Assessing and Facilitating Text Comprehension Problems, Carol E

advertisement

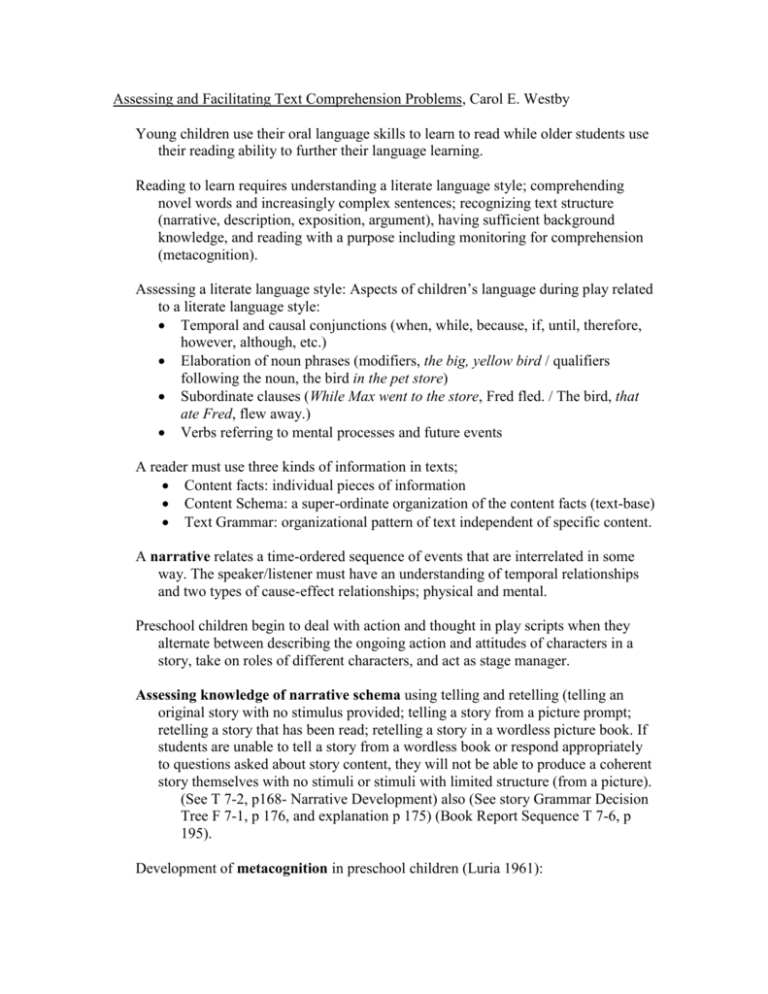

Assessing and Facilitating Text Comprehension Problems, Carol E. Westby Young children use their oral language skills to learn to read while older students use their reading ability to further their language learning. Reading to learn requires understanding a literate language style; comprehending novel words and increasingly complex sentences; recognizing text structure (narrative, description, exposition, argument), having sufficient background knowledge, and reading with a purpose including monitoring for comprehension (metacognition). Assessing a literate language style: Aspects of children’s language during play related to a literate language style: Temporal and causal conjunctions (when, while, because, if, until, therefore, however, although, etc.) Elaboration of noun phrases (modifiers, the big, yellow bird / qualifiers following the noun, the bird in the pet store) Subordinate clauses (While Max went to the store, Fred fled. / The bird, that ate Fred, flew away.) Verbs referring to mental processes and future events A reader must use three kinds of information in texts; Content facts: individual pieces of information Content Schema: a super-ordinate organization of the content facts (text-base) Text Grammar: organizational pattern of text independent of specific content. A narrative relates a time-ordered sequence of events that are interrelated in some way. The speaker/listener must have an understanding of temporal relationships and two types of cause-effect relationships; physical and mental. Preschool children begin to deal with action and thought in play scripts when they alternate between describing the ongoing action and attitudes of characters in a story, take on roles of different characters, and act as stage manager. Assessing knowledge of narrative schema using telling and retelling (telling an original story with no stimulus provided; telling a story from a picture prompt; retelling a story that has been read; retelling a story in a wordless picture book. If students are unable to tell a story from a wordless book or respond appropriately to questions asked about story content, they will not be able to produce a coherent story themselves with no stimuli or stimuli with limited structure (from a picture). (See T 7-2, p168- Narrative Development) also (See story Grammar Decision Tree F 7-1, p 176, and explanation p 175) (Book Report Sequence T 7-6, p 195). Development of metacognition in preschool children (Luria 1961): Children between 2 ½ and 4 years can use their own speech both to initiate and to inhibit their actions. Planning and understanding plans is a critical dimension for reading comprehension of mental cause-effect relationships: Awareness of when and how to plan is critical for understanding characters’ goal-directed behavior in narratives. Ability to comprehend the theme of a story requires that we figure out a character’s plans and goals (perspective taking- knowing what others are seeing). Understanding plans is essential in understanding the purpose or goal behind written text. The ability to understand plans is a complex inferential act that develops slowly over time. Think Aloud Curriculum: Ralf the Bear Posters model the steps in self guiding speech: What is my problem? Or What am I supposed to do? How can I do it? Or What’s my plan? Am I using my plan? How did I do? Stages of Planning in Pretend Play: Symbolic pretend play has a number of components including: Increasing decontextualization- decreased reliance on concrete props and increased reliance on verbal coding Moving from representing highly familiar themes to unfamiliar, novel themes Increasing organization and preplanning Increasing ability to engage in role taking A Developmental Sequence in Organizing and Planning: 17- 19 Months: The child moves quickly from one instance of pretending to another with no links between events and little elaboration. 19 Months to 2 Years: Children begin to combine related objects in play (show an awareness that things go together. 2 – 3 Years: Children elaborate familiar schema (will gather many items needed for pretend play- dishes, cups, spoons, etc. to feed baby). 3 – 4 Years: Children produce an evolving sequence of events along with running commentary announcing completed actions. Activities are not directly planned but follow logically from the schema (prepare food, set table, feed baby, clean up). 4 Years: Children plan their play in advance and the planning phase may take longer than the actual pretend play. They announce what they are going to play. 5 Years: Children plan their own and others roles and they monitor what other children are doing. Normally developing children have well developed symbolic play by age 5-6. Older students with language impairments exhibit deficits in many aspects of symbolic representation that develop during the preschool years. Many middle school students with LD so not exhibit the sequential organization of play that is present in normal 3-year olds’ play. Pellegrini (1985) reported that children who exhibit higher levels of symbolic pretend play also exhibit more literate language styles (more adjectives, conjunctions, words referring to metacognitive functions (I think, I know), and more endophoric as opposed to exophoric references (text related rather than context related- decontextualized language). One can also investigate students’ planning abilities by presenting them with hypothetical problems (Jim has been playing with the truck all morning and now Fred wants to play with it. What can Fred do or say to get Jim to share the truck?). Spivack, Plat and Shure (1976) reported that well adjusted 4 and 5 year old children were able to give more alternative solutions to personal problems and could give more causes and consequences for the problems than poorly adjusted children. Student responses are scored for number of plans, number of steps in a plan, if a justification for the plan is provided, the feasibility of the plan(s). Meacham (1979) explored the development of preschool children’s use of language to guide motor activity: 1st Stage: children accompany motor activity with verbal activity but they are independent. nd 2 Stage: Verbal activity describes the outcome of motor activity. Language follows the activity and restates the events but does not fulfill a guiding role to initiate or direct the motor activity. 3rd Stage: Language is used to describe the goals of the motor activity. By describing the goal the child is better able to remember it making it possible to compare the actual outcome with the goal; that is, to evaluate the outcome th 4 Stage: Language precedes the activity and plays a major role in planning and guiding the activity. Until children use language to plan and control their behavior, they will not develop awareness of cognitive processes or a theory of mind (mental states exist and are not the same as external acts or eventsdevelops between ages 3-7). (See t 7-3, p 179). Knowledge of Cognition: Any work related to metacognitive monitoring of comprehension and performance of academic tasks is based on first understanding the concepts of knowing, remembering, forgetting, and guessing (typically developed by age 7). Book Sharing: Wells (1986) documented that the amount children were read to during the preschool years was the language variable most related to academic success in fifth grade. Families of RD children sometimes report having tried to read stories to their children, but the children were uninterested or inattentive so the family did not pursue the activity. If books are carefully matched to the child’s narrative comprehension level, however, nearly every child will enjoy listening to stories. Hierarchy of Questions/ Comments to use with a 2-4 year old Child: Item Levels (What’s that? Who’s that?) Item Elaboration (How many pigs? What color cat?) Event (What happened? What’s _____ doing?) Motive / Cause (Why did he want an umbrella) Evaluation / Reaction (How did he feel when that happened? Was that a bad thing to do?) Real-World Relevance (The pig’s taking a bath. You did that this morning.)