rainfall prediction, management and utilization for crop

advertisement

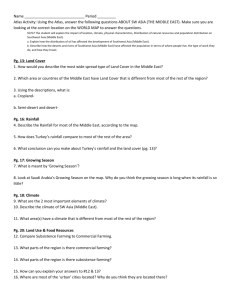

RAINFALL PREDICTION, MANAGEMENT AND UTILIZATION FOR CROP PRODUCTION IN CONSERVATION AGRICULTURE PLOTS AT SHEWULA M. Mlipha Department of Geography, Environmental Science and Planning Faculty of Science University of Swaziland P/Bag 4 Kwaluseni Swaziland Tel. +268 518 4011 Fax. +268 518 5276 Email. Mlipha@science.uniswa.sz ABSTRACT Crop production, particularly maize, in Swaziland is practised almost exclusively under rain-fed conditions yet a crippling drought is currently afflicting the country. The effects of the drought are particularly severe in the rural areas manifested in the chronic shortage of food supply. The community of Shewula is experiencing persistent drought spells which pose a serious threat to rural sources of livelihood, particularly agriculture. It is essential for farmers to have a sound understanding of rainfall pattern as well as rainfall prediction systems. Moreover, the meagre rainfall that occurs needs to be managed and utilized efficiently to produce food crops. The study aimed at documenting the ways farmers predict rainfall utilizing their indigenous knowledge; the strategies adopted by farmers to cope with the persistent drought and the various mechanisms of improving the moisture retention capacity their soil. The study sought to establish the perspective of the farmers involved in conservation agriculture on the mentioned issues. Information was solicited from the farmers through key informant and structured interviews. Several indigenous techniques of rainfall prediction have been presented where the farmers relied on natural phenomena to predict rainfall occurrence. The study established that the farmers attach a higher level of trust and confidence on the indigenous ways of rainfall prediction than the conventional ones. This is due to lack of access to the media disseminating conventional weather prediction reports. The study noted the need to improve farmers’ accessibility to media disseminating conventional weather prediction reports as well as investigate ways of mainstreaming indigenous knowledge systems of weather prediction. The study also identified various strategies adopted by the farmers to cope with the persistent drought. The study established that the drought has influenced changes in the farming calendar of the area. Notably, the farming season now starts at around November or December instead of August or September. Moreover, farmers showed reliance on indigenous crops which are viewed as more drought tolerant than some of the hybrid seed they have encountered. Various mechanisms of improving moisture retention capacity of the soil were identified. These mechanisms are inherent in conservation agriculture and they include retention of crop residue to accumulate as soil cover, intercropping, building of terraces and others. It could be concluded that conservation agriculture seems to presents the Shewula community with a sustainable way of producing their food crops particularly in the prevailing dry conditions. INTRODUCTION Almost all food production in Swaziland depends on rainfall yet the country is currently experiencing persistent drought characterized by below average rainfall that is also unreliable. This rainfall situation has serious implications on subsistence crop farming which supports the livelihoods of the rural population constituting approximately 70 percent of the Swazi population Central Statistical Office, 1997). The rural households may be able to cope with the shock of a single dry season and recover to normal food supply situations when the rains return. However, the cumulative effect of consecutive dry seasons may push some households into chronic food insecurity and even destitution. The community of Shewula has been subjected to persistent drought year after year and the toll is beginning to show in terms of the chronic food shortages the community is experiencing. Irrigation is usually used to grow crops in areas where rainfall is insufficient to meet crop water needs. Irrigation is possible under well-watered conditions and in areas with a sound economic footing as irrigation tends to be fairly expensive. Shewula is not endowed with any significant flowing streams to sustain an irrigation scheme adequate to benefit the entire community. Moreover, the people of Shewula are too poor to afford an irrigation scheme of any sort. Adoption of appropriate farming strategies to cope with rainfall deficits and unreliability is essential. Moreover, farmers need to develop a sound understanding of the rainfall patterns while enhancing their local knowledge on rainfall prediction. The community need to manage the rainfall season in such a way that the little rainfall available is utilized efficiently to the benefit of the crops. The study seeks to answer the following questions which also form the basic objectives of the study: How do farmers predict the incidence of rainfall outside existing conventional systems? What is the influence of the rainfall pattern on the farming calendar among farmers at Shewula? What farming strategies have farmers adopted to cope with deficient and unreliable rainfall? How have the farmers attempted to improve the moisture retention capacity of the land? The study will be based at Shewula a rural settlement situated in the north-eastern part of Swaziland, approximately at the border separating Swaziland and Mozambique. It is situated on the Lubombo plateau at approximately 300 – 500 metres above sea level. Shewula experiences persistent drought spells which have adverse effects on production of food crops such as maize. Maize, being a staple crop, is grown on wide scale although the yields are continuously declining due to several factors including the area being drought prone, lack of cattle (for animal traction), scarcity of tractors for hire, limited access to agricultural inputs and others (Mlipha, 2004). Other crops grown include sorghum, beans, jugo beans and other traditional crops albeit on a minor scale. Moreover, the community also practises a limited range of non-food income earning activities to supplement food supply and income. The major activity is the conservancy facility, the Shewula Mountain Camp, run by the community members as a business venture employing a number of local men and women. LITERATURE REVIEW Crop production, particularly maize, is practiced almost exclusively under rain-fed conditions in most of southern African countries. The late on-set of the rainy season (lasting from mid – October to April) as well as the continuing poor and erratic rains are causing concern about overall crop production and food security in most parts of southern Africa. The seasonal rains in southern Africa are currently below normal compared to long-term regional average. In Swaziland, the combination of below normal rains and large moisture deficits in the last decade is causing severe drought conditions and increasing concern of reduced crop yield and continued food insecurity in the2004/2005 season. The inconsistent and late rainfall, high costs of agricultural inputs and impacts of HIV/AIDS are responsible for the bleak food security situation in the country. A state of emergency was declared by Government of Swaziland in view of the bleak food security situation and the on-going drought. The need for improvements in rainfall prediction systems under the prevailing rainfall situation can not be overemphasized. The Department of Meteorological Services has made tremendous efforts in improving its weather and climate prediction capacity through acquisition of modern technology and equipment. This is all done to enhance the accuracy and reliability of meteorological data collected and disseminated. What may need to be ascertained is the accessibility of this data to the small scale subsistence farmers on Swazi Nation Land (SNL). There is also a need to investigate the confidence level rural farmers attached to rainfall data generated by the Department of Meteorological Services as well as how they access this data. Weather information is usually communicated through both print and electronic media on daily basis. Despite the services of the Department of Meteorological Services some farmers in the rural areas still depend on their local knowledge to predict the rainfall situation in their areas. The use of modern generated prediction systems has made little in-roads in some small scale farmers in the rural areas. The failure of modern technology to have an impact in local development has been cited in other areas (ETC Foundation, 1994). Elsewhere, the failure of local development initiatives has been attributed to neglect of indigenous knowledge (Osunade, 1994). Hence the capturing and documentation of indigenous knowledge has been found to be vital (IUCN, 1995, Matowanyika, 1999, Fakudze, 2001). There have also been suggestions for the incorporation of indigenous knowledge systems into modern technology to facilitate understanding and utilization of available modern techniques (LORE, 1992 & Osunade, 1994). The SADC-ELMS and The World Conservation Union (IUCN) set the tone in the recognition of the importance of indigenous knowledge particularly in environmental resource management. In response SADC countries produced documents of indigenous knowledge systems in various areas of national development. Indigenous ways of predicting rainfall were studied and documented by Fakudze (1998 and 2001), Manyatsi, & Kasanene, 1993 and others which were mostly traditional and religious-based as well as making reference to certain features of the environment. Quite noticeable in the documents is the existence of many ways of predicting rainfall which also vary according to regions and communities (Fakudze, 1998). However, the studies did not venture into the estimation of the reliability and accuracy of the local rainfall prediction approaches as well as the level of confidence and trust farmers have placed on the indigenous ways of rainfall prediction. Indigenous knowledge seems to be on the verge of disappearing judging by the hesitation in the acceptance of its value in terms of capacity to solve existing problems (Mavimbela, 2004 & Matowanyika, 1996). Caution must be exercised not to romanticise indigenous rainfall prediction knowledge without putting it to test. Its accuracy and reliability needs to be proven before it could be integrated into mainstream rainfall prediction systems. The test must beginning with ascertaining the amount of faith and recognition farmers attach to indigenous rainfall prediction systems. The risk of extinction of indigenous knowledge is also due to lack of recognition and support from the formal sector; competition with modern technology which has led its isolation; modernization and external socio-cultural influences (Warren & Slikkerveer, 1995; IUCN, 1995 & Mavimbela, 2004. It is important for rainfall prediction systems to always strive for accuracy and reliability to minimize risk and uncertainty among farmers. Equally important is how the farmers manage and utilize the available rainfall for crop production. The available rainfall, as little as it may be, needs to be used as efficiently as possible in crop production. Farmers’ response to adverse rainfall situations have included early crop planting to benefit from the soil moisture associated with the first rains. Some farmers practice intercropping to minimize the risk of depending on one crop in case it is affected by drought. Moreover, some farmers focus on cultivation of early maturing and drought resistant hybrid seed and other techniques. These farming strategies have associated problems under the current rainfall situation in the country. For instance, early planting has failed to have a positive impact on crop production because of the persistent failure of the early rainfall. Intercropping, currently done indiscriminately, has led to poor crop performance due to competition for soil moisture among the crops while hybrid seed, especially maize, is not favoured by the local farmers as it is believed to be lighter and less tasty than indigenous maize. The problems stated above may be adequate to necessitate farmers to adopt other farming strategies to respond to the erratic rainfall and persistent drought. It is, therefore, of utmost importance that the study identifies the farming strategies currently being practiced by the farmers in view of the problems associated with the mentioned strategies and general problem of persistent drought. Quite recently Swazi farmers have been introduced to conservation agriculture, particularly in the dry areas. Shewula is one of the areas in Swaziland that has benefited from an FAO/COSPE project aimed at teaching farmers about conservation agriculture to stimulate farmers to adopt it as a strategy to cope with the persistent drought (Mlipha, 2004 & COSPE/Government of Swaziland, 2005). Conservation Agriculture assumes a number of names in the various contexts of its application in the world. It is referred to as conservation farming in some parts of the world while in the Americas; it is commonly referred to zero or no tillage (Landers, undated). Whatever its reference, conservation agriculture emerged as farmers shift from the destructive farming methods associated with conventional agriculture to more productive, efficient and environmentally friendly ways of farming. Conservation agriculture has to do with minimum tillage to grow crops while practising intercropping and crop rotation including planting of leguminous crops to improve soil structure and quality (Derspsch, 1998). . METHODOLOGY The study focused on farmers practising conservation agriculture at Shewula. Since conservation agriculture is still at its infancy stage at Shewula, very few farmers have adopted it to date. Therefore, the study dealt with a very small population of seven farmers. Ten farmers have received training on conservation agriculture to date and only seven practised conservation agriculture in the 2004/05 farming season. Sampling was, therefore, unnecessary owing to the small population being studied. Two methods of data collection were utilized in the study both based on face-to-face interviews: structured interviews and key informants. Both methods are said to be essential when dealing with a small population (Ellis, 2000). It is also imperative for data collection to rely on more than one data collection technique to enhance complementarity within the overall research (Ellis, 2000; Woodhouse, 1998 & Moser, 1996). Key Informants Two male elders in the community were selected to be key informants based on their age as well as being farmers of repute in the community. The key informants, however, are not practising conservation agriculture. An open ended and unstructured interview was conducted with them where the data was captured using a voice recorder (permission to record was granted by the informants). The interviews covered a wide range of topics related to rainfall prediction and farming strategies responding to persistent drought situations. Structured Interviews All the seven farmers already practising conservation agriculture were respondents of the study. An interview guide (similar to a questionnaire) was used to solicit information from the respondents (Appendix 1). Information acquired pertained to: Indigenous rainfall prediction systems. Access to meteorological data. Period of cultivation in view of delayed rainfall. Farming strategies to cope with prolonged drought conditions. Farmers’ knowledge in the estimation of crop water demand. Crop grown during the dry and rainy conditions. Methods of improving soil moisture retention capacity. Factors constraining irrigation at Shewula. The information gathered was recorded in the interview guides and separate paper was made available to record detailed responses and incidental data. Building of trust between researchers and the respondents is cited as crucial in data collection especially when soliciting sensitive data dealing with incomes and techniques of doing things (Ellis, 2000). To achieve the respondents’ trust a resident of the area, involved in conservation agriculture (research coordinator), was engaged to accompany the researcher when visiting all the respondents and key informants’ homesteads. Data Analysis The data collect was qualitative composed of statements of opinion and ideas. The fact that the population was also small did not require any elaborate data analysis techniques. Only selection of relevant data was conducted. The data found relevant was presented as statements in tables and boxes. RESULTS AND DISCUSION The results are presented according the study questions which formed the subheads guiding the presentation of the results. The heads derived from the study questions are: Indigenous ways of predicting rainfall; Strategies farmers have adopted to cope with the persistent drought; mechanisms of improving moisture capacity of the land under conservation agriculture. Rainfall Prediction Techniques Farmers practising conservation agriculture seem to rely exclusively on indigenous ways of predicting rainfall. Of the ten farmers interviewed only one relied on the radio for rainfall prediction. In the prediction of rainfall they use natural or environmental phenomena including clouds, animals, vegetation, rocks, wind, temperatures and the moon. Table 1 shows a list of farmers’ rainfall prediction techniques. Table 1. Rainfall Prediction Techniques of Farmers Involved in Conservation Agriculture at Shewula. Phenomena Trees Description Mncwaphe tree usally fruits inabundance when rainfall is going to be heavy on that year. Moreover, a majority of trees flower early in the summer season if rainfall is going to be normal. The moon and sun The moon when facing downwards at its first and last quarter indicates good rainfall as well as when there is a circle around the moon and the sun. In SiSwati they say iyacitsa meaning that the moon is pouring water when it is in mentioned position. Winds When easterly wind meets with westerly wind there is definitely going to be rainfall. Likewise when warm winds are experienced to be followed by cool wind rainfall occurs. Numerous small whirl winds (tishingishane) also indicate imminent rainfall. Animals Once a tortoise or frog begins to make endless sounds in its habitat, rainfall usually occurs. Birds: The arrival of the migratory black swallows (emahlolamvula) coincides with the arrival of rainfall. There is a bird which makes a coo sound signalling the arrival of rainfall. Temperatures High temperatures in the summer seasons are often followed by rainfall. The first (imbotisamahlanga) rainfall This rainfall proceeds the farming season. If it occurs on time around end of July means the rainfall situation will be good for farming. Imbotisamahlanga implies a rainfall that occurs to facilitate the rotting of maize stalks. Clouds Building up and accumulation of clouds is always associated with imminent rainfall. Rocks Rocks on cliff faces often “sweat” and water filter off the rocks and flow down the face of the cliff sometimes assisted by indigenous trees such as manono, tikhwelamfene and sphakuhlo. The amount of rainfall to be received is estimated by the amount of “sweat” the rocks emit. Plenty of “sweat” implies heavy rainfall and minor “sweat” signals a drizzle. If what is mentioned in Table 1 does not occur or the opposite occur usually that signals drought. The reliance on natural phenomena for rainfall prediction is interesting as opposed to the cultural divine beliefs associated with rainfall making (Kasanene, 1993). The findings of the study demonstrate that rainfall prediction techniques vary from person to person. The more senior people (key informants) who are above seventy five years old use different techniques (Box 1) to those of the than relatively younger farmers whose ages ranged between late twenties to late forties. Others, however, noted that weather prediction techniques tend to vary according regions and places of domicile (Fakudze, 1998). Moreover, the rainfall prediction techniques in Table 1 are fundamentally similar to those presented by Osunade (1994), Fakudze (1998) and Manyatsi, 2001). The only different new techniques include the use of rock and whirl winds which were mentioned by the key informants at Shewula. Most of the studies on indigenous rainfall prediction systems do not say much about the reliability and accuracy of the systems. Apparently, the assessment of the reliability and accuracy of rainfall prediction systems is a mammoth task in the absence of an appropriate scientific tool of assessment. Moreover, the study noted that the concern is not necessarily reliability and accuracy but is the trust people put on the indigenous rainfall prediction systems. They seem to attach more trust to their own ways of weather prediction than the conventional means prediction. Meteorological weather reports are making little impact in the lives of rural farmers mainly because of access problem as well as difficulties farmers encounter when trying to understand meteorological data. The weather forecast disseminated through the radio is accused of being lacking in specific details on the local areas. According to the farmers, the radio gives a general and the barest summary of national weather conditions such as “it will be partly cloudy with drizzle in higher places”. To the farmers at Shewula such weather prediction approach is always not reflective of the conditions that finally prevail in their area. More detailed and graphic predictions are provided by television but only a small number of farmers in the rural areas have access to television and the local channel. Those without radios and televisions are compelled to rely on local knowledge when it comes to rainfall prediction. What emerges out of the study is the need to provide day-to-day weather prediction focusing on the local areas instead of the current national and regional weather forecasts. Moreover, means of communicating meteorological data to the rural farmers need to be identified and utilized to ensure that meteorological data is accessible to the farmers. At the end it was difficult for the study to respond to the question of the reliability and accuracy of the indigenous techniques of rainfall prediction. The need to educate farmers on the interpretation and understanding of meteorological and conventional ways of weather reporting is crucial. Farming Strategies under Prevailing Dry Conditions at Shewula The study presents strategies farmers are pursuing to cope with the dry conditions while growing in their on their plots through conservation agriculture. This is to indicate how farmers also manage the rainfall season and amount of rainfall received to grow crop on their plots. To cope with the delayed rainfall and persistent drought the farmers involved in conservation agriculture are employing the strategies in Table 2. Table 2. Strategies Practiced by Farmers involved in Conservation Agriculture to Cope with Persistent Drought. Farming Strategies Reasons for Adoption Cultivation after the first rainfall Take advantage of early rainfall in case disappears later. Delay planting time Start planting when rainfall has already started to minimize changes of crop affect by drought. Reliance on indigenous crops Indigenous crops have demonstrated reliance over drought conditions. It is also cheaper to acquire than hybrid seed. Adoption of conservation agriculture This type of farming does disturb the soil through tillage. Moreover, accumulation crop residue to protect the soil from loosing its moisture through evaporation Early Cultivation and Delay Cultivation The rainfall situation especially the delayed onset of the first rainfall at Shewula has had a significant influence on farming. As a basic coping strategy, farmers involved in conservation agriculture have altered their farming calendar. Farmers reported that those who used to start farming around August or September now start their farming on October. Those used to start farming around October have shifted to December. Those who normally cultivated their fields on November or December did not report any changes in their time of cultivation. The farmers mentioned that they changed their farming calendar to coincide with the rainfall season that seems to have moved more towards November and December instead of August as it was the case before. On the other hand farmers some farmers indicated that they resorted to cultivate early coinciding with the early rainfall which usually occurs towards the end of July or early August. However, these rains often fail to occur in recent years which result in the farmers having to wait for the start of the normal rainfall season. Cultural institutions exist that constrains the alteration of the farming calendar in rural areas. The information in Box 1 shows that farmers do not have unlimited liberty to decide when to start cultivation but the traditional authority sanctions the start and, possibly, the end of the farming season. This is a formidable constrain, especially to farmers who may want to practice early farming or farming throughout the year as it the case with conservation agriculture. Box 1 Key informant views on cultivation time Nowadays the chiefs simply command that one does not cultivate before they say so. These chiefs are young people. I now wait even if the rain has come; waiting for my chief to announce that we may start farming. The generation of today is young, so young people do things that were not done in the past years. I were to own thing with respect to cultivation using my experience as an old person, young people will quickly object and question my status in doing that. Adoption of Indigenous crops This is an era of hybrid seed especially the early maturing drought resistant cultivars. However, farmers involved in conservation agriculture have put their faith on the drought resistant indigenous crops which include sorghum (emabele labovu), white sorghum (emashali), cowpeas (tinhlumaya), indigenous maize, mung beans (mngomeni), cassava (umjumbula) and sweet potatoes (bhatata). These crops are grown solely for subsistence and exchange of seed. It is interesting to note that farmers indicated the same preference of crops should the rainfall situation improve or with the provision of irrigation. The exception is only with the options of sugar-cane, vegetables and hybrid maize. Table 3 shows preferred crops to be grown with provision of irrigation. What is different though is the motive for cultivation of the crops. To a large extent, with the provision of irrigation farmers are projecting to improving their incomes by growing the crops for sale. It must be remember that the current national challenge is to generate and improve income levels in rural areas. Introduction of irrigation may be one of the essential ingredients to bring about socio-economic development in the rural areas. The biggest problem at Shewula constraining the development of irrigation schemes is the shortage of water due to lack of flowing streams on the plateau as well as the rugged terrain. Table 3. Preferred Crops to be grown under Irrigation by Farmers Involved in Conservation Agriculture at Shewula. Name of Crop Reasons for Cultivation Cowpeas To cushion farmers in case of drought and to be grown on a large-scale for selling. Vegetables Since they demand a lot of water and they will be growth exclusively for selling. Sugar-cane Sugar-cane needs a lot of water but brings a lot of money from the sugar mills and it will be grown exclusively for selling. Maize With irrigation maize could be growth throughout the year and may be grown on a large-scale for selling. Cassava With irrigation could be grown throughout the year and for sale. Groundnuts They now can grow groundnuts which are currently difficult due to their water demand. Beans Beans need a sizeable amount of water and will be grown for sale Adoption of Conservation Agriculture Conservation agriculture was introduced at Shewula primarily to mitigate the effects of drought and promote sustainable land utilization and rural livelihoods. With its inherent minimum or no tillage, conservation agriculture allows farmers to pursue certain mechanisms aimed at retention of soil moisture and prevention of soil moisture evaporation. Farmers involved in conservation agriculture demonstrated a sound knowledge on how to improve the soil moisture retention capacity of their fields. The mechanisms in Box 2 are currently being applied by farmers to retain soil moisture and to prevent evaporation in their fields. The mechanisms include planting of cover crops, retention of residue, ripping of the topsoil, building of terraces and intercropping. The planting of cover crops and retention of crop residue is currently doubtful under the prevailing conditions. As a cultural practice, livestock are expected to roam and graze on crop residue in the winter season. The livestock do not only reduce the soil cover provide by the crop residue, they also contribute to soil compaction due to trampling as they move about grazing. Winter grazing is a formidable threat to the accumulation of crop residue which is a significant component of conservation agriculture. Conservation agriculture plots are currently fenced off to discourage livestock grazing and trampling while encouraging the growth of winter cover crops. The success of conservation agriculture in the rural areas in Swaziland, therefore, relies not only on putting up fences around the plots but also a shift in the cultural practice of winter grazing on cultivated areas. Box 2. Mechanisms applied by farmers to improve water retention on conservation agriculture plots. Planting of cover crops These are crops grown mainly to prevent the penetration of sunrays on to the soil and prevent soil moisture from escaping through evaporation. Cover crops are grown simultaneously with the main crops. The lab lab is grown only as a cover crop at Shewula not grown for consumption. However, other edible crops are grown as cover crops including cowpeas, jugo beans, and others. Retention of crop residue Residue from crops is not burnt or fed to livestock but it is allowed to accumulate on top the soil to act as cover protecting the soil from adverse weather elements and loss of soil moisture through evaporation. Cultivation of cover crops also helps in provision of crop residue to accumulate as dead material on the soil. Ripping of the topsoil Since tillage is discouraged under conservation agriculture occasionally rippers used to encourage infiltration of the little rainfall that occurs. Building of terraces Terraces are usually constructed on the fields to prevent the flow of rainwater (runoff). Terraces prevent an immediate and free flow of rain water from the fields thus encouraging water infiltration as well as preventing soil erosion. Terraces also worked as barriers for rainwater retention particularly to soils down slope. Intercropping Intercropping maximises soil cover while allowing a variety of crops with different water demands to grow in the same field. One crop acts as a soil cover to prevent loss moisture to benefit the main crop. This also cushions farmers in case one crop fails to survive dry conditions those resilient main grow to maturity and to the benefit of the farmer. It must be noted that that weather harvesting techniques are quite limited among the local farmers involved in conservation agriculture. In Zambia and Zimbabwe, farmers create basins around the crops to trap rainfall and concentrate it on the plant. This method is quite helpful in the very dry parts of country. In other countries ridges are prepared where to trap rain water and the crop is planted at the bottom of the ridge instead of the top as it is commonly done in the humid regions. A crop planted at the bottom of the ridge has direct access to the little rainfall that collects. Under moist periods the crop is usually planted at the top of the ridge. The use mulch has not been profound in Swaziland as it is the case in other countries where conservation agriculture is practiced. However, for now farmers believe that the cover provided by the residue will steadily build up overtime allow for mulch cover to be created. CONCLUSION This study was initiated to gain an insight into the indigenous rainfall prediction systems utilized by the farmers involved in conservation agriculture as well as the strategies they have adopted to cope with the persistent drought. The study also sought to identify ways of improving the moisture retention capacity of the soil in their conservation agriculture plots. The various methods of rainfall prediction presented above indicate that farmers rely on natural phenomena such as winds, vegetation, animals, rocks and others to predict rainfall incidence. The study has also indicated that farmers seem to attach more trust and confidence on their own systems of rainfall prediction than the conventional ones. It is difficult for the farmers to relate to conventional systems because of problems of accessibility to the media disseminating weather prediction reports. It is emerging clearly that access to such media by the farmers is crucial and needs to be improved. Moreover, indigenous knowledge systems for rainfall prediction need to be incorporated into the conventional ones and be brought to the consumption of the farmers. This may alleviate uncertainty among farmers as far as information about rainfall prediction and occurrence is concerned. The study has presented strategies farmers have adopted to cope with the persistent drought. The study established that the farmers delay cultivation until late in the year to coincide with the often delayed rainfall. The rainfall situation was, therefore, found to have had an influence in the change in times of commencement of the farming season. Farming which used to start at around August and September of every year has been shifted to November or December. An interesting situation revealed by the study is the manner in which farmers have reverted back to the cultivation of indigenous crops especially in the era of abundant drought resistant hybrid seed. Though it was difficult to ascertain the basis of such a development but it was established that the farmers were adamant that indigenous crops were more tolerant to drought that some of the hybrid seed. Farmers were also found to be concerned about improving the moisture retention capacity of their soil. This was mainly facilitated by the adoption of conservation agriculture which had inherent mechanisms such the retention of crop residue to accumulate as soil cover, intercropping, building of terraces and others which are crucial in the improvement of moisture retention capacity of the soil. It could be concluded that conservation agriculture may presents the Shewula community with a sustainable way of producing their food crops without any adverse effects on the harvest and soil in the prevailing dry conditions. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This is to acknowledge the contribution of the farmers at Shewula involved in conservation agriculture as well as the two elderly gentlemen who agreed to be key informants of for the study. They are listed below: 1. Make Tfumbatsa 2. Make Dladla 3. Make Dladla 4. Make Mhlanga 5. Babe Masimula 6. Mkhulu Mnisi 7. Mkhulu Mahlalela 8. Babe Mnisi 9. Babe Mahlalela 10. Ndumiso Masimula REFERENCE COSPE/FAO/Government of Swaziland (2005). Conservation Agriculture as a Sustainable Approach towards Food Security for Rural Communities in Swaziland. A report presented in an FAO Meeting on Conservation Agriculture at Mpophoma in Swaziland in May, 2005. Desrpsch, R. (1998). Historical review of No-tillage Cultivation Crops. Proceedings, First JIRCAS Seminar on Soybeans Research. March 5 – 6, 1998. FOZ Iguacu, Brazil, JIRCAS Working Report No. 13, pp. 1 – 18. Ellis, F. 2000. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity Countries. Oxford: University Press. ETC-Foundation. 1987. Wood Energy Development: Policy issues. A report prepared for the SADC Energy Sector. Fakudze, P.N. 1998. Report of the Survey of Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Swaziland and the Potential for its Integration to the National Action Plan for Combating Desertification. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives: Mbabane. Fakudze, P.N. Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Swaziland: A benefit or a threat to biodiversity. A paper presented at the workshop on local knowledge, gender and biodiversity held at UNISWA, Luyengo campus on March 16, 2001. Kasenene, P. 1993. Swazi Traditional Religion and Society. Websters: Mbabane. LORE. 1992. Capturing Indigenous Environmental Knowledge. International Development Research Centre: Ottawa. Manyatsi, A.M. 2001. A Review if Indigenous Knowledge and Technology for Community-based Resource Management in Swaziland. Paper presented at workshop on FAO workshop on Institutions Working on Gender, Biodiversity and Local Knowledge. University of Swaziland, Luyengo, Swaziland. 16-17 March, 2001 Matowanyika, J.Z.Z. 1999. Hearing the Crab’s Cough: Perspectives and emerging institutions for indigenous knowledge systems in land resources management in southern Africa. IUCN ROSA: Harare. Mavimbela, H.C. 2004. Biodiversity Management: Indigenous knowledge on traditional food plants among Rural women. Unpublished MSc. Thesis: University of Swaziland. Mlipha, M. 2004. ‘Crop Production Through Conservation Farming: A case study of conservation agriculture at Shewula, Swaziland’, in Cheryl le Roux (ed.). Our Environment. Our Stories. Pretoria: University of South Africa. Moser, C.O.N. 1996. Confronting Crisis: A comparative Study of Household Responses to Poverty and Vulnerability in Four Poor Urban Communities. Washington D.C.: World Bank. Osunade, M.A.A. 1994. ‘Community Environmental Knowledge and Land resource Survey in Swaziland’ in Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography v.15. pp. 157 – 170. The World Conservation Union (IUCN). 1995. Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Natural Resource Management in Southern Africa: Case studies from Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe, compiled by Vielka Garibaldi. IKS Series No. 3. IUCN (place not stated). Warren, M.D. & Slikkerveer, L.J. 1995. The Cultural Dimension of Development. Intermediate Technology Publication: London. Woodhouse, P. 1998. ‘People as Informants’, in A. Thomas, J. Chataway & M. Wuyts (eds.), Finding out Fast: Investigative Skills for Policy and Development. London: Sage, pp. 127-140.