Chapter 9 - Materiality and Risk

advertisement

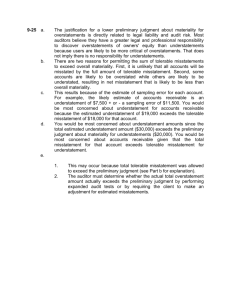

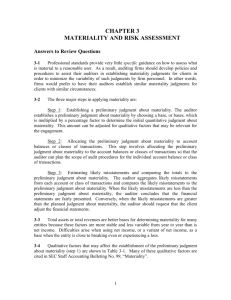

Chapter 9 - Materiality and Risk Multiple Choice Questions From CPA Examinations 9-22 a. (4) b. (4) 9-23 a. (1) b. (1) c. (1) 9-24 a. (2) b. (3) c. (1) 9-25 a. b. c. d. The justification for a lower preliminary judgment about materiality for overstatements is directly related to legal liability and audit risk. Most auditors believe they have a greater legal and professional responsibility to discover overstatements of owners' equity than understatements because users are likely to be more critical of overstatements. That does not imply there is no responsibility for understatements. There are two reasons for permitting the sum of tolerable misstatements to exceed overall materiality. First, it is unlikely that all accounts will be misstated by the full amount of tolerable misstatement. Second, some accounts are likely to be overstated while others are likely to be understated, resulting in net misstatement that is likely to be less than overall materiality. This results because of the estimate of sampling error for each account. For example, the likely estimate of accounts receivable is an understatement of $7,500 + or - a sampling error of $11,500. You would be most concerned about understatement for accounts receivable because the estimated understatement of $19,000 exceeds the tolerable misstatement of $18,000 for that account. You would be most concerned about understatement amounts since the total estimated understatement amount ($30,000) exceeds the preliminary judgment about materiality for understatements ($20,000). You would be most concerned about accounts receivable given that the total misstatement for that account exceeds tolerable misstatement for understatement. e. 1. 2. This may occur because total tolerable misstatement was allowed to exceed the preliminary judgment (see Part b for explanation). The auditor must determine whether the actual total overstatement amount actually exceeds the preliminary judgment by performing expanded audit tests or by requiring the client to make an adjustment for estimated misstatements. 9-26 a. The profession has not established clear-cut guidelines as to the appropriate preliminary estimates of materiality. These are matters of the auditor's professional judgment. To illustrate, the application of the illustrative materiality guidelines shown in Figure 9-2 (page 235), are used for the problem. Other guidelines may be equally acceptable. STATEMENT COMPONENT Earnings from continuing operations before taxes Current assets Current liabilities Total assets b. c. d. PERCENT GUIDELINES 5 - 10% 5 - 10% 5 - 10% 3 - 6% DOLLAR RANGE (IN MILLIONS) $20.9 $112.7 $ 60.7 $115.8 - $ 41.8 - $225.4 - $121.5 - $231.6 The allocation to the individual accounts is not shown. The difficulty of the allocation is far more important than the actual allocation. There are several ways the allocation could be done. The most likely way would be to allocate only on the basis of the balance sheet rather than the income statement. Even then the allocation could vary significantly. One way would be to allocate the same amount to each of the balance sheet accounts on the consolidated statement of financial position. Using a materiality limit of $21,000,000 before taxes (because it is the most restrictive) and the same dollar allocation to each account excluding retained earnings, the allocation would be approximately $1,000,000 to each account. There are 21 account summaries included in the statement of financial position, which is divided into $21,000,000. An alternative is to assume an equal percentage misstatement in each of the accounts. Doing it in that manner, total assets should be added to total liabilities and owners' equity, less retained earnings. The allocation would be then done on a percentage basis. Auditors generally use before tax net earnings instead of after tax net earnings to develop a preliminary judgment about materiality given that transactions and accounts being audited within a segment are presented in the accounting records on a pretax basis. Auditors generally project total misstatements for a segment and accumulate all projected total misstatements across segments on a pretax basis and then compute the tax effect on an aggregate basis to determine the effects on after tax net earnings. By allocating 75% of the preliminary estimate to accounts receivable, inventories, and accounts payable, there is far less materiality to be allocated to all other accounts. Given the total dollar value of those accounts, that may be a reasonable allocation. The effect of such an allocation would be that the auditor might be able to accumulate sufficient competent evidence with less total effort than would be necessary under part b. Under part b, it would likely be necessary to audit, on a 100% basis, accounts receivable, inventories, and accounts payable. On most audits it would be expensive to do that much testing in those three accounts. 9-26, continued e. 9-27 It would likely be necessary to audit accounts such as cash and temporary investments on a 100% basis. That would not be costly on most audits because the effort to do so would be small compared to the cost of auditing receivables, inventories, and accounts payable. It is necessary for you to be satisfied that the actual estimate of misstatements is less than the preliminary judgment about materiality for all of the bases. First you would reevaluate the preliminary judgment for earnings. Assuming no change is considered appropriate, you would likely require an adjusting entry or an expansion of certain audit tests. a. The following terms are audit planning decisions requiring professional judgment: Preliminary judgment about materiality Acceptable audit risk Tolerable misstatement Inherent risk Risk of fraud Control risk Planned detection risk b. The following terms are audit conclusions resulting from application of audit procedures and requiring professional judgment: Estimate of the combined misstatements Estimated total misstatement in a segment c. It is acceptable to change any of the factors affecting audit planning decisions at any time in the audit. The planning process begins before the audit starts and continues throughout the engagement. 9-28 Acceptable audit risk is a measure of how willing the auditor is to accept that the financial statements may be materially misstated after the audit is completed and an unqualified opinion has been issued. a. True. A CPA firm should attempt to use reasonable uniformity from audit to audit when circumstances are similar. The only reasons for having a different audit risk in these circumstances are the lack of consistency within the firm, different audit risk preferences for different auditors, and difficulties of measuring audit risk. b. True. Users who rely heavily upon the financial statements need more reliable information than those who do not place heavy reliance on the financial statements. To protect those users, the auditor needs to be reasonably assured that the financial statements are fairly stated. That is equivalent to stating that acceptable audit risk is lower. Consistent with that conclusion, the auditor is also likely to face greatest legal exposure in situations where external users rely heavily upon the statements. Therefore, the auditor should be more certain that the financial statements are correctly stated. c. True. The reasoning for c is essentially the same as for b. d. True. The audit opinion issued by different auditors conveys the same meaning regardless of who signs the report. Users cannot be expected to evaluate whether different auditors take different risk levels. Therefore, for a given set of circumstances, every CPA firm should attempt to obtain approximately the same audit risk. 9-29 a. b. c. 9-30 False. The acceptable audit risk, inherent risk, or control risk may all be different. A change of any of these factors will cause a change in audit evidence accumulated. False. Inherent risk and control risk may be different. Even if acceptable audit risk is the same, inherent risk and control risk will cause audit evidence accumulation to be different. True. These are the primary factors determining the evidence that should be accumulated. Even in those circumstances, however, different auditors may choose to approach the evidence accumulation differently. For example, one firm may choose to emphasize analytical procedures, whereas other firms may emphasize tests of controls. a. 1. 2. The auditor may set inherent risk at 100% because of lack of prior year information. If the auditor believes there is a reasonable chance of a material misstatement, 100% inherent risk is appropriate. Similarly, because the auditor does not plan to test internal controls due to the ineffectiveness of internal controls, a 100% risk is appropriate for control risk. Acceptable audit risk and planned detection risk will be identical. Using the formula: PDR = AAR / (IR x CR), if IR and CR equal 1, then PDR = AAR. 3. If planned detection risk is lower, the auditor must accumulate more audit evidence than if planned detection risk is higher. The reason is that the auditor is willing to take only a small risk that substantive audit tests will fail to uncover existing misstatements in the financial statements. 1. The auditor should be conservative in estimates of the likelihood of misstatements in the financial statements, because the costs of being wrong are relatively high. It would be inappropriate for auditors to set low levels of inherent and control risk without doing substantive testing to determine if the financial statements are actually misstated. b. For example, using the formula of the audit risk model shown in part a, assume inherent and control risk are each set at 20% and acceptable audit risk is 4%. Using the formula, planned detection risk would be equal to 100%. Therefore, no substantive audit testing would be necessary. That is inconsistent with the responsibilities of the auditor. Therefore, relatively high inherent and control risk are used even under the most ideal circumstances. Furthermore, given that internal control effectiveness is often dependent on the performance of procedures performed by employees who may be prone to errors or management override, control risk cannot be set too low. 9-30 (continued) 2. 3. Using the formula in a., planned detection risk is equal to 20% [PDR = .05 / (.5 x .5) = .2]. Less evidence accumulation is necessary in b-2 than if planned detection risk were smaller. Comparing b-2 to a-2 for an acceptable audit risk of 5%, considerably less evidence would be required for b-2 than for a-2. c. 1. 2. 3. 9-31 The auditor might set acceptable audit risk high because Redwood City is in relatively good financial condition and there are few users of financial statements. It is common in municipal audits for the only major users of the financial statements to be state agencies who only look at them for reasonableness. Inherent risk might be set low because of good results in prior year audits and no audit areas where there is a high expectation of misstatement. Control risk would normally be set low because of effective internal controls in the past, and continued expectation of good controls in the current year. Using the formula in a-2, PDR = .05 / (.2 x .2) = 1.25. Planned detection risk is equal to more than 100% in this case. No evidence would be necessary in this case, because there is a planned detection risk of more than 100%. The reason for the need for no evidence is likely to be the immateriality of repairs and maintenance, and the effectiveness of internal controls. The auditor would normally still do some analytical procedures, but if those are effective, no additional testing is needed. It is common for auditors to use a 100% planned detection risk for smaller account balances. It would ordinarily be inappropriate to use such a planned detection risk in a material account such as accounts receivable or fixed assets. a. Acceptable audit risk A measure of how willing the auditor is to accept that the financial statements may be materially misstated after the audit is completed and an unqualified opinion has been issued. This is the risk that the auditor will give an incorrect audit opinion. Inherent risk A measure of the auditor's assessment of the likelihood that there are material misstatements in a segment before considering the effectiveness of internal control. This risk relates to the auditor's expectation of misstatements in the financial statements, ignoring internal control. Control risk A measure of the auditor's assessment of the likelihood that misstatements exceeding a tolerable amount in a segment will not be prevented or detected by the client's internal controls. This risk is related to the effectiveness of a client's internal controls. Planned detection risk A measure of the risk that audit evidence for a segment will fail to detect misstatements exceeding a tolerable amount, should such misstatements exist. In audit planning, this risk is determined by using the other three factors in the risk model using the formula PDR = AAR / (IR x CR). 9-31 (continued) b. Acceptable Audit Risk IR x CR PDR = AAR / (IR x CR) Planned Detection Risk in percent 1 .05 1.00 .05 2 .05 .24 .208 3 .05 .24 .208 4 .05 .06 .833 5 .01 1.00 .01 6 .01 .24 .042 5% 20.8% 20.8% 83.3% 1% 4.2% c. 1. 2. 3. 4. Decrease; Compare the change from situation 1 to 5. Increase; Compare the change from situation 1 to 2. Increase; Compare the change from situation 1 to 2. No effect; Compare the change from situation 2 to 3. d. Situation 5 will require the greatest amount of evidence because the planned detection risk is smallest. Situation 4 will require the least amount of evidence because the planned detection risk is highest. In comparing those two extremes, notice that acceptable audit risk is lower for situation 5, and both control and inherent risk are considerably higher.