to be a severely limited approach, and the other implication for materials writers is to make a virtue out of cultural specificity, to make the point that language never exists or functions in a cultural vacuum, that it is never simply a neutral, a-cultural code. The objection that is raised, of course, is the potential irrelevance of such culturally specific materials for large numbers of learners, and so the corollary is to bring the learner into the material - not just paying lip-service to an intercultural perspective by inserting a ‘Now write about your country’ task in the bottom right-hand corner of a double-page spread, but finding ways throughout the materials of integrating the learner’s perspective, of acknowledging the experience and the knowledge of the world that the learner brings to the classroom. To develop cultural awareness alongside language awareness, materials need to provide more than a token acknowledgement of cultural identity (‘Now write about your country’) and address more thoroughly the kind of cultural adjustment that underlies the experience of learning a foreign language. One powerful means of raising this kind of awareness in learners is through literary texts which mimic or more directly represent experiences of cultural estrangement. A ‘whole way of life’ view of culture has trickled down into some ELT coursebooks, where iconic, tourist brochure images of Britishness have been replaced by material that is more representative of the multicultural diversity of contemporary British life. But since language training remains the primary agenda, the effect is often unproductive in terms of cultural understanding, with texts and visuals serving primarily as contextual backdrops to language tasks. Moreover, since the majority of coursebooks are designed to function in as diverse a market as possible, materials design is rarely capable of encompassing the learner’s cultural identity as part of the learning process. At most, learners may be called upon to comment on superficial differences at the level of observable behaviours. There is a great deal of incidental cultural information available in course materials, but it is on the whole an arbitrary selection, and crucially, it remains information - learners are not required to respond to it in terms of their own experience or integrate it into new structures of thought and feeling. The subculture of the language learner and the ‘small culture’ of the classroom tend not to be addressed. Moreover, the pedagogical implications extend beyond issues of content: if culture is seen as the expression of beliefs and values, and if language is seen as the embodiment of cultural identity, then the methodology required to teach a language needs to take account of ways in which the language expresses cultural meanings. An integrated approach to teaching ‘language-and-culture’, as well as attending to language as system and to cultural information, will focus additionally on culturally significant areas of language and on the skills required by the learner to make sense of cultural difference. A language syllabus enhanced to take account of cultural specificity would be concerned with aspects of language that are generally neglected, or that at best tend to remain peripheral in course materials: connotation, idiom, the construction of style and tone, rhetorical structure, critical language awareness and translation. The familiar set of language skills would be augmented by ethnographic and research skills designed to develop cultural awareness. There are encouraging signs in some recently published coursebooks of greater cultural relativism and more pluralistic representations of English-speaking cultures. But as long as courses continue to be produced for a global market and construed exclusively in terms of language training, such developments will remain largely cosmetic. It seems to me that the way ahead for integrated language-and-culture materials lies in various kinds of country-specific joint publishing ventures and as the Polish British Studies Web pages have demonstrated so effectively, in electronic publishing. It has to be acknowledged that such innovative projects remain the exception. ELT at large continues to be dominated by the mass market, ‘international’ coursebook. But here the teacher has a vital role to play in acting as an intercultural mediator and providing some of the cultural coordinates missing from the coursebook. I have been involved as consultant or writer in several joint projects in Central and Eastern Europe, and in Hungary I was fortunate to observe a wide range of classes in various parts of the country. All the classes I saw were working with coursebooks: Headway Elementary, Intermediate and Advanced; Access to English: Getting On; Blueprint 2; New Blueprint Intermediate; Meanings into Words 2. The teachers were all sufficiently experienced and confident to take subject matter present in coursebook units as a vehicle for the presentation of language items or the development of language skills and to use it as the basis for exploring cultural dimensions of the topic or theme. Coursebooks provide invaluable resources (topics, texts, visuals, language) and enable teachers and students to structure learning, but they also impose constraints which can be difficult to resist. Teachers who are conscious of this can easily become discouraged by the difficulty of obtaining suitable supplementary resources, but I was impressed by the ways in which all the teachers I observed made use of appropriate extra materials which enabled them to go beyond the coursebook - to use the currently fashionable commercial metaphor, to ‘add value’ to the coursebook. Examples included: a teacher’s own photographs of Hungarian and British houses; text and video extracts from Trainspotting; a poem (‘Neighbours’ by Kit Wright); National Readership Surveys table of socio-economic categories (from Edginton and Montgomery 1996); students’ own family photographs and Christmas cards; jumbled extracts from two contrasting ‘background’ books; students’ posters based on material collected during a study trip to Britain. These materials either compensated for cultural dimensions that were totally absent from the coursebook or took students well beyond the usual end-of-unit gesture of Now compare this with houses/festivals/occupations etc in your country. Some of the teachers took topics from coursebook units as springboards for lessons which focused on content rather than concentrating exclusively on language points. This is not to say that language learning was absent, or even incidental, but the primary objectives were clearly to develop critical thinking about cultural issues, resisting the tendency of the materials to use content only to contextualise the presentation and practice of language items. For example, one lesson sprang from a coursebook unit where the topic was homelessness, but the unit was about expressions of quantity. The lesson, however, was about homelessness, with practice of expressions of quantity arising meaningfully through her use of the material. There is a crucial distinction between classes that are driven by a language training agenda and those that are informed by cultural learning objectives. There is still a need, of course, for classes where the primary focus is language learning, but here, too, it is important that cultural learning is seen as an integral part of language education and not restricted to the ‘cultural studies lesson’. One lesson on writing was an excellent example of this kind of integration. The teacher’s primary aim was to raise students’ awareness of the conventions and structural norms of writing postcards and informal letters in English, but this was done by getting the learners to carry out a detailed contrastive analysis of a range of authentic texts (received by the teacher) in English and in Hungarian. Thus what could easily have been an exclusively English language lesson achieved its objectives through exposure to and reflection on representative samples of equivalent language behaviour in different cultural contexts. In any discussion of cultural behaviour, especially in classrooms, where teachers feel the pressure of time and other constraints, it is all too easy to resort to generalisations and to accept particular instances as being ‘typical’. One way to avoid this trap is to make use of materials (e.g. first-person narratives) which are self-evidently individual, or even idiosyncratic. Other, more difficult strategies are to remind students at appropriate moments that they should not over-generalise from particular examples, or to challenge their natural tendency to do so. This happened very interestingly in the lesson on homelessness, when the teacher prompted students to question the generalisations contained in the text, giving rise to the conclusion that ‘English people are various’! Another good example in the writing class was the teacher’s reminder to her students that they were reading individual examples of informal writing, which they should not necessarily regard as ‘typical’. The lessons I saw in Hungary were neither language lessons illustrating a few bits of cultural information nor lessons on culture with language learning as a kind of by-product. They all succeeded in different ways in combining language learning and cultural learning, so that although at some moments the emphasis may have been in one direction or the other, the overall effect was of lessons in which students were developing both kinds of knowledge as interrelated parts of the same enterprise. 9. Do good materials change teacher behaviour? Can the approach be effected through materials (alone)? I am sure that good materials can have a developmental effect on teacher behaviour, though it is unlikely that any change will be instantaneous. Any change in teacher behaviour is bound to be a slow and experimental process, consisting of a tentative series of minor accommodations. Teachers tend to be fairly conservative, sticking to tried and tested routines, and suspicious, or at least resistant to innovation. They will cautiously try something out, making small changes at the level of technique, which gradually build into major shifts in approach and methodology. This process is rarely smooth and consistent - there may be many false starts and discouragements, but gradually change does take place, and materials clearly have an important role to play. However, if the materials are too radically innovative, there is a real risk of rejection and ‘materials (alone)’ are not the answer. Materials informed by an approach that is likely to clash with the prevailing educational culture, or which require teachers to consider dimensions that they may previously have ignored, need to be introduced and mediated through some kind of teacher development programme. In a sense, publishers have always known this, and they invest significant amounts of time and money in getting their authors to do promotional talks and seminars, simply to create a ‘buzz’ among teachers for this year’s products (even when they are not hugely different from last year’s!). Real change in teacher behaviour, however, implies some fundamental change in underlying teacher attitudes and teacher beliefs, and this can only be accomplished by introducing colleagues to principles as well as practices. 10. How is it possible to assess cultural learning? What methodological problems might we encounter? If research itself is culturally bound, (how) can validity and reliability be ensured? This is obviously a very tricky area, but it seems to me that while the kind of discrete-item, objective assessment of the five savoirs advocated by Byram (1997) is a valuable attempt to specify the component factors that constitute successful intercultural communication, it is ultimately reductive, as it over-systematises what must in practice be a complex and fluctuating continuum of intercultural and interpersonal skills. This is not to say that cultural learning cannot or should not be assessed, but rather that this kind of strict componential approach needs to be tempered with more human, subjective evaluation - both from the teacher and the student him/herself (e.g. the idea of portfolio assessment). The major current issue is knowledge vs skills, both in terms of materials design and assessment. What is it that we are teaching when we teach cultural studies? And therefore, what is that we should be assessing? The methodological problems arise out of this central dichotomy: factual information is important, but only insofar as it contributes to developing appropriate skills; information is static and not an end in itself, though naturally it is what students - and teachers - will tend to focus on. The methodological challenge is to keep in view the development of cultural studies skills as overarching objectives. The problem of ensuring validity and reliability of assessment has a clear analogy in language testing. Objective testing of declarative knowledge of language systems may have very high reliability, but its validity may be questionable; conversely, integrative tests of communicative competence - performative knowledge - may have much greater validity, but may be problematic in terms of reliability. When it comes to assessing cultural learning, we are faced with very similar tensions: we may be able to test factual knowledge with a high degree of reliability but with limitations in terms of validity; while more subjective assessment of the development of cultural studies skills may have greater validity, but raises awkward - and probably unresolvable - questions in terms of reliability. The answer, in both cases, is to devise methods of assessment which take into account both kinds of learning, and marking schemes based on highly articulate sets of descriptors, which constitute a shared understanding (shared by teachers and students) of what is being tested and how it is being assessed. 11. How can/should language exams dictate the content and process of culture teaching? Can positive washback help change teachers’ attitudes to teaching culture? This raises the same question in specific terms of test design. By posing the question in terms of ‘language exams’, I mean to suggest that I am not thinking about compartmentalising cultural learning as a separate subject, but in keeping with a belief about the inter-penetration of language and culture, testing cultural learning as part and parcel of language learning. I am not sure that language exams should - or whether they can - ‘dictate what should be taught of culture in the classroom’ - or how. I do think, however, that the content and design of exams can send strong signals to teachers and students about the importance of the cultural dimension of foreign language learning, and this might be realised both at the level of testing discrete areas of cultural knowledge and in terms of more general cultural awareness. Since the context is language exams, it may be productive for exams to focus on those areas of the language (idiom, politeness markers, directness vs tentativeness etc) that are culturally specific and meaningful. 12. How can students (and teachers) be made to take the cultural dimension of foreign language teaching seriously? The feeling that culture is somehow an optional extra, which may be interesting, but which is marginal and dispensable, is very deeply inscribed in attitudes among foreign language teachers and - even very good - learners. To change such attitudes is clearly a large and challenging task, which implies long-term changes in teacher education. In the meantime, a corresponding change in exams could obviously lend official weight to the cultural dimension of foreign language teaching and, sadly, it may be the case that students will only respond to this kind of institutional pressure. Note The 12 questions discussed here were originally posed by PhD students at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest in 1997 & 1999. The answers are adapted from ‘Issues in teaching culture through language’ in Nyelvvizsga fórum: Nyelvvizsgáztatók és nyelvtanárok lapja May 2000 and from ‘Materials for cultural awareness’ in Tomlinson, B. [Ed] developing Materials for Language Teaching (Continuum 2003) References To accompany these references there is a further selected general material writing list found under Materials Development Bibliography Gillian Brown. 1990. ‘Cultural Values: the interpretation of discourse’. ELT Journal 44/1 Michael Byram. 1989. Cultural Studies and Foreign Language Education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Michael Byram. 1990. ‘Teaching culture and language towards an integrated model’. In Dieter Buttjes & Michael Byram [Eds] Mediating Languages and Cultures. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Michael Byram. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Michael Byram, Carol Morgan & colleagues. 1994. Teaching-and-learning language-and -culture. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Hugh Dellar & Darryl Hocking. 2000. Innovations. Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Hugh Dellar & Darryl Hocking. 2000. Innovations: a course in natural English. Pre-Intermediate; Intermediate; Upper Intermediate. Thomson Heinle Slavenka Drakulić. Café Europa Abacus 1996; Penguin 1999. H. Paul Grice. 1975. ‘Logic and conversation’. In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan [Eds] Syntax and Semantics Vol. 3: Speech Acts. New York, NY: Academic Press Eva Hoffman Lost in Translation: a life in a new language Heinemann 1989; Penguin 1990; Vintage 2001. Eva Hoffman. 1994. Exit into History: a journey through the new Eastern Europe London: Penguin. R. B. Kaplan. 1966. ‘Cultural thought patterns in intercultural education’. Language Learning. 16 R. B. Kaplan. 1987. ‘Cultural thought patterns revisited’. In U. Connor & R.B. Kaplan [Eds] Writing across Languages: Analysis of L2 text. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Claire Kramsch. 1993. Context and Culture in Language Teaching Oxford University Press. Robin Lakoff. 1973. ‘The logic of politeness: minding your ‘p’s and ‘q’s’. In Papers from the 9th regional meeting, Chicago Linguistics Society. Michael Lewis. 1993. The Lexical Approach. Hove: Language Teaching Publications Michael Lewis. 1997. Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting theory into practice. Hove: Language Teaching Publications Rob Pope. 1995. Textual Intervention: Critical and creative strategies for literary studies. London: Routledge. Melinda Porto. 2001. The Significance of Identity: An approach to the teaching of language and culture. La Plata, Argentina: Ediciones Al Margen/ Editorial de la Universidad de La Plata. Alan Pulverness. 2001. Changing Skies: The European course for advanced learners. Swan Communication. Viktor Shklovsky. 1917. ‘Art as Technique’. In David Lodge [Ed] Modern Criticism and Theory: A reader. Longman 1988. Leo van Lier. 1995. Introducing Language Awareness. London: Penguin Vitali Vitaliev. 1995. Little is the Light. Pocket Books. Vitali Vitaliev. 1999. Borders Up! Pocket Books. Catherine Wallace. 1992. ‘Critical literacy awareness in the EFL classroom’. In N. Fairclough [Ed] Critical language Awareness. London: Longman. Anna Wierzbicka. 1991. Cross-Cultural Pragmatics: The semantics of human interaction. New York: Mouton de Gruyer. Anna Wierzbicka. 1992. Semantics, Culture and Cognition: Universal human concepts in culture- specific configurations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Anna Wierzbicka. 1997. Understanding Cultures through their Keywords: English, Russian, Polish, German and Japanese. Oxford: Oxford University Press.