Rhetorical distance revisited

advertisement

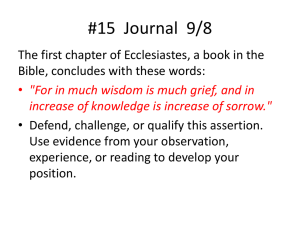

Rhetorical Distance Revisited A pilot study Christian Chiarcos1 Department of Linguistics Applied Computational Linguistics University of Potsdam chiarcos@ling.uni-potsdam.de Olga Krasavina2 Department of Linguistics Humboldt University of Berlin krasavio@rz.hu-berlin.de Abstract We present a general parametrized framework to implement current approaches on referential accessibility in discourse whose parameters are to be trained on coreference and rhetorically annotated corpora. The structuring of discourse plays an important role in use of anaphoric devices. The results obtained by B. Fox (Fox 1987) suggest strong interaction between the embedding of utterances into discourse structure and anaphoric accessibility. Furthermore, the effect of several cues indicating discourse organization has been proved empirically (Givόn 1990:374). Recently, this effect was questioned (cf. Tetreault and Allen 2003). Their results, however, can be attributed to either objective irrelevance of discourse structure on intersentential anaphora or to a need of a more fine-grained empirical analysis. Moreover, theories claiming the importance of discourse structure differ with respect to their assumptions on discourse structuring and its limiting force on the search for the antecedent. We focus on three proposals – the stack model (Grosz and Sidner 1986), veins theory (Cristea 1998), and the rhetorical distance approach (Kibrik 2000). A general framework for theories of intersentential accessibility in discourse is outlined: A minimal set of parameters as a general framework is proposed. The theories are reconstructed on the basis of the parameters as different configurations, following the lines of Chiarcos and Krasavina (2005b). A pilot study for comparative empirical evaluation is presented, using the Potsdam Commentary Corpus (Stede 2004), a German newspaper corpus. The interaction of rhetorical and referential distance is analysed, emphasizing the effect of rhetorical distance on long-distance anaphora. 1 Accessibility in discourse 1.1 Motivation The impact of discourse structure on anaphora has previously been noted, cf. Fox (1987). However, discourse structure per se has been a controversial issue until now. Currently, there are works suggesting that there is no hierarchical structure in some discourse genres (Sibun 1992), that this structure is domain-specific (Mann and Thompson 1988, Webber et al. 2003), or that it is a surface phenomenon induced by local associations (Britton 2001). Other proposals admit the overall importance of hierarchical organization of discourse, but interpret it differently. So there are several theories positing quasi-syntactic rules at the discourse level, 1 2 Christian Chiarcos’ work has been supported by the DFG (German Research Foundation), GRK 275, project number 5220 8303. Olga Krasavina’s work has been supported by grant #03-06-80241 from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research. i.e. veins theory [VT] (Cristea et al. 1998), the stack model (Grosz and Sidner 1986), and – similar to the latter – the right-frontier constraint (Polanyi 1988, Webber 1991, Asher 1993). Different approaches disagree regarding which entities have to be considered as accessible and inaccessible. Here, we focus on the production (generation) perspective, rather than interpretation (anaphora resolution) perspective. Therefore, we bring three theories, Grosz and Sidner 1986, Veins Theory (Cristea 1998) and the rhetorical distance approach (Kibrik and Krasavina 2005) to a common ground, replacing the binary accessibility criterion by graduate measurement using the notion of rhetorical distance. The predictive force of these theories is evaluated on the corpus data: Potsdam Commentary Corpus (Stede 2004), a German newspaper corpus. 1.2 Accessibility and distance One of the main linguistic constraints on the use of pronouns is referential distance (RefD). The term originates from Givόn (1983). It is a measurement which assesses "... the gap, in number of clauses backward, between the referent's current text-location and its last previous occurrence" (Givόn 1995:352). RefD has been used as one of several heuristic measures of topicality in numerous inquiries, especially of such phenomena as voice, word order and anaphora - processes all infuenced by mental activation state of discourse referents (e.g. Jacennik and Dryer 1992). It has been applied in corpus and psycholinguistic studies (Ravnholt 1996, Mitkov 1998), machine translation, anaphora resolution and summarization studies. There are observations about correlations of RefD and other factors, e.g. the type of anaphoric relation – "direct or indirect, object or event-based" (Ravnholt 1996). By far, RefD remains the most commonly accepted method of measuring distance in discourse. The concept of purely referential distance was criticized – mostly because of the structures under consideration. Givόn considered clauses, but in fields of practical application, such as anaphora resolution, utterances and even words were considered (Walker 1998, Strube 1998). Besides this, the existence of trans-sentential segments has been emphasized, thus giving rise to notions of “structural distance” (Ariel 1991). In her application of this previously rather vaguely defined concept, Fox (1987) concluded: “It is not simple distance that triggers the use of one anaphoric device over the other. Rather, it is the rhetorical organisation of that distance that determines whether a pronoun or a full NP is appropriate.” 1.3 Rhetorical Structure Theory in a nutshell Our study builds on the framework of RST, Rhetorical Structure Theory (Mann and Thompson 1988), a descriptive framework for discourse-structural analysis of text. RST relies on the notion of text spans (discourse segments) as constituents of discourse. These are connected by several schemata according to the following principles (Mann and Thompson 1987, p. 7f.): completeness: The set contains one schema application that contains a set of text spans that constitute the entire text. connectedness: Except for the entire text as a text span, each text span in the analysis is either a minimal unit or a constituent of another schema application of the analysis. uniqueness: Each schema application consists of a different set of text spans, and within a multi-relation schema each relation applies to a different set of text spans. 2 Figure 1. Example of a rhetorical tree (Fox 1987) adjacency: The text spans of each schema application constitute one text span. Taken together, these principles ensure RST analyses to be trees with text spans (discourse segments) interpreted as nodes. Then, we refer to a text span consisting of several subconstituents their parent, with the sub-constituents being its children. Accordingly, parents are located above their children in the graph. A central aspect of RST is the investigation of nuclearity in discourse, i.e. the asymmetries between the text spans that make up a more complex structure. Some elements, called nuclei, are more important to the writer’s purpose, less easy to substitute and more necessary for the understanding of a text. Unlike nuclei, satellites can be replaced without any significant change to the text function. They depend in their meaning on other elements. According to their nuclearity, two basic prototypes of schemata are distinguished: mononuclear (subordinating) rhetorical relations with one nucleus and one satellite, multinuclear (coordinating) rhetorical relations with several nuclei, but not satellites. Minimal text spans, the terminal nodes of the tree, are referred to as elementary discourse units (EDUs) here. EDUs are usually clauses (cf. Carlson et al. 2003). An example tree is given in Figure 1, with three EDUs, A, B and C, where A and B form, connected by a CIRCUMSTANCE relation, a larger discourse segment A-B. In turn, A-B and C are connected by an EVIDENCE relation. 3 1.4 The impact of discourse structure on anaphora Fox (1987) admits that under short distances (1-2 clauses) between a pronoun and its antecedent, pronouns are mostly predicted by referential distance. However, not all types of pronouns can be explained this way. Rather, the hierarchical structure of discourse seems to affect the usage of pronouns. The tree in Figure 1 is an example of a “return-pop”, i.e. a type of discourse tree, where a given proposition has some relation to the proposition on the upper level of the discourse tree, rather than to the immediately preceding proposition. While B is sequentially closer to C than A, it can be accessed discourse-structurally only by making a detour over A. So, C is closer to A discourse-structurally. This can explain occurrences of pronouns, which refer to clauses other than immediately preceding ones. Furthermore, Fox shows that the approach suggested by Givόn (1983) produces overgeneration, because the influence of the discourse-structural devices such as the beginning of a new rhetorical unit is ignored. In the latter case, devices of higher explicity, i.e. full descriptions, rather than pronominal forms, are preferred. The most prominent family of approaches to consider is based on the right-frontier constraint (Webber 1991, Asher 1993) that formulates a necessary condition for pronominal reference (or anaphoric relations in general): anaphoric reference is possible only to those nodes that directly dominate (or structurally precede) the actual segment. A classical formulation has been given with the focus-stack model by Grosz and Sidner (1986). Here, anaphoric accessibility is a consequence of the interplay of attentional and intentional structure: The intentional structure induces a global hierarchical structuring of the text, where different discourse segments are related by either coordinating SATISFACTIONPRECEDENCE or subordinating DOMINANCE relations, both are mono-directional. The attentional structure then is defined as a stack induced by the intentional structure. It comprises the potential antecedents of anaphors occurring in the current segment that are grouped together in ”focus spaces” where each focus space is associated with a dominating (or the actual) segment. Whenever a new segment is opened, the actual focus space is pushed into the stack, if it is closed, it is popped out. Thus, focus spaces are ranked according to the number of DOMINANCE relations between their segment and the actual one. Accessibility of a discourse segment for antecedent search depends on the depth of this fragment in the stack. Projected to the RST tree, the DOMINANCE relation can be interpreted as subordinating relations in the RST, as suggested by Moser and Moore (1996). Another important theory is Veins Theory (Cristea et al. 1998). It states that the accessibility of antecedents depends on so-called “veins” computed by special rules applied on an RSTlike graph. The status of a discourse unit – nucleus or satellite – plays the determining role, but the relative order of discourse segments is taken into account as well. The type of rhetorical relation is of no importance at all. Against the right-frontier proposals, veins theory is directly built on RST. There, a crucial difference, as opposed to Grosz and Sidner (1986) is the existence of left satellites that lack a formal representation in discourse structure. Kibrik (2000) proposed a measurement of rhetorical distance, which is calculated using the shortest path from an anaphor to its antecedent along the rhetorical tree. Although referential 4 distance also plays a certain role, Kibrik claims that rhetorical distance is a stronger factor licensing the use of pronouns vs. definite NPs. The theories presented so far share important common insights: Depending on the rhetorical structure, an accessibility domain is constructed (sequence of dominating segments in stack model, veins, paths). An EDU is regarded as accessible iff. it is included in this domain. The relative degree of accessibility of an antecedent-EDU can be calculated considering the shortest path between an anaphor and a potential antecedent. The distance between an anaphor and its potential antecedent on this path corresponds to the likelihood that it serves as an antecedent. We suggest that theory-dependent accessibility judgements can be modelled by assigning weights to edges on this path depending on their respective types. Thus, such edge weights are interpreted as parameters of a generalized framework of discourse-structural accessibility. We provide a minimal set of parameters and show how to reconstruct the theories as different configurations. The configurations are compared and generalizations are proposed. Finally, we present a pilot study on the German newspaper corpus – the Potsdam Commentary Corpus (Stede, 2004). 2 A parametrized framework 2.1 Trees and paths Our approach builds on the following basic conventions: We consider binary trees. A node n CONTAINS a referring expression o if it is an EDU and subsumes the expression, or o if one of n’s direct children contains it. We treat EDGES as elementary building blocks of path construction. We consider vertical edges only, i.e. relations between a child and a parent node in the rhetorical tree. No direct links between different child nodes are allowed. We say, an edge POINTS FROM one node n1 TO another node n2 if o n1 is the child node of n2 and n1 contains the anaphor (ASCENDING edge) or o n1 is the parent node of n2 and n2 contains the antecedent (DESCENDING edge). The underlying intuition is to construct an acyclic path, i.e. a sequence of edges, pointing from one EDU A containing the anaphor to another EDU B containing a potential antecedent, henceforth represented as A → B. Edges not on the path, i.e. pointing to/from text spans that contain neither antecedent nor anaphor, are excluded. In the following section, we sketch a minimal taxonomy of edge types that provides parameters for the general framework. Note that we ignore the type of relation beyond the distinction of mononuclear (asymmetric) and multinuclear (symmetric) relations. 5 2.2 Parameters The intention of this paper has been to propose a minimal set of parameters as a base for the comparison of previous approaches. This restriction is even more important for empirical studies. Since corpora annotated with discourse structure and coreference are rare and small, the number of parameters has to be minimized to prevent sparse-data problems. In addition to the distinction between ascending and descending edges in the path to be constructed, we suggest the following parameters to define necessary distinctions among edges: whether a relation is mononuclear or multinuclear whether the child node serves as satellite or nucleus of the dominating node (for a multinuclear relation, all child nodes are defined as nuclei) whether the child node is left-most or right-most of the children (we assume binary trees). As a convention, these four features of edges are encoded by edgelabels in the following way: the first two letters denote nuclearity of the underlying discourse relation, i.e. mo (mononuclear) or mu (multinuclear) the third letter denotes the sequential position of the child node, i.e. l (left) or r (right) the fourth letter denotes the type of the child node, i.e. s (satellite) or n (nucleus): fifth letter denotes the direction of the edge, i.e. whether it is ascending a or descending d For example, mulnd denotes a multi-nuclear discourse relation, with the antecedent (descending) in the left-most (nuclear) child-node, while morsa corresponds to a mononuclear discourse relation, with the anaphor (ascending) in the satellite that is the right-most child node. Then, a path in a rhetorical tree can be represented as a sequence of edge labels, beginning at the position of an anaphor and ending at the EDU containing the antecedent. RHETORICAL DISTANCE (RhetD) between referential expressions in two EDUs is then defined as the weighted sum of occurrences of labels in the path between them. A theory of path(α,β) = (m molna, morsa, mol nd, molnd, molnd) rhet-dist(α,β) = wmolna + wmorsa + wmolnd + wmolnd + wmolnd acc(α,β) iff. rhet-dist(α,β) < τ Figure 2: Example analysis 6 accessibility can then be represented by the choice of weights and threshold. An EDU B is accessible from another EDU A if its RhetD is below an accessibility threshold τ: accessible(A,B) iff. rhet-dist(A,B) < τ The higher the RhetD of a potential antecedent node is, the lower is its relative degree of accessibility. 3 Reconstructing previous attempts Here, we present a set of parameters that is capable of achieving locally optimal approximations and is thus adequate with respect to the stack model, veins theory and Kibrik and Krasavina’s concept of rhetorical distance. Finally, a minimal set of parameters is used as a basis for the comparative evaluation of the theories. We illustrate the adequacy of this proposal by assigning different weightings to our set of parameters as configurations which generate the necessary distinctions. 3.1 Grosz and Sidner (1986) Previous interpretations of Grosz and Sidner’s model in RST terms (Moser and Moore 1996, Tetreault and Allen 2003) agreed on the rough correspondence between RST-nuclearity and DOMINANCE by Grosz and Sidner (1986), thus equating DOMINANCE relations with mononuclear (subordinating) RST relations and SATISFACTION-PRECEDENCE with multinuclear (coordinating) RST relations. This analysis is consistent with the partial mapping from Grosz and Sidner’s model onto RST that has been suggested by Moser and Moore (1996:414), where embedded segments in Grosz and Sidner (1986) are analyzed as satellites in RST. This partial mapping has been extended by Marcu (2000:527f.) who proposed an isomorphic mapping between DOMINANCE and RST-subordination, and a (mono-directional) homomorphism transforming SATISFACTION-PRECEDENCE into multinuclear relations. Nevertheless, RST structures and those assumed by Grosz and Sidner differ with respect to their granularity. So, it seems that an interpretation of Grosz and Sidner’s discourse structure and rhetorical structure in the sense of Mann and Thompson can be problematic. Generalizing over these insufficiencies, we summarize the Grosz and Sidner (1986) model as follows:3 ascending from a nucleus and descending into a nucleus is always possible ascending from a satellite is always possible descending into a satellite node is not permitted Then, the Grosz and Sidner (1986) configuration assigns every descending satellite edge (i.e. molsd, morsd) the weight w molsd, morsd = 1, everything else the weight 0. If we now compare the values calculated for rhetorical distance in the Grosz and Sidner (1986) – configuration to the original binary criterion of accessibility, we find that an EDU is accessible iff. its rhetorical distance is lower than 1, otherwise it is not. So, the accessibility threshold τ is set to 1. Note that Grosz and Sidner’s model cannot account for left satellites according to Cristea et al. (1998). One could assume that left satellites in RST are not in a DOMINANCE relation, but in a SATISFACTION-PRECEDENCE relation or part of the same discourse segment the nucleus belongs to as well. However, this interpretation conflicts with Marcu’s and Moser/Moore’s view. With respect to the situation of n-ary branching relations, where sequential order among satellites does not necessarily imply SATISFACTION-PRECEDENCE relations, another solution is to apply Marcu’s mapping onto left-branching satellites as well, though such configurations could not have been expressed in the original Grosz and Sidner (1986) proposal. 3 7 The vein of the root is its head; Let v be the vein of a non-terminal node with left child L (head hl and right child R (head hr); The vein of L and R is defined as follows: type of relation nuclearity veins of child nodes L R L R multinuclear NUC NUC v v mononuclear NUC SAT v v’ ◦ hr mononuclear SAT NUC v ◦ hr (hl) ◦ v Here, x ◦ y will produce a flat list comprising the heads enumerated in x and y according to their respective linear order; x’ means to remove all elements marked by parentheses from the vein x. Table 1: Veins Theory schematically 3.2 Veins Theory Veins Theory (Cristea et al. 1998) is a generalization of Centering Theory (Grosz et al. 1995) that extends the applicability of centering rules by defining larger domains of accessibility within a discourse tree. These domains, VEINS, are derived as follows: 1. In a bottom-up manner, a head is assigned to every node in the tree (a) if an EDU is a terminal node, its head is its unique ID label, (b) if an EDU has one nuclear child node (mononuclear node), its head is the head of its nucleus (c) if an EDU has several nuclear child nodes (multinuclear node), its head is the concatenation of the heads of its nuclear children. 2. Then, the vein is calculated top-down using the heads derived so far, see Fig. 2 3. For an EDU with label u, all EDUs that are in the vein of u and precede u sequentially are defined as accessible. The rules can be interpreted as follows: Nuclei are always accessible (m mulna, murna, mulnd, murnd, molna, morna, molnd, mornd). Right satellites are inaccessible as antecedents (m morsd). Left satellites (m molsd) are accessible only from the subtree dominated by the corresponding nucleus, but not from right-branching satellite nodes (m morsa). Thus, the combination of molsd and morsa has to be prohibited. Further, multiple morsa edges are allowed, while multiple molsd edges are not. We assign molsd a large constant as a weight and morsa a small one, with wmolsd + wmorsa as the threshold of accessibility; morsd is always inaccessible, thus, it must be given a weight larger than wmolsd + wmorsa. Every other type of edge is accessible. A limitation of our proposal is its local character. As an example, descending into a satellite is always impossible except in the root node. To approximate this behaviour, we assign every descending edge a small additional weight (smaller than wmorsa). 8 3.3 Kibrik’s measurement of rhetorical distance The underlying idea in Kibrik’s approach is that given a pair of EDUs with one containing a potential antecedent and the other one containing a potential anaphor, a path is constructed pointing from the potential anaphor to the potential antecedent. Then, rhetorical distance is given by the number of transitions on this path. In contrast to our proposal, these paths are not directly based on the rhetorical structure a text has, but are taken from a simplified ”transition graph”. For mononuclear relations, a transition is given if both nucleus and satellite child are on the path. Thus, mononuclear edges from/to nuclei do not contribute to rhetorical distance (wmolna, molnd, morna, mornd = 0) whereas mononuclear edges from/to satellites are counted (wmolsa, molsd, morsa, morsd = 1). The handling of multinuclear relations is slightly more complex. For the transformations needed there, Kibrik (2000) proposed certain rules which resulted in a heavy transformation of the tree. In a later paper (Kibrik and Krasavina 2005), some modifications were suggested. The method can be summarized in two rules: move along the graph towards the nearest antecedent and count how many horizontal jumps you make when one jump penetrates into a symmetrical structure or makes a step out of it, a penalty of 0.5 is added As a result, 3.4 satellites are less accessible than nuclei in mononuclear relations nuclei in multinuclear relations are less accessible than nuclei in mononuclear relations. Comparison As a first result, we can now compare our reconstructions of the three theories. With respect to the parameters all theories have in common, we obtain the configurations in Figure 3. Reinterpreting the absolute weights as partial orders (cf. Fig. 4), we find – not unsurprisingly – a great deal of compatibility, especially among less accessible relations, morsd, molsd, indicating that descending into a satellite is quite a costly operation. Additionally, ascending from the nucleus of a mononuclear relation (m molna, morna) seems to be least problematic, with multinuclear relations being intermediate. Generally, ascending is assumed to be easier than descending, cf. Grosz and Sidner (1986), according to whom this restriction is the core effect of discourse structure on referential accessibility. For comparison of the approaches, theory-specific parameters can be safely ignored. The stack model in its original formulation by Grosz and Sidner cannot be applied to RST-like discourse structure in a straight-forward way. However, our adaption is consistent with previous proposals (Mooser and Moore 1996, Marcu 2000, Tetreault and Allen 2003). 9 Veins Theory involves both global and local optimization that is not covered completely by the minimal set of parameters applied so far. In contrast to the limitations with respect to Grosz and Sidner, this restriction seems to be intrinsic to an approach that does not take the relative order of edges into consideration. Thus, we achieve a local approximation only. Whereas an algorithm using pairs of edges is likely to perform better, we restrict our attention to the minimal set of parameters for the purpose of comparison. All theories are compatible with the ranking of edge labels illustrated in Fig. 4. RST structure edge G&S VT K&K molna 0 0 0 molnd 0 0.01 0 molsa 0 0 1 molsd 1 1 1 morna 0 0 0 mornd 0 0.01 0 morsa 0 0.05 1 morsd 1 2 1 mulna 0 0 0.5 mulnd 0 0.01 0.5 murna 0 0 0.5 murnd 0 0.01 0.5 threshold τ<1 τ < 1.05 n.a. Figure 3. Edge labels and their corresponding weights, according to Grosz and Sidner (1986), Cristea et al. (1998) and Kibrik and Krasavina (2005). 10 morsd ≥ molsd morsd higher RhetD (less accessible) ≥ morsa ≥ mulnd murnd ≥ mulna murna ≥ morna molna lower RhetD (highly accessible) The effect of molsa, molnd and mornd is controversial. Figure 4. Rankings of edge labels 4 Towards an empirical evaluation Having provided a general framework, we perform a comparative analysis of the theories with respect to their predictive power, namely on the use of full descriptions (proper names, definite descriptions4) and pronouns (personal pronouns, possessive pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, pronominal adverbs) on 134 texts from the Potsdam Commentary Corpus (PCC, Stede 2004). The PCC is a collection of German newspaper commentaries annotated for morpho-syntax (using the TIGER format, cf. Brants and Hansen 2002), coreference (Chiarcos and Krasavina 2005b), rhetorical structure (Reiter and Stede 2003), information structure (Götze 2003), and discourse connectives (Stede 2004). As the focus of theories on discourse-structural accessibility lies on anaphoric references beyond the current clause. We excluded trivial cases from consideration, i.e. when anaphor and antecedent occur in the same EDU. Thus, precision and recall can only be compared relative to each other only, rather than with respect to the overall data.5 The results obtained so far are preliminary, but give hints on directions for further research. One of the most important results was that distance measures alone cannot sufficiently account for the distribution of referring expressions (This is illustrated by rather nonsatisfying results for recall and precision, cf. Tab.2 and 3). Still, this is not unexpected, as a low degree of rhetorical or referential distance is usually assumed to be a necessary condition for pronominalization, but not a sufficient one. Rather, both veins theory and stack model are closely interrelated with Centering Theory, where additional constraints on the use of pronouns are formulated in terms of surface properties of the antecedent (Grosz et al. 1995). Similarly, Kibrik (2000) considered other factors affecting the use of pronouns as well. However, we leave the task to investigate the interaction between surface cues, referential distance and different views on rhetorical distance for forthcoming research. Instead, we focus on the impact of rhetorical distance alone. 4.1 Predicting referential accessibility For the investigation of referential accessibility in general, we distinguish two major classes of anaphors, full descriptions and pronouns and compare the different configurations of rhetorical distance in terms of 4 Note that ''description'' is used in its syntactic sense, here. It denotes noun and prepositional phrases not being pronominal, but involving at least one nominal lexeme. 5 For pronominalization, both precision and recall are higher due to the overwhelming majority of pronouns among short-distance references. 11 precision (relative portion of correctly predicted expressions from predicted expressions); recall (relative portion of correctly predicted expressions from originally used expressions); f-measure (the harmonic mean of recall and precision); χ2-test to test against the null hypothesis of independence. Since Kibrik and Krasavina's model of rhetorical distance does not provide an accessibility threshold, we applied different values of τ. Besides the theories, we tested a baseline defined as the path length, i.e. the number of edges on the path, again with different τ-values. G&S VT K&K τ = 1.0 τ = 1.5 τ = 2.0 τ = 2.5 τ = 3.0 τ = 3.5 τ = 4.0 baseline τ = 2.0 τ = 3.0 τ = 4.0 τ = 5.0 τ = 6.0 correct predicted 173 209 total predicted 418 523 total recall precision f χ2 correct 282 61,35% 41,39% 49,43% 23.62, p<0.01 282 74,11% 39,96% 51,93% 38.01, p<0.01 17 171 193 234 243 258 261 45 350 413 574 638 733 759 282 282 282 282 282 282 282 6,03% 60,64% 68,44% 82,98% 86,17% 91,49% 92,55% 37,78% 48,86% 46,73% 40,77% 38,09% 35,20% 34,39% 10,40% 54,11% 55,54% 54,67% 52,83% 50,84% 50,14% 0.74, p=0.39 76.37, p<0.01 78.13, p<0.01 58.83, p<0.01 40.03, p<0.01 21.11, p<0.01 14.93, p<0.01 2 114 176 220 244 7 176 341 496 626 282 282 282 282 282 0,71% 40,43% 62,41% 78,01% 86,52% 28,57% 64,77% 51,61% 44,35% 38,98% 1,38% 49,78% 56,50% 56,56% 53,74% 0.04, p=0.85 109.03, p<0.01 98.95, p<0.01 80.29, p<0.01 48.05, p<0.01 Table 2. Predictions as to pronouns (personal pronouns and possessive pronouns) according to Grosz and Sidner (G&S) reconstruction, veins theory (VT) reconstruction and Kibrik and Krasavina (K&K). G&S VT K&K τ = 1.0 τ = 1.5 τ = 2.0 τ = 2.5 τ = 3.0 τ = 3.5 τ = 4.0 baseline τ = 2.0 τ = 3.0 τ = 4.0 τ = 5.0 τ = 6.0 correct predicted 356 287 total predicted 465 360 total recall precision f χ2 correct 601 59,23% 76,56% 66,79% 23.62, p<0.01 601 47,75% 79,72% 59,73% 38.01, p<0.01 573 422 381 261 206 126 103 838 533 470 309 245 150 124 601 601 601 601 601 601 601 95,34% 70,22% 63,39% 43,43% 34,28% 20,97% 17,14% 68,38% 79,17% 81,06% 84,47% 84,08% 84,00% 83,06% 79,64% 74,43% 71,15% 57,36% 48,70% 33,56% 28,41% 0.74, p=0.39 76.37, p<0.01 78.13, p<0.01 58.83, p<0.01 40.03, p<0.01 21.11, p<0.01 14.93, p<0.01 596 539 436 325 219 876 707 542 387 257 601 601 601 601 601 99,17% 89,68% 72,55% 54,08% 36,44% 68,04% 76,24% 80,44% 83,98% 85,21% 80,70% 82,42% 76,29% 65,79% 51,05% 0.04, p=0.85 109.03, p<0.01 98.95, p<0.01 80.29, p<0.01 48.05, p<0.01 Table 3. Predictions as to full descriptions (proper names and definite NPs) according to Grosz and Sidner (G&S) reconstruction, veins theory (VT) reconstruction and Kibrik and Krasavina (K&K). 12 correct predicted total predicted total correct recall precision f χ2 RefD, τ = 1 RefD, τ = 2 RefD, τ = 3 117 247 259 174 462 597 282 282 282 41.49% 87.59% 91.84% 67.24% 53.46% 43.38% 51.32% 66.40% 58.93% 124.26, p<0.01 206.57, p<0.01 111.11, p<0.01 RefD, τ = 1 RefD, τ = 2 RefD, τ = 3 544 386 263 709 421 286 601 90.52% 76.73% 601 64.23% 91.69% 601 43.76% 91.96% Table 4. Referential distance 83.05% 75.54% 59.30% 124.26, p<0.01 206.57, p<0.01 111.11, p<0.01 prn full Surprisingly, it turned out that the baseline (with τ=3 resp. τ =5) outperformed the established theories, closely followed by Kibrik and Krasavina (2005) (τ=2), veins theory reconstruction and stack model. This can be explained by the interaction of rhetorical distance and referential distance, which is outlined in the following sentence. 4.2 Rhetorical and referential distance For our pilot study, we considered sequential antecedents. Under this restriction, RhetD seems to be generally ruled out by RefD, as illustrated in Tab 4. Accordingly, we assume referential distance to be a main determinant of pronoun use in local contexts. Thus, we concentrate on rhetorical distance as a device allowing for pronominal reference where it is unexpected under a purely sequential account. To exclude cases that are more properly explained by short-distance effects, we introduce a bias β to filter out cases with referential distance smaller than β. G&S VT K&K, τ = 1.5 K&K, τ = 2 baseline, τ = 3 baseline, τ = 4 baseline, τ = 5 RefD, τ = 1 RefD, τ = 2 RefD, τ = 3 RefD, τ = 4 RefD, τ = 5 RefD, τ = 6 # prn # full NP RefD bias β β=0 49.43% 51.93% 54.11% 55.54% 49.78% 56.50% 56.56% 51.32% 66.40% 58.93% 55.52% 53.59% 51.36% 282 601 β=1 40.76% 42.22% 45.59% 45.99% 44.53% 47.36% 45.71% n.a. 57.40% 48.30% 44.55% 42.64% 40.41% 165 544 β=2 20.11% 18.34% 21.88% 20.51% 14.29% 18.02% 18.89% n.a. n.a. 14.12% 14.05% 14.92% 14.69% 35 386 β=3 20.80% 20.69% 28.92% 27.72% 20.00% 20.90% 22.86% n.a. n.a. n.a. 10.53% 13.51% 13.53% 23 263 β=4 22.47% 20.00% 32.73% 27.27% 28.57% 30.43% 29.41% n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 14.08% 13.85% 18 196 β=5 20.29% 17.95% 33.33% 26.92% 36.36% 38.89% 28.57% n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 11.11% 13 148 β=6 18.60% 16.33% 28.57% 24.24% 35.39% 34.78% 24.24% n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 9 93 Table 5. Interplay between referential distance (RefD) and rhetorical distance (RhetD). 13 We found that for the use of referring expressions, referential distance is a better predictor of pronouns with antecedents within the last two clauses. This assumption is further supported by the impressive performance of the baseline, with edge labels being ignored, for unbiased data (β = 0). For references beyond this point, i.e. with referential distance larger than 2, rhetorical distance is a better indicator. Curiously, the theories seem to perform similarly (for β =2), though for longer distances, a slight advantage of Kibrik and Krasavina's rhetorical distance might be suspected. The data on long-distance pronominal anaphors is, however, too sparse to draw any definite conclusions at this point, as illustrated by the seemingly better performance of the base-line for pronouns with referential distance greater than 4. So, this effect has to be investigated further using additional corpora from other languages and heterogenuous registers. As we focused on one single corpus consisting of the newspaper texts only, we cannot exclude annotation artifacts. Due to its limited size, the number of long-distance pronouns is too low, so that we could make any commitments. In 134 texts from the PCC, only 35 pronouns (12.4%) can be considered as long-distance anaphors. 4.3 Edges and expressions Another aspect of our study was the comparison of the theories, as to the appropriateness of the parameter weighting. To do so, we abstract over the frequency of edges, consider the likelihood of a type of a referring expression r to occur on the path where a given edge label e is present (Fig. 5) and compare relative differences with respect to the average edge frequency per referring expression (Table 6). Edge labels preferred for long-distance anaphors are excluded. Figure 5. Portion of referring expressons per edge label. 14 morna morsa murna molnd molsd mulnd defnp (+) (–) –– (–) (+) (+) ne = = + (–) + – prn (–) (+) ++ (+) – + Deviation from the average ++ iff. ≥5% + iff. ≥ 2.5% (+) iff. ≥ 0.5% – = iff. strong preference preference slight preference accordingly for dispreferences derivation less than 0.5% Table 6. Referring expressions per edge label: deviation from the average. In Tab. 6, three groups of edge labels can be distinguished. edges with strong preferences (++) for pronouns, but strong dispreference (– –) for definite descriptions murna edges with preference (+) for pronouns, but not for (-,=) for definite descriptions and proper names mulnd edges without any preferences or with slight preferences only morna, morsa, molnd edges with dispreference for pronouns, but (slight) preference for definite descriptions and proper names molsd Thus, a ranking is observable as summarized in Fig. 6. Whereas the results for molsd seems to conform assumptions underlying the theories as reconstructed above, the differentiations made between the more accessible edge types are different from the respective predictions. The higher frequency of murna edges for pronouns than for definite descriptions can be explained by the constraint on the repetition of full NPs at short distances, which results in their substitution by pronouns. Futher, we observe that molsd seems to restrict usage of pronouns, in contrast to molnd and mulnd. Again, this conforms the assumptions of the the stack model (Grosz and Sidner 1986) and veins theory (Cristea et al. 1998), whereas the prediction of Kibrik and Krasavina (2005) is that the patterns of molsa und molsd are identical. molsd > morna, morsa, molnd > mulnd > murna low accessibility full NPs high accessibility pronouns Figure 6. Observed ranking of edge labels. 15 Despite these problems, some predictions with respect to the ranking of edge labels (cf. Fig. 4) could now be verified empirically (see Fig. 6). Especially, it was not clear how molnd is related to other edge labels. It is less accessible in VT reconstruction than mulna and murna, being at the same level as mulnd and murnd. According to Kibrik and Krasavina (2005), molnd is grouped together with molna and morna, thus regarded to be more accessible than murna and mulna. In the data we found that murna seems to be dispreferred for definite descriptions indicating that Kibrik and Krasavina’s treatment of molnd is possibly more appropriate. Besides this, we found that under molsd the choice of definite descriptions is preferred, as predicted. Besides this, we observe that proper names share features of both pronouns and definite NPs. This may be due to the two-fold function of proper names: on the one hand, they serve as a shortcut for unique identification of a referent; on the other hand they can be of high explicity, which relates them to full NPs – the expressions at the lower end at the accessibility marking scale (Ariel 1990).6 This can explain the seemingly higher frequency of murna edges for proper names than for definite NPs (Fig. 5). We suspect proper names are used as a short reference in this case, because the corresponding referents have been sufficiently described in the previous discourse. 4.4 Final remarks Rhetorical distance and referential distance co-operate For short-distance references, we found a strong tendency for referential distance to be a more appropriate predictor of pronominalization. Still, as this seemingly superiority might be due to the restriction to sequential antecedents, not rhetorical ones, a comparative analysis considering the respective rhetorical distance of all antecedents will be performed. However, for long-distance anaphors, RefD is ruled out by RhetD, indicating that two strategies are applied in parallel. Accoding to the greater number of short-distance references performed by pronouns, RefD can be seen as a “default” measurement of referential accessibility, whereas rhetorical distance comes into play in cases of long-distance anaphora. In more technical terms, we suggest the combined application of Walker’s cache model (1996) and Grosz and Sidner’s stack model (and related approaches) side by side. For concrete application, this conforms to Tetrault and Allen’s Grosz and Sidner stack approximation algorithm (Tetreault and Allen 2003), which follows Walker’s (2000) analysis stating that reference can occur between two utterances even if they are split by a segment boundary. Comparative performance of theories of discourse structural accessibility As rhetorical distance effects are observable for long-distance anaphors which make up about 12.41% of pronouns in our corpus, no definite conclusions can be made due to the sparsity of data. Still, it seems that the theories under consideration show a similar performance, ruling out the baseline (i.e. the length of a path). Further, these analyses have to be enriched by the inclusion of other factors such as grammatical role of antecedent, a distinction of types of rhetorical relations, etc. as distance measures formalize necessary conditions for the use of pronouns, but no sufficient ones. 6 For further research, we suggest to emphasize the distinction between short and full names more explicitly. 16 (7.1) (7.2) Figure 7: Critical cases for veins theory reconstruction Accordingly, accessibility is not the only criterion to be considered. Besides this, the effect of interference or ambiguity of reference must be addressed, too, cf. Poesio et al. (2002). Further questions Note that our reconstruction of veins theory is locally adequate only. We find critical cases such as those depicted in the partial trees in Fig. 7. In (7.1), the left-most node (A) is inaccessible from the right-most (D) according to veins theory, whereas in (7.2) it is accessible. However, the number of edge labels on the paths, and thus the calculated rhetorical distance, is identical in both cases. A minimal solution is to mark the neighbourhood of the root node, resulting in a set of 15 parameters (12 normal plus 3 left-descending edges at the root node), but a more intuitive alternative is to assume such locality effects everywhere in the tree. We did not distinguish different kinds of relations, but only different types of structures. It has often been claimed that referential accessibility depends on the semantics of discourse relations, too. An extended set of parameters could be a subject of later inquiries. References Ariel, M. (1990) Accessing Noun-Phrase Antecedents (London: Routledge). Asher, N. (1993) Reference to abstract objects in discourse (Dordrecht: Kluwer). Brants, Sabine and Hansen, Silvia (2002) Developments in the TIGER Annotation Scheme and their Realization in the Corpus, in Proceedings of the Third Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2002), 1643-1649. 17 Britton, B.K. et al. (2001) Thinking about bodies of knowledge, in Sanders, T. et al. (eds), Text Representation. Linguistic and psycholinguistic aspects (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 273– 306. Carlson, L., D. Marcu, and M.E. Okurowski (2003) Building a Discourse-Tagged Corpus in the Framework of Rhetorical Structure Theory, in J. van Kuppevelt and R. Smith (eds), Current Directions in Discourse and Dialogue (Dordrecht: Kluwer), 85–112. Chiarcos, Ch. and O. Krasavina (2005a) Rhetorical Distance revisited: A parametrized approach, in Proceedings of Workshop in Constraints in Discourse, Dortmund, 3-6 June 2005. Chiarcos, Ch. and O. Krasavina (2005b) Annotation Guidelines. POCOS – Potsdam Coreference Scheme. Available on-line from http://amor.cms.huberlin.de/~krasavio/annorichtlinien.pdf (12/06/2005). Cristea, D., N. Ide, and L. Romary (1998) Veins Theory. A model of global discourse cohesion and coherence, in Proc. 36th Ann. Meeting of the ACL, 281–285. Fox, B. (1987) Discourse Structure and Anaphora (Cambridge: CUP). Givόn, T. (1983) Topic continuity in discourse (Amsterdam: Benjamins). Givón, T. (1990) Syntax. A functional-typological introduction (Amsterdam: Benjamins). Götze, M. (2003) Zur Annotation von Informationsstruktur. Diploma thesis, University of Potsdam. Grosz, B. and C. Sidner (1986) Attention, intentions, and the structure of discourse. Computational Linguistics 12(3):175–204. Grosz, B., A.K. Joshi, and S. Weinstein (1995) Centering: A framework for modelling the local coherence of discourse. Computational Linguistics 21(2):203–225. Jacennik, B. and M. S. Dryer (1992) Verb-Subject Order in Polish, in D. Payne (ed.), Pragmatics of Word Order flexibility (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 209-241. Kibrik, A. (2000) A cognitive calculative approach towards discourse anaphora, in Proc. Discourse Anaphora and Anaphor Resolution Colloquium (DAARC’2000). Kibrik, A. and O. Krasavina (2005) A corpus study of referential choice. The role of rhetorical structure, in Proceedings of DIALOG’05, Zvenigorodsky, Russia. Mann, B. and S. Thompson (1987) Rhetorical Structure Theory: A Theory of Text Organization. Research Report. USC. Mann, B. and S. Thompson (1988) Rhetorical Structure Theory. TEXT 8(3):243–281. Marcu, D. (2000) Extending a formal and computational model of Rhetorical Structure Theory, in Proc. 18th Int. Conf. on Computitional Linguistics (COLING’2000). 18 Mitkov, R. et al. (2000) Coreference and Anaphora: Eveloping Annotating Tools, Annotated Resources and Annotation Strategies, in Proceedings of Discourse Anaphora and Anaphor Resolution Colloquium (DAARC 2000). Moser, M. and J. Moore (1996) Toward a synthesis of two accounts of discourse structure. Computational Linguistics 22(3):409–419. Poesio, M. di Eugenio,B., Keohane,G. (2002) Discourse Structure and Anaphora: An Empirical Study, University of Essex, NLE Technical Note TN-02-02. Polanyi, L. (1988) A formal model of the structure of discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 12:601–638. Ravnholt, O. (1996) Grammatical Cues and "Referential Distance" in the Retrieval of Antecedents in Discourses, in S. Botley, J. Glass, T. McEnery and A. Wislon (eds.), Proceedings Discourse Anaphora and Resolution Colloquium (DAARC'96) Reiter, D. and Stede, M. (2003) Step by step: Underspecified markup in incremental rhetorical analysis, in Proceedings of the 4th international workshop on Linguistically Interpreted Corpora (LINC-03). Sibun, P. (1992) Generating text without trees. Computational Intelligence 8 (1):102-122. Stede, M. (2004) The Potsdam Commentary Corpus, in Proc. of the ACL-04 Workshop on Discourse Annotation. Strube, M. (1998) Never look back. An alternative to Centering, in Proc. ACL, 1251-1257 Tetreault, J. and J. Allen (2003) An empirical evaluation of pronoun resolution and clausal structure, in Proc. 2003 Int. Symp. on Reference Resolution and its Applications to Question Answering and Summarization, 1–8. Walker, M.A. (1998) Centering, anaphora resolution, and discourse structure, in M. A. Walker, A. K. Joshi, and E. F. Prince (eds.) Centering in Discourse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 401–435. Walker, M.A. (2000) Toward a model of the interaction of centering with global discourse structure. Verbum. Webber, B. (1991) Structure and ostension in the interpretation of discourse deixis. Natural Language and Cognitive Processes 2(6):107-135. Webber, B. et al. (2003) Anaphora in discourse structure. Computational Linguistics 29(4): 545–587. 19