Logic software for apprenticeship in rough reasoning. In

advertisement

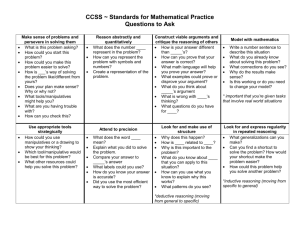

Logic Software for Apprenticeship in Rough Reasoning Bertil Rolf Blekinge Institute of Technology, School of Management SE-372 25 Ronneby, Sweden bertil.rolf@bth.se Abstract The Athena logic software packages are designed to improve on the teaching of rough reasoning procedures. Often, human actors, experts and decision makers have access only to low quality data and fallible indicators, guiding their judgment. In such situations, rough reasoning procedures will achieve better results than more elaborate reasoning procedures. Athena supports the development of rough reasoning skills via an apprenticeship method. Teaching of rough reasoning procedures can benefit from software supported apprenticeship method, integrating software use with educational games. Part I: Introduction Logic can be seen as an art of reasoning or a science of reasoning. I am here interested in arts or skills of reasoning. Arts of reasoning are forms of procedural knowledge, i.e. the mastery of arts of reasoning consists in the proper execution of the proper procedures of reasoning. Such procedures can be made the educational objective of teaching. The aims of this paper are (1) to present an integrated, software-based system of cognitive apprenticeship learning of reasoning skills. (2) To explain why such a system might be educationally effective. (3) To epistemically justify the reasoning procedures taught in “rough” domains. Part II: The Athena Apprenticeship Approach The Athena approach is a way of using logic software to support reasoning apprenticeships. We assume that reasoning skills surface and give an advantage in a peculiar type of situations. Typical of such situations is that (a) several parties possess the same data or premises but (b) the parties reach different conclusions and (c) their different conclusions rest on their different procedures for using premises to support their respective conclusion and (d) it is possible to evaluate some of these procedures as better or worse. The participants will partly agree, partly disagree about premises and conclusions. We have constructed a number of such type situations [Rol02]: Seminar: Two teams are given roles as opponent and respondent to a scientific paper, chosen by the teachers. The learning objective is to apply criteria of research quality. Panel debate: Two teams are assigned tasks as expert committees, one arguing pro the sustainability of the European Agricultural Policy, one contra. The learning objective is to understand the pros and cons of the E-CAP. Internal business decision-making: A firm is approached by a problematic customer. Should the customer be accepted or not? Teams argue pro et contra in a company setting. The learning objective is ability to mobilize, organize and communicate economic knowledge in a professional role. Business-business negotiation: Two teams are assigned roles as buyers and sellers, respectively of a software solution. The learning objective is to analyze preferences of self and opponents and managing negotiations towards an efficient frontier. City planners-business negotiation: Two teams represent a commercial developer and city planners, respectively. The learning objective is to analyze preferences of self and opponents and managing negotiations towards an efficient frontier. A glance at the learning objectives will show that reasoning skills are integrated into a wider set of professional skills, including skills of communication and social skills. This kind of courses has been given at all levels in undergraduate and postgraduate education. Instruction dominates teaching of undergraduates while common argument construction or interpretation dominates graduate teaching. In negotiations, outcome feedback on negotiated solutions can be given instantaneously, comparing teams at a class level. Student’s tasks progress towards complexity where simpler tasks are similar to the more complex. To the student, the progression in a four-week course starts by the assignment to a team. The task can be to present and defend in two weeks time a coherent stance Pro a standpoint against an opposing Con-team. One week later, the Pro-team and Con-team will switch sides. Instructions and subtasks are mainly conducted in one of our two software packages, Athena Standard or Athena Negotiator. A first day is spent on lectures and exercises analyzing or constructing arguments in the software. Feedback is given. In a second step, student teams are to build a template, representing the kinds of arguments that can be adduced in a matter. Finally, the students accommodate their templates to the standpoint to be defended. Grading and feedback is based on templates and final standpoint. Part III: The Software Packages in Education The role of the software is to facilitate the student’s grasp of the target procedures of education, to facilitate teamwork and communication between teachers and students. The reasoning procedures in preparing for oral argumentation are steered through a procedure, largely representable through graphs in the software. Fig. 1. Athena Standard (left), showing tree graph with report viewer presenting text output. Athena Negotiator (right), showing outcome diagram for two-party negotiation. The idea of the tree diagrams in the Athena Standard software is to teach students the hierarchical structure of argumentation in contrast to linear structures of presentation. Athena Standard is one of half a dozen operational software packages suitable for elementary argument analysis and argument production. Roughly half of these packages – Athena, Belvedere and Reason!Able – have been widely tested in real educational settings [Rol03], [Gel00]. All of them contain tree graphs, based on the ideas of Arne Naess or Stephen Toulmin. The role of this type of software package is to externalize procedures of logic and to cast them in a standardized form. If all students in a computer laboratory work on the same task, it is easy for a teacher to give them appropriate hints and feedback. It is easy for the student groups to experiment with different interpretations and constructions and to ask the teacher about their understanding of procedures. Team cooperation and competition between teams in oral argumentation contests help provide motivation. Specific for Athena is that the nodes of the tree graph contain large amounts of texts that can be entered by opening the node in the tree graph. By selecting a specific output report type, the user can produce handouts, position statements, full reports or comparisons of argument trees, as seen above. This facilitates various types of handouts related to various educational contests games. These games often start with presenting a position statement, supported by a handout or a memorandum. The role of the software in relation to the educational games is that the use of the software gives the students a check as to whether they are well prepared. This is accomplished by having students to build templates, which give a kind of checklists or topoi indicating which points to look for in evaluating a research article. The students hand in templates and specific preparations made for the educational games in the form of *.ath-files that are graded by the teacher. Athena Negotiator contains linear functions, producing a weighted average of the weights and values of subcomponents. The underlying theory is that of multicriteria decision analysis [Rai82], [Kee93]. Here, it is applied to two parties in negotiations. Part IV: Effectiveness of Apprenticeship An “educationally effective” system is one that is likely to produce most of the intended effects in users and few effects counter to intentions. All educational effects of reasoning software interact with the way software enters into teaching, student tasks and exams. We cannot, therefore, know about educational effects of reasoning software per se but only about the effects of educational systems of which software is a part [Rol05]. There is general evidence that educational systems based on reasoning software are more effective than systems without software [Gel00], [Hit]. Developing procedural knowledge can take two different approaches. One – the “alphabetic” approach – decomposes complex procedural knowledge into basic elements that can be combined into any complex procedure, roughly the way one can teach reading skills by first teaching letters, then words, then sentences, paragraphs, essays and books. Clearly, this kind of education is facilitated in wellaxiomatized areas where the basics and their relation to the complexes are explicitly understood. The second approach is apprenticeship models. They have been used for millennia in developing job skills, integrated into the work structure. In an apprenticeship approach, tasks presented to the learner contain most of the difficulties but in an elementary form. Subtasks or initial tasks are similar to full tasks. By learning subtasks and generalizing to full tasks on the basis of similarity, learners can be expected to learn how to manage full tasks. Reasoning apprentices are given a progression of more complex tasks similar to a tailor apprentice that starts by sowing sleeves before proceeding to more complex tasks and finally full garments. Typical of apprenticeship learning is also a form of social embedding where learners bear a social role, function or status. Tasks are not merely cognitively demanding, but their solution also put demands on social enactment. There are several characteristics of apprenticeship-guided courses. One can construct simulated real life situations for developing and exercising reasoning skills. One can use scaffolding techniques to promote collaboration within student teams and between teacher and student teams. The model of “cognitive apprenticeship” is developed to make the best of apprenticeship learning within educational institutions [Col89]. It has been tested in vocational training and professional education with positive results. Cognitive research has shown that learners of complex tasks will benefit largely from feedback directed towards user procedures, so-called “cognitive feedback”, rather than feedback related to quality of outcome [Bre94]. The cognitive apprenticeship model can be seen as a normative device for opening up target procedures and user procedures. The Athena software packages provide a standardized means of representation for problem solving. Its conceptual system facilitates easy discussion between students in the computer lab. A teacher will be able to diagnose immediately and to comment on student problem solving. Students can be given home assignment, analyzing complex scientific arguments, and deliver their solutions as files to be discussed in a class, using a computer with projector. Part V: Justification of Rough Reasoning There are limitations to argument-mapping software. The Athena-type software incorporates inferential procedures that are defensible only in special cases, e.g. when the probability of the premises is independent of one another. If inferences can run in several directions, e.g. in a Bayesian network, logic mapping software does not seem able to capture such reasoning well. Furthermore, if we have an argument from the premise A to the conclusion C, the symbolism permits the addition of an extra argument B pro/con A or C but not for or against the conditional probability P(C/A). If B says: “A is not relevant to C”, there is no way of symbolizing B. (Something of the same kind can be said for Toulmin’s argument theory where criticism of backings cannot be represented.) For these reasons, it may seem that argument-mapping software is unattractive from a stance of logical theory, even if it is educationally feasible. However, another type of epistemological justification can be given. In philosophical epistemology, reliability theories of knowledge claim that knowledge consists in such beliefs that reliably ”track” the fact they represent. In the psychology of judgment, such theories have been studied empirically since the 1950’s. The success or failure of judgment can be studied within various versions of the ”lens model” [Ham96]. The lens model assumes that we ascribe states to objects that go beyond what we directly sense. A kind of correspondence theory of truth is assumed and by ”success” or ”accuracy”, we refer to the agreement of the judged state of the object with its real state. Failure consists in non-correspondence. Any judgment relies on a number of fallible indicators or cues. These cues contain more or less information indicated by the ”ecological validity” of the cues themselves. However, the cues are seldom optimally utilized by the subject but only more or less so. Some key results about expert judgment are relevant to argument-mapping procedures. First, human expert judgment can seldom improve on linear regression models of the cues underlying judgment where regression is used to establish cue weights. Second, human experts often are inconsistent in their reliance on cues. Third, in non-deterministic domains where feedback to experts is delayed or absent, experts do not “learn from their experience”. Fourth, experts in such domains tend to a radical overconfidence about the accuracy of their judgment [Plo93]. Athena Standard and similar software packages involve a complication of the lens model by introducing hierarchies of information cues. In the lens model itself, only first order nodes, i.e. nodes of direct relevance to the conclusion, are used for an assessment. But in an argument tree, there are also nodes of the second order, third order and so on. Each node is assigned an acceptability value based on the relevance and the acceptability of each subordinate node. There are several reasons why we would expect hierarchical models to improve on non-hierarchical lens model judgment. These reasons lie not in the increased number of fine-grained cues. Instead, the software helps us select and structure such cues. Procedures towards this end, I will refer to as procedures of “rough reasoning”. My case for rough reasoning procedures relies on the fact that the accuracy of expert judgment often does not need full linear models combining weights and values of cues. There are two different, known types of simplifications in relation to full linear models. One simplification, first discovered by Robyn Dawes in the 1970’s is that we can use unit weights instead of regression based weights and still achieve a high degree of accuracy in professional judgment. Often cues correlate with one another. Unit weights are robust and generalize to new domains without the need for unrealistically large, high quality data sets, such as those demanded by regression methods [Daw88]. Another simplification is that of ”fast and frugal heuristics” in Gigerenzer’s school [Gig99]. Surprisingly simple cues can generate judgments of higher accuracy among laypersons than the accuracy of many an expert. Laypersons rely on few cues, sometimes only a single cue (“Take the best”), which correlate strongly with the state of the object. Experts try to employ several cues, each of less ecological validity, which they fail to combine properly. Both these applications of lens models show that accurate expert judgments can be had from simple models. Many experts exercise reason in domains where accessible data are bad; the collected data bear uncertain relations to the present case; causal dependencies are weak; or combinations of cues offer intricate complexity. In such cases, the maximal accuracy is low and cannot be improved by more sophisticated weighing of larger number of cues [Buc03], [Rol06]. The relevance of Athena and argument mapping to simplifications of regression lens models is as follows. First, the results of Dawes and Gigerenzer establish that simple models will often suffice to reach good accuracy of judgment. But their proposed models are different. In Dawes’ unit weight models, a possibly large number of cues are given equal weight. In Gigerenzer’s ”Take the best” model, a single cue is selected according to a lexical order. Clearly, there is a need to select which model to use in order to improve on accuracy. Second, the original lens model fits well for perceptual judgment. In perception, there is often a natural limit to the cues presented. I perceive natural objects and the validity of the cues are based on induction over natural kinds. But professional inductive judgment is more problematic than perceptually based judgment. Say a schoolteacher wants to predict the success of a 15 year-old student. There is a myriad of facts available to the teacher. The facts have no obvious internal structure. Some are biological, some social, some related to previous school work, some related to the school class. Some cues are specific for the students, others general. Cues that had predictive strength ten years ago need not be valid today. The Athena Standard type of software can represent different lens models. Cues can be selected, ordered, assessed and filtered. If we assign weights and values in one way in Athena, a Dawesian unit weight model results. If we do it in another way, one of Gigerenzer’s models results. Thus selected and sorted, the cues would form a lens model with relevance weights and acceptability values assigned. Hence, there are domains where the accuracy of expert judgments obtained by rough reasoning cannot be improved. Although the most accurate lens model that is reached after rough reasoning in Athena in such a domain is simple per se, the rough reasoning procedures used to select the model may be complex, obscure or counterintuitive. In such domains, rough reasoning procedures, supported by Athena-type logic software will be the best general procedures that are humanly possible. References [Bre94] [Buc03] [Col89] [Daw88] [Gel00] [Gig99] [Ham96] Brehmer, B. The Psychology of Linear Judgment Models. Acta Psychologica 87, 137-154, 1994. Buckingham Shum, S. The Roots of Computer Supported Argument Visualization. In: Visualizing Argumentation. Software Tools for Collaborative and Educational Sense-Making (Kirschner, P. et al. (Ed)), 3-24. Springer, London, 2003. Collins, A. et al. Cognitive Apprenticeship. Teaching the Crafts of Reading, Writing, and Mathematics. In: Knowing, Learning, and Instruction (Resnick, L. (Ed)), 453-494. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 1989. Dawes, R. Rational Choice in an Uncertain World. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Orlando, FL, 1988. van Gelder, T. The Efficacy of Undergraduate Critical Thinking Courses. A Survey in Progress. http://www.philosophy.unimelb.edu.au/reason/papers/efficacy.html, 2000. Gigerenzer, G. et al. Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999. Hammond, K. Human Judgment and Social Policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996. [Hit] [Kee93] [Plo93] [Rai82] [Rol02] [Rol03] [Rol05] [Rol06] Hitchcock, D. The Effectiveness of Computer-Assisted Instruction in Critical Thinking. In: Informal Logic (forthcoming). Keeney, R. et al. Decisions with Multiple Objectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993. Plous, S. The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1993. Raiffa, H. The Art and Science of Negotiations. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1982. Rolf, B. Athena Software. http://www.athenasoft.org, 2002. Rolf, B. et al. Developing the Art of Argumentation. A Software Approach. In: Proceedings of the 5th Conference of the ISSA (van Eemeren, F. et al. (Eds.)), 919-925. Sic Sat, Amsterdam, 2003. Rolf, B. Testing Reasoning Software. A Bayesian Way. In: Computing, Philosophy, and Cognitive Science (Dodig-Crnkovic, G. et al. (Eds)). Cambridge Scholars Press, Cambridge (forthcoming). Rolf, B. Decision Support Tools and Two Types of Uncertainty Reduction. In: Effective Environmental Assessment Tools – Critical Reflections on Concepts and Practice (Emmelin, L. (Ed.)), 134-157. Blekinge Institute of Technology, Report 2006:3 from the MISTProgramme. Acknowledgments. This work has been granted support from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. A previous version has benefited from comments by C. C. Rolf.