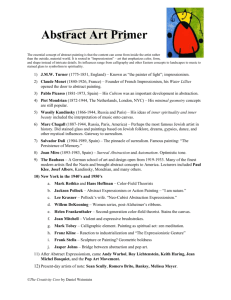

Abstract Art: A Universal Language

advertisement