Stevens-Johnson/TEN

advertisement

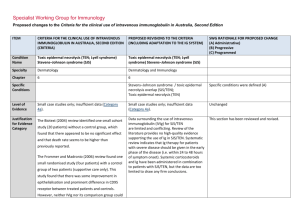

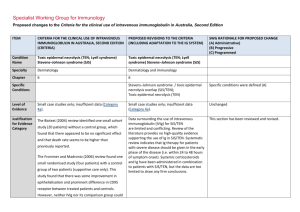

STEVENS-JOHNSON SYNDROME Allen Repp, M.D. December 4, 2002 Introduction In 1922, Stevens and Johnson first described a syndrome of fever, stomatitis, ocular involvement, and a diffuse macular rash in children SJS now refers to a vesiculobullous disease of mucosal surfaces and skin in children and adults Due to overlap of clinical features including lesions of skin and mucous membranes and associations with drug exposure or infections, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have traditionally been considered severe manifestations of erythema multiforme (EM) – and the term erythema multiforme major has been used as a synonym to SJS by some However, more recent literature has suggested that SJS and TEN are distinct from EM based on some clinical and histopathologic characteristics The spectrum of erythema multiforme is characterized by typical target lesions in a postinfectious period with relatively low morbidity (although the condition may be recurrent) The spectrum of SJS/TEN is characterized by more diffuse blisters and purpuric macules, is more commonly associated with exposure to drugs, and has a high morbidity In this concept, SJS and TEN represent gradations of severity of the same type of response Classification Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Mucosal erosions and epidermal detachment <10% body surface area Overlap SJS/TEN Epidermal detachment 10-30% body surface area Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Epidermal detachment > 30% body surface area Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis without Spots Epidermal detachment > 10% body surface area with large epidermal sheets but without macules or target lesions Clinical Presentation of SJS/TEN Children and young adults most commonly affected In SJS attributed to drugs, offending agent usually initiated approximately 1-3 weeks prior to onset of mucocutaneous eruption Prodromal illness with symptoms of fever and upper respiratory infection often precedes mucocutaneous eruption by 1-14 days Mucosal lesions: Involvement of at least 2 mucosal membranes is a major clinical feature of SJS and TEN Patients often present with dysphagia, odynophagia, photophobia, and/or dysuria Bullous lesions on conjunctivae, mucous membranes of mouth, nares, anorectal junction, vulvovaginal region, urethral meatus, and esophagus Ulcerative stomatitis with hemorrhagic crusting is classic feature Cutaneous lesions: Description: Initially, flat atypical targets or purpuric maculae that may be described as painful or burning. Lesions coalesce to form blisters that may then progress to epidermal detachment. Location: Symmetric, on upper trunk, or widespread. Reportedly, the lesions never involve the hairy portion of the scalp. Other findings: Confluent erythema, facial edema, central face involvement, tongue swelling, palpable purpura, skin necrosis, epidermal detachment with lateral pressure (Nikolsky’s sign), mucous membrane erosions may all be seen, and all portend more serious condition Ophthalmologic manifestations: Conjunctival lesions occur in 85% of patients Ophthalmologic involvement may range from mild conjunctival hyperemia to pseudomembrane formation to keratitis to corneal ulcerations. Synechiae may develop between conjunctiva and eyelids. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Residents’ Report Long-term complications can include photophobia, corneal scarring, disruption of tear film, visual impairment, trichiasis (in-turned eyelashes), and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (chronic, scarring inflammation of ocular mucosa). Pulmonary manifestations: Patients may present with dyspnea, harsh cough, bronchial hypersecretion, hypoxemia, and/or patchy interstitial infiltrates on radiography, representing involvement of bronchial epithelium. Laboratory findings: Anemia and lymphopenia are common, with neutropenia present in up to 1/3 of patients Elevated transaminases (2-3x normal) found in up to ½ of patients Complications: infection, hypovolemia and hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, malnutrition Etiologies Drugs Most cases of SJS are attributed to drugs, with a strong association to a specific medication identified in approximately 80% of cases. Patients undergoing treatment for seizure disorders are most frequently affected Most commonly implicated drugs: sulfonamides (RR 172), carbamazepine (RR 90), oxicam NSAIDs (RR 72), corticosteroids (RR 54), phenytoin (RR 53), allopurinol (RR 52), phenobarbitol (RR 45), valproic acid (RR 25), cephalosporins (RR 14), quinolones (RR 10), aminopenicillins (RR 7) Infections Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, herpes simplex virus infection, and upper respiratory tract infections have all been implicated in SJS (although more clearly associated with erythema multiforme) Predisposing Illness HLA B12, HIV, and SLE have been associated with higher incidences of SJS Pathophysiology Pathophysiologic mechanisms not well elaborated. Current popular theory proffers that reactive drug metabolites may bind to carrier proteins on the membranes of epidermal cells and act as haptens, inducing primarily lymphocytic reaction, inflammatory cytokine release, cell death, and tissue necrosis. Diagnosis Primarily clinical diagnosis Biopsy of denuded epidermis may be helpful if classic lesions not present demonstrates perivascular mononuclear infiltrate in papillary dermis, subepidermal blister formation, and full thickness epidermal necrosis Differential diagnosis includes dermal-epidermal vesiculobullous diseases (erythema multiforme, bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, porphyrea cutanea tarda, and paraneoplastic pemphigus), exfoliative erythroderma, staph scalded skin syndrome, acute exanthematous pustulosis Treatment Early recognition and withdrawal of potential causative agents Supportive care (similar to burn patients): aggressive fluid repletion, strict hygiene precautions, surgical debridement and/or whirlpool therapy to remove necrotic epidermis, artificial tears, regular ophthalmologic exams Treatment of secondary infections Directed therapy: Corticosteroids controversial (mixed data). IVIG somewhat effective in small retrospective trial. Cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, plasmapheresis, and GCSF have all been tried, but lack supporting data. Some authors advocate empiric use of acyclovir regardless of demonstration of HSV. Prophylactic therapy: for cases of recurrent erythema multiforme associated with HSV, there is some evidence supporting chronic oral acyclovir use. Prognosis SJS associated with < 5% mortality, whereas TEN associated with up to 44% mortality. Sepsis is major cause of death. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Residents’ Report