The Politics of Creative Writing in the Academy

advertisement

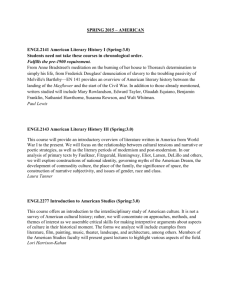

Ron Strickland The Politics of CreativeWriting in the Academy The number of creative writing programs in colleges and universities has been growing steadily over the past quarter century. In 1975 there were only 21 graduate degree-conferring programs in creative writing; by 1996 the number had grown to 238. (There were 27 undergraduate degree-conferring programs in 1975, compared to 310 in 1996). (Source: "A Brief History of the AWP," http://www.gmu.edu/departments/ awp/history.html [accessed June 8, 1999]. In this paper I want to look at what this growth indicates about the political and economic configurations of English departments. There is little question that creative writing programs have been a reactionary force during the past fifteen years or so--that is, since the onset of the conservative backlash against the "theory revolution." Some observers would suggest that there was a period from 1970 to 1985 or so in which the net effect of creative writing programs was to democratize English departments and to provide a space for opposition to the traditional cultural hegemony in departments. I want to look at this history briefly, in order to determine whether and how we might occupy the curricular and institutional space of creative writing as a space for revolutionary opposition. The question is, is there any redeeming radical potential in these programs, or are they merely safe havens for antiintellectualism and neo-romantic individualism? First, there's the question of where to begin. Perhaps 1967, when the Association of Writing Programs (AWP) was founded. There were a few writing programs--notably the Iowa Writers' Workshop--going back to the forties and fifties, but, as the table in my 02/12/16--Strickland/2 handout shows, the numbers really began to grow in the seventies. I would connect this growth to the growth and transformation of the American university system resulting from Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society" pledge to make a college education available for every high school graduate who wanted one, and, of course, to Johnson's war for making every draft-eligible high school graduate want one. Like many other curricular innovations of that period--the growth of courses in contemporary, American and popular literature, the establishments of Black studies programs, etc.--creative writing could be seen as a democratizing force. Students didn't have to know the literary canon very well to succeed in creative writing courses, and they usually didn't have to know the rules of grammar or rhetorical conventions either. So, under-prepared working-class and minority students who might be at a competitive disadvantage in traditional literature courses could find a haven in creative writing courses. I think many of them did, though I don't have statistical data for this perception. I would, however, point to the fact that many of the first wave of African-American professors in predominantly white universities--and practically all of the first generation of minority "star" academics--were creative writers. So, I'm ready to believe that, in institutional and demographic terms, creative writing was at least potentially a progressive, revolutionary presence in English departments. Curt White seems inclined to think that this revolutionary potential was there in intellectual terms as well. I'm less inclined to believe that, but it's something we can argue about in more detail later. What is pretty clear is that conservative literary scholars saw creative writing programs as dangerously vulgar and democratic. Curt has been fighting with conservatives in the AWP about this for years. And other observers, 02/12/16--Strickland/3 have addressed it as well. One good liberal critique is that of Eve Shelnutt in a 1992 essay entitled "Notes from a Cell: Creative Programs in Isolation" (Joseph Moxley, ed., Creative Writing in America: Theory and Pedagogy, NCTE, 1992). Like Curt, Shelnutt is concerned to argue that creative writers need to read theory. But by the early 1990's, creative writing faculty had formed a coalition with traditional humanist literary scholars-those same scholars who had opposed the creative writers most strongly during the 1970's--in alliance against the theory revolution. This intellectual rapprochement against theory put traditional literary scholars in an embarassingly compromised position from which they never recovered. For years they had been dismissing creative writing as lacking academic rigor and standards. Apparently, they were right about this. But suddenly, faced with the revolutionary intellectual threat of postmodern theory--which was much more intellectually rigorous than the vast bulk of traditional humanist literary scholarship--the humanist literary establishment embraced the rabble and threw in with their former enemies. As Donald Morton and Mas'ud Zavarzadeh have demonstrated, the intellectual/political basis for this unholy alliance is more political than intellectual. In an essay entitled "The Cultural Politics of the Fiction Workshop," Morton and Zavarzadeh construct this alliance as a relatively direct expression of the interests of the dominant capitalist order: In its efforts to keep intact the legitimacy of bourgeois values embodied in such undertakings as the "professionalization" of social practices, the ideological arm of the dominant economic regime in the academy has engaged in a new mode of institutional politics, the purpose of which is to build up a new coalition of all 02/12/16--Strickland/4 those academic "experts" and "professionals" who acquire their own cultural hegemony from the ruling social order. It is part of this coalitionism that in English departments all across the United States at the present moment a political rapprochement is being negotiated between traditional humanist scholar-critics and creative writers. It is historically significant that humanist scholars, who are now seeking a political alliance with creative writers, are the very people who a decade or so ago were opposed to establishing creative writing programs in their departments. Creative writing programs, the traditionalists used to argue, were intellectually "soft," and their existence in any department would inevitably lead to a "lowering of academic standards," since they enabgled students to obtain degrees in English without haveing been subjected to the rigors of historical scholarship and other critical training. Under the pressure of radical critical theory, that argument has now lost its ideological usefulness, and instead, in a new political move, humanist scholars and critics are embracing creative writing programs as bastions of the inviolable human imagination. . . . (159-60) I'll summarize Morton and Zavarzadeh's specific theoretical critique: First, they argue, The dominant fiction workshop . . . adheres to a theory of reading/writing to be not so much "produced" by cultural and historical factors as by the intervention of the author as reflected in the "text itself." According to this humanist notion of meaning, a text (like language) acquires its meaning because of the reality which is located outside it and to which it faithfully "represents" and "refers." The 02/12/16--Strickland/5 author is the "authority" who situates the text aesthetically in relation to "reality," and his verbal skills and craftsmanship in making the text "correspond" with reality are, in the last analysis, acts of a sovereign imagination--unaccountable and unanalyzable moments of intuition, originality, and inventiveness. (157) These assumptions are opposed to postmodern critical theory, which In all its various forms argues that acts of reading/writing the texts of culture, which shape the "meaning" of (cultural) reality, are not a matter of the reader/writer's "private taste," "intuition," sensitivity," "vision," or "originality." They are, in other words, not "natural" acts, but complex social practices which are acquired by the people of a culture in the process of being socialized through education--in the inclusive sense of the word, in schools, churches, families, sports, and so on. (156) Futher, they argue, the fiction workshop functions largely to preserve a neoromantic individualist subjects: The fiction workshop is not a "neutral" place where insights are developed, ideas/advise freely exchanged, and skills honed. It is a site of ideology: a place in which a particular view of reading/writing texts is put forth and through this view support is given to the dominant social order. By regarding writing as "craft" and proposing realism as the mode of writing, the fiction workshop in collaboration with humanist critics fulfills its ideological role in the dominant academy by preserving the subject as "independent" and "free." (161) 02/12/16--Strickland/6 Finally, the workshop most forcefully squashes the very individuality that it ostensibly nurtures: The visible and external mark of the unique "voice" of the singular writer is his or her "style." The cultural paradox of the fiction workshop--a manifestation of its ideological contradictions--is that while the workshop focuses on style, which is the materiality of writing, it in fact is bent on eliminating it. . . . The style of the writer is to be so translucent as to be translucent as to be non-existent. Style, in other words, establishes the uniqueness of the individual, but its transparency immediately enables the individual to trasncend "writing" and "difference" (materiality) and reach a transdiscursive space in which the writer can in his absolute imaginative freedom communicate with equally unfettered readers. Morton and Zavarzadeh wind this passage up by quoting Tess Gallagher: "I want my fiction to be transparent. I want it to involve the character and experiences, but I don't want the language to be visible (166)." And they end the essay with an analysis of the ways that experimental and innovative fiction are excluded from the creative writing workshop and the conservative effects of the workshop's predilection for "realism." They propose that the only way to rescue the creative writing workshop would be to subject it to an ongoing critique: It is only through a sustained theoretical interrogation of its practices that the workshop can be reconstituted as a site for the radical reading/writing of texts of culture and through such transgressive activities intervene in the domiant relations of production and in the existing exploitative social arrangements. The "voice" of 02/12/16--Strickland/7 the free-standing individual writer trained in the fiction workshop is the "voice" of the entrepreneur, and as such it is a device employed to perpetuate political and economic oppression in the guise of "freedom." Instead of "resisting" theory in the name of the free subject, the fiction workshop should be the pedagogical space in which the processes of signification in texts of culture are to be examined and the construction of what is represented as "reality" is made intelligible. (175) This critique is largely compatible with Curt's critique of the current state of literary publishing, though Morton and Zavarzadeh don't elaborate the connection between mainstream publishers and the media and academic creative writing programs as Curt does. I find the critique persuasive, and I expect that most of you will, though the brief call for transformation at the end is comically utopic. I want to turn, though, at the end of this paper, to the question of whether and how it might be possible to rescue creative writing in the academy for some such sort of revolutionary ends. I think Curt has been trying to do this in our program, for years, by trying to recruit very smart students who will read theory, who will not hide from theory behind the screen of neo-romantic individualism. I don't think this has worked, even in our program, much less in the many departments where the creative writing faculty have no interest in questioning neo-romantic individualism. One reason it won't work without some kind of drastic change in the workshop format is that, even if a teacher wanted to change this pattern, most students would resist. I see this in our program all the time. We have innovative fiction writers like Curt White and David Foster Wallace, and we get students showing up who want to learn to write like Hemingway and Fitzgerald. These 02/12/16--Strickland/8 students are a conservative bedrock. And departments are going to be depending more and more on them. One of the ways that the academy will respond to the academic job crisis is to expand the creative writing programs even further. Unlike literature and rhetoric graduate students, who usually have some hope of finding an academic job after completing their degrees, creative writing students often have no illusions about academic employment. For many creative writing students, graduate school is like a twoyear discount vacation in Bohemia. They get to go hang out in the ambiance an academic ghetto for a couple of years, meet some famous writers, etc. They may end up with a few more thousand dollars in student loans in the end, but it's no more expensive than bumming around Europe for a year. What could we do to radicalize these slackers? I don't know. One thing I'd be willing to try would be to open up the workshop, to break down the wall between creative writing and literary theory by maybe requiring all literature students to take creative writing workshops, the way some programs (ours included) require creative writing students to take literature and theory courses. Maybe some sort of "theorized" workshop could be designed, something that would be teamtaught by a literature teacher and a creative writer. I'd be willing to try my hand at it. 02/12/16--Strickland/9 Works Cited: Morton, Donald, and Mas'ud Zavarzadeh. The Cultural Politics of the Fiction Workshop." Cultural Critique, Winter 1988, 155-173. Parini, Jay. "The Limited Value of Master's Programs in Creative Writing." Chronicle of Higher Education, November 23, 1994, A56. Shelnutt, Eve. "Notes from a Cell: Creative Writing Programs in Isolation." In Joseph Moxley, ed., Creative Writing in America: Theory and Pedagogy. Urbana: NCTE, 1992, 3-24. White, Curtis. Monstrous Possibilities: An Invitation to Literary Politics. Normal: Dalkey Archive Press, 1998.