Collection Evaluation - Xavier University Libraries

advertisement

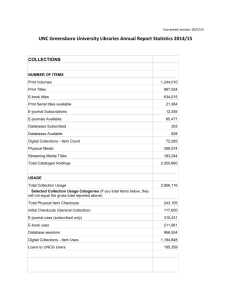

COLLECTION EVALUATION Collection evaluation is a continuing, formal process for systematically analyzing and describing the condition of a library’s collection and to indicate areas needing improvement. Evaluations are conducted to provide several kinds of important information to libraries. They help clarify the library’s goals in the context of its mission and budget, supply data used to set funding priorities, and build a base for long-range planning and administration. But why is collection assessment conducted? (Collection evaluation and collection assessment will be used interchangeably in this paper.) This paper will answer this question by presenting the benefits of evaluation, the various evaluation techniques with their strengths and shortcomings. Benefits of Conducting Collection Evaluation Collection evaluation provides library administrators with a management tool for adapting the collection, an internal analysis tool for planning, a tool to respond systematically to budget changes, and a communication tool and data for resource sharing with other libraries. Library staff can also benefit by having a better understanding of the collection, a basis for more selection collection development, improved communication with similar libraries, and enhanced professional skills in collection development. For libraries involved in resource sharing, collection evaluation is essential in determining how each library fits into the system and what should be expected for each library’s further growth in the context of the cooperative relationship. It goes without saying that before any meaningful evaluation of the library’s collection can take place, the goals and purposes of the collection should be stated in a collection development policy. Since the development of a collection can be very subjective, a written policy about what is to be selected or rejected becomes essential to evaluation. The Importance of Planning When planning a collection evaluation, it is important to carefully define the goals for the program, choose the most appropriate method(s) to be used, and establish what information is needed. An evaluation can be fully comprehensive or it can focus on specific areas, depending on the library’s needs (and the resources available to carry it out – evaluations can be expensive!). It can be very tempting to gather all sorts of information because it seems interesting, but it may be useless if it does not fit into the parameters of the evaluation. Be sure that everyone participating in the evaluation understands what is expected and when tasks should be completed. Evaluation Techniques There are a number of standard techniques for obtaining evaluation, but they can all be considered as either collection-centered or client-centered. Collection-centered techniques examine the content and characteristics of the collection to determine the size, scope, and/or depth of a collection, often in comparison to an external standard. Client-centered techniques measure how the collection is used by library users. A. COLLECTION-CENTERED TECHNIQUES Collection-centered techniques are employed to examine an existing collection and to compare its size, scope, depth, and significance with external criteria. The methods include: 1. list-checking 2. shelf scanning 3. compiling statistics 4. application of standards 5. formula method 6. conspectus evaluation List-Checking This method compares the collection to authoritative lists of what is available and appropriate for a particular type of collection. There are hundreds of possible lists to use and It is important to carefully interpret Presumably, a high percentage of titles found indicates an excellent collection, although at this time there is no agreed upon interpretations or weightings of percentages held. The type of list selected depends on the type of collection being evaluated and the purposes of the evaluation. For example, a “basic” collection serving an undergraduate program may be checked against “standard” lists developed for this type of collection. It is crucial that the list match as closely as possible the libraries’ objectives. Types of lists include: standard catalogs and basic general lists such as Books for College Libraries and Choice’s Opening Day Collection printed catalogs of the holdings of important and specialized libraries specialized bibliographies and core lists current lists such as acquisition lists of major libraries, books of selected publishers, or annual subject compilation lists of types of materials, such as reference works, periodicals, etc authorized lists prepared by governmental authorities or professional associations lists, usually in current journals or review sources of evaluated publications at the forefront of current research Procedures Decide on lists appropriate to the subject and goals of the library; Decide whether to check the lists completely or by sampling; Assign staff responsibility and check lists against card catalog or online public access catalog; Record the number of titles held that are listed in the bibliography being checked; Determine percentage of library holdings in relation to number of titles on each list; Analyze results and integrate findings with results of other techniques to determine the collection level. The advantages of list-checking include: a wide variety of published lists is available; many lists are backed by the authority and competence of expert librarians or subject specialists; provides concrete, objective picture of holdings; may be carried out by support staff/procedure of searching lists is easy; provides specific items that may be purchased to strengthen collection; quantitative results useful for budget justification, accreditation studies, etc. The disadvantages of this technique include: many lists are not revised and become out-of-date; lists representing the viewpoint of one individual or group may not represent the subject well; lists may not be as representative of the library’s subjects or purposes or the interest of its users; may be difficult to evaluate their validity, usefulness, relevance, etc. in some subject areas, lists may be hard to locate or compile. It is important to carefully interpret the qualitative data that result from checking lists, considering who assembled the list and for what purpose. List checking can help the library staff understand the size and scope of possible materials, and it can be helpful in assessing what should be added to the collection. Because there are many possible lists to check and they are quickly outdated, this can a time- and labor-intensive method, especially if you do not have an automated system. Misleading results can occur when the same “best book” lists are used for selection as 2 well as evaluation, when published lists are written for a very different audience than the library’s community, and when lists don’t include works owned by the library that are as good or better for the local community than the materials on the list. Shelf Scanning This technique involves examining the collection directly. With this procedure, a person physically examines materials on the shelf; the person then draws conclusions about the collection’s size, scope, depth, and significance; its recency; and its condition. Preservation, conservation, restoration, or replacement of materials may be taken into consideration in this process. Examination of date due slips provides samples of actual use. Procedures 1. Select classification area. Work with someone if possible. 2. Gather necessary tools. 3. Determine scope: examine every item or a sample. 4. Determine location of other materials in the collection that need be considered: electronic documents, periodicals, vertical files, commercial databases, reference tools, etc. 5. Look for such things as: physical condition of the materials (weeding needed?) types of materials language serial runs: complete? Broken? Bound? With our without deficiencies? scope, extent of the collection special problems multiple copies 6. Record findings. The advantages of using this technique include: providing immediate, relevant results can be done quickly provides overall view of the size, scope and quality of the collection builds on knowledge and expertise of the evaluator evaluator sees what the users see can be used to accomplish goals other than evaluation The disadvantages of this technique are: subjectiveness and impressionistic, does not produce quantitative or comparable results persons knowledgeable in a subject area and its literature are required and such individuals may be difficult to locate, unable to invest time, or charge fees greater than the library can afford results may be biased if conducted by the librarian who developed the collection or currently selects for it some materials may not be on the shelf This technique is well-suited to smaller libraries and areas of a collection that don’t fit into the classification scheme. It has the advantage of providing relevant information quickly, but it can be highly subjective, especially if the person doing the evaluation also does the selection. Working in a team should be encouraged. Direct examination should not be used as the sole evaluation technique. Shelf-scanning should be conducted after the shelflist data have been collected; the two techniques complement each other to provide a reliable characterization of the collection. Be sure to examine the entire collection, including periodicals, audiovisuals, and reference works. You should make notes on items that should be weeded, but do not weed as you assess. Depending on the size and type of you r collection, you may not need to examine every item; sometimes a sample works just as well. Compiling Statistics Traditionally, the main comparative methods for evaluation of collection strengths were aggregate figures on collection size and material expenditures. This information is typically reported in annual reports. The following statistics are typically collected and reported by libraries: Size: this may be the measure of titles, volumes, or portions of the shelflist in specific call number ranges Net volumes, titles, or units added: this measures growth rates in total collection size, specific portions of the collection, or in various formats, for example, books, microforms, or periodicals Expenditures for library material: this may include money spent for all material or for specific formats or portions of the collection. Figures may be annual and may be expressed in pesos or a proportion of the total or institution budget The advantages of collecting statistics include: some statistics may be easily maintained, for example, shelflist counts performed every 4-5 years if proper records have been kept, they are easily available if clearly defined, they may be widely understood and comparable automated library systems should be able to extract this easily and perform some preliminary analysis The disadvantages of this technique include: statistics may be recorded improperly clear definitions of units may be lacking statistical records may not be comparable significance of statistics may be difficult to interpret Application of Standards This technique analyzes government standards or an accrediting group’s standards. Such standards vary a great deal in format and specificity. The advantages of using this technique include: for the appropriate type of library, the standard will generally relate closely to the library goals standards are generally widely accepted and authoritative they may be promulgated and used for evaluation by accrediting agencies, funding agencies, and others; they may be very persuasive in generating support for the library. The disadvantages of applying standards include: some are stated generally and are difficult to apply they may require a high degree of professional knowledge and judgment knowledgeable people may disagree in application or results minimum standards may be regarded as maximum standards Formula Method Various formulas have been conducted to assess the quality of library collections. Among the formulas that have received wide attention include: Clapp-Jordan, the ACRL formula for college libraries, the ACRL formula for college libraries. Mention can also be made of the formula presented during PAARL’s seminar Procedures depending upon the formula used. Advantages associated with formulas include: greater potential for in-depth comparison between libraries greater ease in preparation and interpretation The disadvantages of this technique are: 3 in ability to assess qualitative factors that are important in the relationship between the library collection and patron needs lack of standard definitions of what to measure, e.g., there is no uniformity in use of the terms titles and volumes. Evaluation by Outside Expert A knowledgeable person from outside the library staff can be enlisted to survey a portion of the collection and provide qualitative data. Outside experts include consultants, other librarians, a faculty member, or a library user with specialized knowledge, surveys a portion of the collection. If you choose to use an outside expert, be sure that the expert understands your assessment goals and that you are asking for advice which may or may not be implemented. That person’s contributions should always be recognized. The advantages of this method include: brings a fresh perspective to the collection facilitates mutually advantageous communication between librarians and administrators, staff and users The disadvantages of this technique include: evaluation may be impaired by bias, narrow or specialized view, or lack of understanding of the library’s collection policy subjectivity of the evaluator may be difficult to find an outside expert, or expert may not be available when needed Conspectus Evaluation The term “conspectus” was developed by the Research Libraries Group in the United States to refer to a standardized means of evaluating library collections in each of the subjects, categories, and divisions. Developed in the 1970’s and 1980’s, it was originally intended for large academic libraries, but it has been adopted and used by other types and sizes of libraries, as well. The conspectus method provides a framework to describe their collection strengths and current collection intensities. The evaluation levels indicate the appropriateness of the collection to support certain subjects at certain levels, so they have immediate relevance for collection development, for example, if you have a level 3 collection but the academics are running strong research programs, you’d better improve that area of the collection. Conspectus uses a Collecting Level Indicator (0 to 5), or summary, of a library’s Current collecting Level (CL); Acquisition Commitment (AC) and Collecting Goal (GL). Libraries can also supply additional information about strong collections, notable items in the collection, number and median age of items held, and the selection policy for a particular part of the collection. N.B. Refer to previous notes on the collection code levels The advantages of conspectus evaluation include: the detailed subject breakdown of the conspectus allows for more finely delineated collection descriptions collections and collecting patterns are described in comparable terms conspectus values are easily accessible online or in paper format cooperative collecting or preservation policies can be developed using the conspectus as an instrument to map collection strengths The disadvantages of this technique include: this method is labor-intensive it is based to a considerable extent on subjective judgments, although supplementary guidelines reduce the level of subjectivity the approximately 6,000 subject descriptors may be too detailed for some libraries or portions of their collections. Reducing the number of descriptors for local purposes requires additional work and must maintain alignment with the full set for comparability the subject descriptors B. USE-CENTERED TECHNIQUES While collection-based techniques focus on whether or not the libraries have obtained the materials they intended to, use-centered techniques go beyond the collection itself to determine how the collection is used by library users and to answer to questions like: can library users identify and locate the items they need, are the specific items indeed available, what unmet needs exist, and who the users are. Analysis of the results of such studies may provide information for other subsequent collection development activities, such as planning, budgeting, or weeding. The methods include: 1. circulation studies 2. in-house use studies 3. survey of user opinions 4. shelf availability studies 5. simulated use studies 5.1 citation studies 5.2 document delivery tests Circulation Studies Studying collection use patterns as a means of evaluating collections has been quite popular. Two basic assumptions underlie use/use studies: a) the adequacy of the collection is directly related to its use by students and faculty, and b) circulation records provide a reasonably representative picture of collection use. These studies analyze circulation data to determine trends in use of part or the total collection, by user group, by purchase date of book, or by subject area. Data of these types can be used to: identify little-used portions of the collections that can be retired to less accessible and less expensive storage areas identify a “core” collection of items likely to satisfy some specified percentage (say 90%) of all circulation demands within the near future. These titles which are heavily used may therefore require duplication, or treatment in some other way, to improve their availability identify use patterns of selected subject areas or types of materials by comparing their representation in the total collection (expressed as a proportion of titles or volumes available) to their circulation (expressed as percentages of all circulations). The resulting information is helpful in adjusting collection development practices or fund allocations. Identify user populations and/or relative use by different populations Such data are usually gathered more easily from an automated circulation system, but some of them have not been designed to provide data in the format desired for a given study. The advantages of circulation studies include: data are easily arranged into categories for analysis allows great flexibility as to duration of study and sample size units of information are easily counter information is objective with today’s circulation systems, use data becomes increasingly easy and inexpensive to gather The disadvantage of these studies include: 4 excludes in-house consultation and thus under-represents actual use reflects only successes and does not record user or collection failures may be biased through inaccessibility of heavily-used material fails to identify low use due to obsolescence or low quality of collection circulation data cannot reflect the use generated within the library such as reference collections and noncirculating journals circulation data cannot reflect the use generated within the library even for circulating items, there is no way of knowing how the material was used; perhaps the volume was used to prop open a window or press flowers value derived from a circulated item is unknown, making it difficult to accurately assess the collection’s worth In-House Use Studies Several techniques are available for recording the use of materials consulted in the library and re-shelved by library staff. This type of study can be approached from two directions: materials used and users of materials. The study can focus on the entire collection or a part of the collection and/or on all users or a sample of users. The definition of use must be clearly specified, i.e., at table, at shelf, etc. While some in-house use may appear casual or of minimal importance, such as at-the-shelf-use, there is a potential danger of assigning values to different types of uses. The extent to which patterns of in-library use parallel patterns of at-home use remains controversial and little has been published about the values to patrons of different kinds of reading or consulting of library materials Use data, normally circulation figures, are objective and the legitimate differences in the objectives of the institution that the library serves do not affect the data. One can tailor use studies to fit the library, rather than forcing the library into a standard mold. They are also helpful in deselection projects. An important factor is to have adequate amounts of data on whc8ih to base a judgment. With today’s computer-based circulation systems, use data becomes increasingly easy and inexpensive to gather. The advantages of these studies include: user approach to in-house use gives a more complete picture of in-library use than a study which focuses on materials. It can be used to correlate type of user with type of materials used can be used in conjunction with circulation study focused on same part of the collection to give more accurate information on use of the collection regular pattern of sampling periodical use combines in-house and out-of-library use can tailor use studies to fit the library, rather than forcing the library into a standard mold helpful in deselection projects The disadvantages of in-house use studies include: difficult to use in uncontrolled or open stack areas because of the need to rely on users’ cooperation. Probably have to supplement by direct observation to ascertain appropriate correction factor for noncooperating users timing of the study during the year, such as during a peak period or slack period, may bias results materials “in circulation” are not available for in-house use and this may bias the observations reflects only successes; does not indicate user or collection failures Survey of User Opinions The goal of a user survey is to determine how well the library’s collections meet the user’s information needs by gathering written or oral responses to specific questions. Information from user surveys can be used to: evaluate quantitatively and qualitatively the effectiveness of the collections in meeting users’ needs provide information to help solve specific problems define the makeup of the actual community of library users identify user groups that need to be better served provide feedback on successes as well as deficiencies improve public relations and assist in the education of the user community identify changing trends and interests The advantages of user surveys include: it is not limited to existing data, such as circulation statistics permits direct feedback from users can be as simple or complex as desired The disadvantages of this method include: designing a sophisticated survey is difficult, i.e., it is difficult to frame unambiguous questions that will yield quantifiable results analyzing and interpreting data from an opinion survey to get usable information is difficult and imprecise most users are likely to be passive about collections and so must be approached individually and polled one at a time, increasing the costs of conducting the survey some users may not cooperate in the survey and thus results may be skewed many users are not aware of what their library should reasonably be expected to do for them and therefore have difficulty in judging what is adequate user surveys may record perceptions, intentions, and recollections which do not always reflect actual experiences users interest may be focused more narrowly than collection development policies. This may introduce a negative bias in the survey results. By definition, surveys of user opinions will miss valuable statements from and about the nonuser Shelf Availability Studies This approach is used to determine whether or not an item presumed to be in the collection is actually available to the user. While other methodologies depend on simulation, this technique monitors user inquiries directly and measures how often the collection is deficient when a user cannot find an item and how often the user’s error causes an item to be inaccessible. During a specified period, users are asked to name the titles that they failed to find in the library. One method is to interview users, another to administer questionnaires as users leave the library or to provide “failure slips” as they enter the library. It may include all users of the library, or it can focus on a random sample of these users. This technique monitors user inquiries directly and identifies deficiencies in the collection as well as illustrating users errors in locating materials. Collection deficiencies may take the form of titles not owned or an insufficient number of copies of a given title. The reasons why a user may fail to find a desired item may include: item not owned by the library; item not on shelf due to circulation; item missing or mis-shelved; lack of clear directions for location of materials; lack of correct or complete citation; and user’s error in copying a call number or locating the item on the shelf. The information gathered will identify causes of user failures that should lead to corrective action and changes. The advantages of this technique include: provides immediate, relevant results provides overall view of the size, scope and quality of the collection evaluator sees what the users see reports the failure of real users in finding materials as a by-product identifies non-collection development reasons for user failures and provides data on which changes in library policies and procedures may be based 5 can be readily repeated to measure changes in library performance The disadvantages of shelf availability studies include: subjective and impressionistic; results may be biased if conducted by the librarian who developed that collection or currently selects for it depends on the cooperation of users some materials may not be on the shelf Designing and carrying out the study is time-consuming and difficult Does not identify the needs of nonusers Simulated Use Studies Citation Studies. Citation analysis consists of counting and/or ranking the number of times documents are cited in footnote references, bibliographies, or indexing and abstracting tools and comparing those figures. It is assumed that items that are relatively heavily cited are likely to be used more than those that are cited little or not at all. This technique is similar to the collection-based “List checking,” but here emphasis is on how many times an item is cited to establish relative importance. Citation studies may be used in a variety of situations, but recently their focus has been to develop core lists of primary journals and to identify candidates for cancellation or storage. Empirical data have repeatedly shown that, in many subjects, a relatively small number of “core” primary journals contain a substantial portion of the journal literature bearing on that subject although the proportion varies from one discipline to another. The rest of the literature is scattered throughout a large number of secondary journals. Ranked lists of journals may be used in the development and management of journal collections. This technique is most applicable to research or special collections in university or special libraries. It can be characterized as a specialized form of list checking, in which the lists are created by the evaluator from scholarly books and articles. Citation lists can be more specific and current than published lists, but citation analysis is timeconsuming (less so with a computer) and labor intensive. If your collection is broad, this probably be not a useful method. Procedures sources of citations include dissertations, theses, scholarly and specialized books and articles, special reports, works by best authors in the field, reference tools, and electronic databases determine the sampling method compile list check against library holdings tabulate and analyze results integrate findings with results of other techniques to determine the collection level The advantages of citation studies include: data are easily arranged into categories for analysis method is sufficiently simple that it can be employed repeatedly timely and current: identifies changing trends in the published literature citations could be computer generated: lists can be compiled efficiently and rapidly utilizing online databases frequently used to develop core lists of primary journals can help identify candidates for cancellation or storage The disadvantages of this technique include: time consuming and labor intensive susceptible to popular trends it is difficult to select the source items that will reflect the subject studies or the local user needs subareas of one discipline may have different citation patterns from the general subject research patterns of some disciplines do not lend themselves to citation studies the inherent time lag in citations will not reflect changes of emphasis in disciplines and/or the emergence of new core journals citations do not follow consistent bibliographic standards citation analysis in isolation is a questionable measure for collection development decisions Document Delivery Tests. This carries the citation study a step further, in that it determines not only whether the library holds a certain but, in addition, whether the item can be located and how long it takes to do so. Document delivery tests assess the capability of the library to provide users with the items they need at the time they need them. This technique is also similar to the shelf availability study, but searching is done by library staff rather than users. The most frequent approach is to compile a list of citations that are presumed to reflect the information needs of the users of the library. The test determines both the number of items owned by the library and the time required to locate a specific item. Essentially this technique simulates users walking into the library and each user looking for a particular item. The advantages of the technique include: provides objective measurements of ability of collection to satisfy user needs data can be compared between libraries if identical citation lists are used The disadvantages of document delivery tests include: it is difficult to compile a list of representative citations since library staff perform the searches, the test understates the problems encountered by users, such as user error in locating materials to be meaningful, results require repeated tests or comparisons with studies conducted in other libraries When planning a collection evaluation project, it is important to carefully define the goals for the program, choose the most appropriate methods to be used, and establish what information is needed. An evaluation can be fully comprehensive or it can focus on specific areas, depending on the library’s needs and the resources available to carry it out (evaluations can be expensive!). It can be tempting to gather all sorts of information because it seems interesting, but it may be useless if it does not fit into the parameters of the project. Be sure that everyone participating in the project understands what is expected and when tasks should be completed. There is no single, best way to evaluate a particular collection. Usually, an effective evaluation uses a combination of techniques to gather two kinds of data: quantitative (including numbers, age, and/or use statistics) and qualitative (such as list checking). The type of data useful for evaluation depends on the purpose and mission of the library. For example, a library that wants to provide many varied titles might compare its acquisition rate to annual publishing output, and might look at titles held per capita. If the library has very limited space and must keep growth to a minimum, data on turnover rates (how often items are circulated), acquisitions, withdrawals (weeding) will be essential. A library that focuses on popular works would want information on circulation and in-house use per capita. Some Recommended Lists, Best Books, and Core Collections Retrospective Lists Books for College Libraries: A Core Collection of 50,000 titles. 3rd ed. Chicago, Il.: Association of College and Research Libraries, 1988; 6 vols. This six-volume set devoted to broad disciplines (humanities, history, social sciences, etc.), it recommends a core collection of about 50,000 titles for undergraduate libraries. No annotations, just basic cataloging information. 6 Choice’s Opening day collection. Fiction Catalog Guide to reference books. 11th ed. Robert Balay, editor. ALA) Covers some 16,000 reference titles for medium-sized and large libraries. Annotations for each title are included. College Library Book Selection Conference, Cagayan de Oro City. Basic books for a college library The Reader’s Adviser: A Layman’s Guide to Literature, 13th ed. Edited by Fred Kaplan. New York: R.R. Bowker. 198688. 6 vols. First published in 1921 as The Bookman’s manual, it lists titles that should be in “modestly sized libraries. Generally reliable listing of books with annotations. Subject Bibliographies Baxter, Pam M. Psychology: a guide to reference and information sources. Englewood, Co., Libraries Unlimited, 1993. Coman, Edwin T. Sources of Business Information. Deason, Hilary J., ed. The AAS Science book list. Washington, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1959. Patricia A. Meelung. Selection of materials in the humanities, Social Sciences and Sciences. Beth Shapiro and John Waley. Selection of library materials in applied and interdisciplinary fields Alfred N. Brandon. Selected list of books and journals for the small medical library Serials William Katz. Magazines for libraries Standard periodical directory Ulrich’s International Periodicals Directory Serials directory (EBSCO) Gale directory of publications and broadcast media (Gale Research) Loke, Wing Hong. A guide to journals in psychology and education. Metuchen, N.J., The Scarecrow Press, 1990. Audiovisual Materials Media digest NICEM (National Information Center for Education Media) indexes Index to overhead transparencies Index to educational audio tapes Index to educational slides Index to educational video tapes Microforms Guide to microforms in print National register of microform masters Microform review CD-ROMS Bosch, Sstephen, ed. Guide to selecting and acquiring CD-ROMS, software and other Electronic publications. ALA, 1994. Jasco, Peter. CD-ROM, software, dataware and hardware: evaluation, selection and installation. Libraries Unlimited, 1992. Dewey, Patrick R. 300 CD-ROMs to use in the library: description, evaluations, and practical advice. ALA, 1996. Database: magazine of electronic database reviews Online and CD-ROM review Current Reviews Booklist. Publishes positive reviews of new titles for public and school libraries Choice Critical evaluation of new books of particular interest to academic libraries Library Journal The book review section gives practical evaluation of current titles Book Review Digest Compilation of citations and summaries of new books