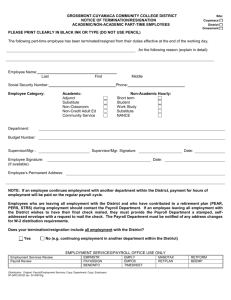

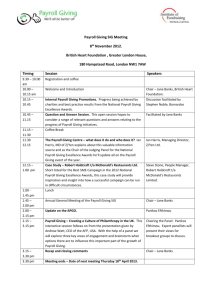

Box 1: Removal of “Ghost Workers in Uganda

advertisement

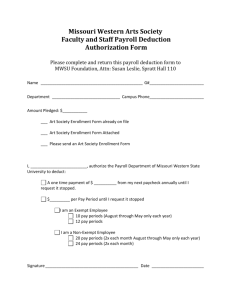

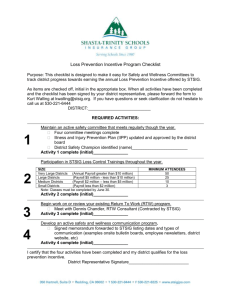

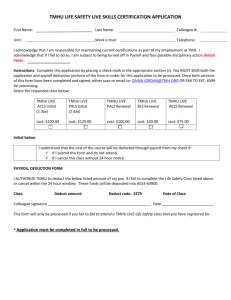

Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Part A: Introduction In the past four decades, when most African countries have been independent, three distinct epochs on the issues of personnel costs in public expenditure may be generally discerned. The period spanning 1960s to mid-1980s was characterised by rapid growth in public sector employment and personnel costs. The mid-1970s to mid-1980s were characterised by a rapid decline in public service pay and collapse of the systems for personnel management and control. The 1990s has been a decade of efforts to manage and control personnel costs. This paper focuses on the good practices lessons of experience in this decade of reform efforts in four East and Central Africa countries, i.e. Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia (select countries). Before presenting the “good practices” however, it is considered useful to provide an overview of pertinent issues. Therefore, the next section presents the background and context for good practices in the control and management of personnel costs. The last section describes the good practices. Part B: Background and Context Discussion of good practices in controlling the managing/personnel costs in Africa countries should be in the context of the following: rapid expansion of government employment and personnel costs from 1960s and 1980s; rising total personnel costs and declining compensation from the 1970s; personnel numbers are falling but wage bills are rising in the 1990s; comparatively Africa countries have the lowest Government employees per capita; significance of collapse of systems of management and control; not-so successful initiatives; and promising good practices yet to be undertaken. Rapid Expansion of government employment and personnel costs: 1960s to 1980s Rapid growth in public sector personnel costs from the 1960s to 1980s was reflected in increases in both the numbers of employees and real pay in the sector. Between mid-1960s and mid-1980s, the total number of central government employees more than trebled in these countries (see Table 1). Two basic factors underpinned this rapid growth in public service numbers. First, the expansion in numbers was driven by the felt need to recruit staff to support growth in basic social services, especially education and health, these were benefits expected from the Government following independence. Second, the governments undertook to the role of employer of last resort for increasing numbers of school leavers in a period or rising urban unemployment. Table 1: Rise in central government employees in select African countries between 1960s and 1980s. Country Kenya Number 60,300 Exact Year 1963) Number 42,400 Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 Number (1986) 1 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Malawi Tanzania Uganda Zambia Ghana Somalia 10,745 89,745 62,000 n.a. n.a. n.a. (1964) (1961) 50,008 301,000 310,000 110,634 310,000 56,500 (1987) (1989) (1989) (1989) (1987) (1990) For most years, generally until mid-1970s while rapidly rising, the governments were also raising average real pay for the employees. In there, the governments sought to achieve to objectives. One to redress for the discriminatory pay levels for the natives under the colonial administration, and thereby meet some of the political and economic aspirations of the emerging local elite. Two, to exercise “wage leadership” as a dominant employer, in order to pressurise private employers to follow and dissuade them from a low-wage exploitative tendency1. With both numbers and real average pay on the rise, the public service wage bill share of public expenditures was also in the rise. By early 1980s, Africa’s governments were generally leading those in other regions in terms of relative size of government employment in the economy (see Table 2) and the relative size of the government wage bill (see Table 3). This trend was reflected in the select countries. Table 2: Relative size of government employment (as percent of nonagricultural employment) by World economic and regional groupings. Economic Group and Region Developing Countries Africa Latin America Asia Total Sample OECD Counties Percentage of Central Government Employment Table 3: Relative level of government wage bill (as percent of total wages in the economy) by world economic and regional groupings. Economic Group and Region Percentage of Central Government Wage Bill 30.8 20.7 13.9 23.4 Developing Countries Africa Latin America Asia Total Sample 22.6 14.7 17.2 19.8 8.7 OECD Countries 8.7 Source: Heller P. & Tait A. (1983) Government employment pay, Finance & and Development, Rising and personnel costs declining IMF/World Bank Source: Heller P. & Tait A. (1983) Government employment and pay, Finance & Development, IMF/World compensation Bank While government in the selected countries continued to expand until the early 1990s (see Table 3), the fiscal crisis and high rates of inflation since mid-1970s constrained wage bills at levels below what was needed to maintain the real average pay levels for the civil servants. The severity of the fiscal crisis also had governments reducing budgetary allocations to discretionary operational and maintenance (O&M) expenditures needed to ensure the availability of necessary to complement personnel in delivery of services. Consequently, in the select countries, was as indeed the case in most non-mineral exporting developing 1 Lindauer D.L. & Numberg B., Rehabilitating Government: Pay and Employment Reform in Africa, The World Bank, 1994 Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 2 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs countries the trend evolved in until recently that: government employment was expanding and the total wage bill was on the rise; but at the same time the average real pay of the civil servants was on the decline, the salary structure was being decompressed and fewer complementary O&M) resources were available to enable the employees to perform. This trend significantly contributed to the decline in the morale, discipline and productivity of government employees which took hold in the 1980s. Yet, with the persistence of the fiscal crises, the need to control the wage bill (personnel) costs remains a key policy objective in these countries. Table 3: Expansion in total government employment (including teachers) in the select countries between late 1980s and early 1990s. Country Employment in late 1980s Employment High-Point in 1990s Year Number Year Number Kenya Tanzania Uganda Zambia 1986 1988 1987 1989 424,000 301,000 310,000 110,634 1993 1992 1990 1997 477,233 355,000 320,000 139,000 Personnel numbers are falling but wage bills are rising In the 1990s, government personnel numbers are on the decline in all the four select countries. Uganda has had by far the largest drop in numbers; from 320,000 in 1990 to about 160,000 today. It is noteworthy that Uganda has achieved this by radically restructuring and downsizing the government establishment. This has involved rationalisation of roles, functions, structures through a redefinition of the role of government accompanied by hiringoff, privatisation, contracting out and decentralising to autonomous agencies and local government, and pursuit of operational efficiencies. Tanzania is well on a similar but gradualist trend. Kenya and Zambia have adopted the same policy objectives, but the implementation of comprehensive restructuring and downsizing programmes are not yet firmly in place. Nonetheless, indications are that personnel numbers in these countries are also falling significantly. Table 4: Reductions in Government Personnel Numbers in the Select Countries in the 1990s. Country Highest Employment Level in 1990s Number Year Lowest (1988) Employment Level Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 3 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Kenya Tanzania Uganda Zambia 477,233 355,000 320,000 139,000 1993 1992 1990 1997 459,000 268,000 160,000 125,000 These reductions in numbers however do not translate to a fall in total personnel costs. This situation is best explified in Uganda. Despite the hefty fall in personnel numbers, from 320,00 in 1990 to 160,000 in 1998, the total wage bill has been raised in both absolute and relative terms over the years. The annual wage bill increase has been an average of 36 percent between FY 1993/94 and FY 1996/97. The wage bill share of total government expenditure increased from 15 percent in FY 1992/993 to 37 percent in FY 1996/97 (see Table 5). This is an indication that enhancing the pay for civil servants to living wage levels requires a much higher increase in the total wage bills. Table 5: Uganda Government Employment Wage Bill Trends, 1993-1997 VARIABLE Total Employees Wage Bill: Amount (billion) % Change % Recurrent Expenditure 1992/93 214,000 1993/94 177,000 1994/95 150,000 1995/96 150,000 1996/97 148,000 65 89 125 160 220 - 37% 40% 28% 38% 15% 20% 31% 34% 37% Source: Okutho G. (1998), Public Source Reform in Africa: The Experience of Uganda, A paper presented at the Eastern and Southern Africa Consultative Workshop on Civil Service Reform, Arusha, Tanzania. Africa Countries have comparatively the lowest Government employee per capita Even as the Government of select and other Africa countries strive to downsize, statistics available suggest that the region has comparatively the lowest ratio of Government employment to population (see Table 6). It is noteworthy that OECD countries have an average the highest ratio in General Government (7.7. percent) except in the area of teaching and health where the countries of Eastern Europe and former USSR lead (with 5.1 percent). In these two ratios, Africa is far at 2.0 percent and 0.8 percent respectively. These statistics indicate that economic growth and development in Africa will give rise to relatively higher levels of Government employment especially in the provisions of basic social services. Table 6: Government employment, as percent of population by World regions in early 1990s Regions No of Countries General Government Government Administration Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 Teaching & Health 4 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Africa Asia Eastern Europe & former USSR Latin America & Caribbean Middle East & North Africa OECD Overall Surveyed 20 11 17 2.0 2.6 6.9 Central 0.9 0.9 1.0 Local 0.3 0.7 0.8 0.8 1.0 5.1 9 8 21 86 3.0 3.9 7.7 4.7 1.2 1.4 1.8 1.2 0.7 0.9 2.5 1.1 1.1 1.6 3.4 2.4 Source: Schiavo-Campo S. et al, (1998), Government Employment and Pay: A Global and Regional Perspective, The World Bank. Significance of collapse of systems of control management and management Uncontrolled growth, volatility and weak management of Government personnel/costs are underpinned by collapse of the systems of control and management. These systems are associated with the following problems: Poor personnel data and management information: The most pervasive problem in control and management of personnel the select countries has been the break-down in the systems for collecting, storing and disseminating data on government employees. Information available on Government employment has been generally incomplete and unreliable. This break-down in the systems has availed the opportunities for frauds in the payroll, such as the entry of ghosts workers. The prominent features of the crisis in personnel data and management information are: (a) (b) (c) (d) poor maintenance of personnel records; fragmented and local payrolls; control gaps in the central payroll; and shortcomings in the central personnel data base; and professionalism of a career civil service abandoned service: The select countries, which at independence inherited a British administration model. Historically, employment in the government was structured so that there was clearly a professional cadre of permanent and pensionable officers, (career civil servants) as contrasted with the non-pensionable cadre of support staff. The permanent and pensionable status in government employment was reserved for a relatively small and stable cadre, entry into the cadre was controlled, and the offices were declared by the Head of State. The beginning of loss of control of employment and professionalism in the civil service generally coincides with the abandonment of the dichotomy between the career civil service cadre of permanent and pensionable employees, and the support services cadre; Ambiguous and fragmented institutional framework; Overall the past two decades, there has been progressive erosion of the authority of the traditional institutional pillars of functional responsibility for the exercise of control in the personnel management functions in the select countries. The responsibilities for personnel control and management are scattered Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 5 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs without clear demarcations of functions or authority levels among a relatively large number of institutions; Indiscipline in the civil service: The one personnel control and management aspect which has very much underlined the inefficiencies, misconduct and malpractices in the civil service is the breakdown in discipline. The breakdown has been attributed to: (a) the politicisation of the service under the single party regimes that ruled in the 1970s and 1980s; (b) weak and ambiguous exercise of authority by responsible government officers; (c) breakdown of the complimentary systems of personnel records and performance reporting; lack of transparency in the promotion practices as merit principles were abandoned. Not-so-successful initiatives Governments in the region have attempted all sorts measures to control the size and costs of personnel. In brief, such measures have included: Census and headcount activities: Most census and headcount in the region, geared to identify “ghost employees” form government payrolls initiatives have not been successful.2 This experience is not confined to the select countries. For example, between 1986 and 1988 Ghana carried out census or “headcounts” of civil servants. which did not yield expected results. The census numbers could not be reconciled with existing payroll. In 1988, Tanzania carried out a census of civil servants for which data was not processed until 1991, by which time it was difficult to ascertain the results. A similar excise in 1994 did not fair better; Cash payments to control ghosts: All the governments in the select countries have at some stage in recent years attempted to suspend bankbased payroll payments and adopt cash payment with the aim of identifying “ghost employees”. However, in every instance, this approach has failed because it was difficult to organise and administrate it effectively. In a number of occasions the cash was in fact lost. Furthermore, with cash payments, cases of fraud with scattered payroll, increase; Early retirement of employees: Recently there was a proposal in Kenya, for example, to lower the mandatory retirement age from 55 to 50 years and allow voluntary early retirement of those who are 45 years. However, lowering the retirement age will reduce the numbers, but then raise the costs of retirement benefits. It was therefore proposed to defer pension “Ghost employees” refers to presence of names Government payroll when such employees either do not exist or should already have been removed from the payroll. 2 Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 6 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs benefits for the early retirees until they attain the age of 55 years 3. This was found to be totally unacceptable to these retirees, especially with the thought of the prospect of dying before enjoyment of the benefits. It was also found that the impact of this on the quality of the service would need to be carefully considered. The scheme has therefore aborted. Centrally imposed ministerial personnel expenditure cuts: Directives of such cuts can be on the bias of either an overall ministerial wage bill ceiling, or mandatory targets of personnel expenditure (PE) to operational and maintenance (O&M) expenditure ratio. The Kenya CSRP undertook PE/O&M ratio studies with a view to imposing a 60:40 ratio for ministries. Implementation of these was however not feasible because with the weak personal and public expenditure systems ministries had all sorts of excuses for failure to comply; Reducing the total wage bill: Macroeconomic analysis of the total government wage bill in the select countries yield the conclusion that it is necessary and feasible to reduce the total government wage bill by restraining or curtailing employment numbers. Under one such scenario, the Government of Republic of Zambia was in 1997 persuaded to commit itself to reduce the total wage bill from Kwach 215 billion in June 1997, to Kwach 180 billion in 2002. This goal was to be achieved by reducing the size of the civil service from 139,000 in 1997 to 80,000 by 2002 since then, this policy has been abandoned because it was simplistic and not feasible; Freeze of increases in pay levels: Temporary freeze pay levels is an option that governments have in recent years taken for either or both of the following reasons: (i) facilitate attainment of short term wage bill targets, especially when these targets have been agreed as fiscal performance benchmarks in structural adjustment credits (SACs); (ii) to keep low the costs of retrenchment when these are based on the pay levels. The freeze has usually taken two forms. One, freeze on nominal values. Two, a curb on increase in real pay levels, so that pay increases are limited to compensation for inflation. The latter is the most prevalent practice, and indeed was the default policy of most governments in the region. In 1997, the Government of Zambia explicitly adopted a combination of the two approaches. Thus, pay increased would be limited to compensating for inflation for all personnel, until 1988. Thereafter, however, this policy would apply only for lower ranking and and unskilled staff (classified daily employees). Such policies have, however, rarely held. In 1999, the policy collapsed in Zambia when the President ordered for a 100 percent rise in minimum basic pay. Promising good practices yet to be undertaken Republic of Kenya – Office of the President, Directorate of Personnel Management, Civil Service Reform Medium Term Strategy 1998-2001, April 1998. 3 Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 7 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs There are also some promising good practices which have been intimated but, for various reasons, have yet to be implemented in the select countries. Among these are the following two: Budgetary incentives for MDAs that reduce personnel costs: In Tanzania the budget guidelines for FY 1998/99 promised budgetary incentives for MDAs that reduced personnel costs. In Kenya, a Ministry of Finance task force has been working on a scheme by which MDAs will be allowed to shift savings on PE costs within a ceiling to O&M. This practice has however been difficult to implement under the cost budget system in the select countries. Restoration of budgetary controls: At present, the ministries of finance in the select countries control personnel expenditures on a cash budget basis, releasing funds (exchequer issues) only on the basis of the actual staff in post. When budgetary controls on personnel expenditure are restored, funds will be released to ministries on the basis of approved establishment. This will facilitate decentralised management of human resources, and the practice of budgetary incentives outlined above. Part C: Good Practices Overview Good practices in managing and controlling personnel costs revolve around: Controlling the numbers on the government payroll(s); Imposing a resources envelope for compensation of personnel; Enforcing controls to restrict expenditures within the resources envelope; Eliminating expenditure leaks that allow extra-budgetary expenditures on personnel; and Installing improved systems. As a matter of fact, total effectiveness is likely to require a combination of all these facets of good practice. Nevertheless, on the basis of a survey of select countries the following range of distinct “good practices” have been identified: Flushing out ghost employees; Special payroll audits; Recruitment freeze; Slicing away redundant unskilled workers; Abolishing vacant posts Rationalisation of roles, and functions; Application of staffing Norms; Zero-base reconstitution of the establishment; Firm wage bill freeze; Eliminating compensation allowances outside the salary payroll; Strengthening payroll, checks and controls; Developing more complete and reliable personnel data bases; Integrating personnel and payroll systems; and A comprehensive approach to ensure sustainability. Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 8 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Flushing out ghost employees Total elimination of ghost employees from government payrolls is a goal that is yet to be attained in the country’s covered by the survey. However, remarkably successful initiatives in flushing out the ghosts are documented in Kenya , Tanzania and Uganda the flushing out has taken the following approaches; Payroll verification exercises: In these exercises, employers are required to authenticate their parts of the payroll. Through such exercises, in Tanzania 4,600 ghosts were identified in 1996, and a further 1,500 in 1998. Head-counts: A series of head counts were carried out for various ministries in Kenya resulting in deletion of about 6,000 ghost entries in the payroll. A more comprehensive exercise in Uganda resulted in removal of ghosts employees who remembered more than 10 percent of the total payroll in the traditional civil service (see Box 1). Box 1: Removal of “Ghost Workers in Uganda Because of apparent lack of control on the payroll, the Uganda Civil service was riddled with ghosts. Those who left the service, for various reasons, but their names continue featuring on the payroll – and actual salary being drawn. The emergence of “ghost” can be explained by apparent temptation and collusion between the affected officer and the officials responsible for administering the payroll, as a means of supplementing their pay. To collect this situation, government established a Payroll Monitoring Unit (PMU), to verify the entry and exit from the payroll: and the ground rules established by the Ministry of Public Service (MPS) on the consequences for Public Officers if caught in the creation of ghost workers and the computerisation of the payroll, which enabled the ministry to monitor the changes therein. The elimination of ghost workers was been particularly successful in the Teaching Service, when between September and November 1993, the number of teachers came down form 100,400 to 95,389. In October 1996, Government launched another Payroll cleaning exercise – code named “Operation Cleanup” aimed at removing invalid “ghost” payroll records. Up to 2,800 payroll records were deleted as a result. In addition, over 1,600 staff were removed from the payroll following the earlier Police payroll cleaning exercise. Together, this represents the removal of over 10% of the total payroll records in the traditional civil service. Special Payroll Audit Most past exercises to flush out ghost employees from the payroll have not ascertained financial losses resulting from irregular payments of salaries, failure to account for balances in local (cash) payrolls, etc. On the other hand, the routine and limited payroll checks carried out by Government auditors do not have the scope and depth to document irregularities in the Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 9 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs payroll. This explains the existence of ghost workers in Government payrolls in the select countries. It is therefore a good practice to periodically conduct a special payroll audit. An example of this is to be found in Tanzania (see Box 2). Box 2: A Special Payroll Audit in Tanzania In June 1996, at a meeting of inter-departmental consultations on personnel controls and information system, the office of the Controller and Auditor General (CAG) was required to undertake a special payroll audit. The audit was carried out between October 1996 and February 1997. The audit covered the examination of salary payrolls as well as payments of allowances to various cadres of Government employees in 12 select ministries and departments. The objectives were to assess compliance with relevant staff compensation regulations, and ascertaining effectiveness of internal controls for safeguarding public funds. The audit also included verification of accounting for unpaid salaries and allowances. The audit of the systems of the Government Computer Services department in the Treasury was not thorough because the CAG staff had limited skills in this area. The audit documented extensive loss of Government expenditures on personnel in the following ways: Irregular payments of salaries and allowances, including payments made to exemployees; Failure to account for unpaid salaries; Overpayment of salaries; Incorrect manual adjustments on the computer payroll; and Statutory deductions paid to the wrong institutions. The audit also documented weaknesses in the system of personnel expenditures including the following: Employees with more than one check (personal) number on the payroll; Poor maintenance of employees personal records; and Employees paid without requisite budgetary authorisation. Recruitment freeze In this decade, the select countries have resorted to the policy of recruitment freeze to control growth of personnel numbers. Before the introduction of this policy measure, there was guaranteed entry into the government payroll for large numbers of pre-service trainees in all kinds of public training institutions. This policy as been adopted to varying degrees of effectiveness in the select countries(see Table 7). Table 7: Timing, policy specifics and impact of recruitment freeze in the select countries COUNTRY YEAR POLICY SPECIFICS IMPACT REMARKS Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 10 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Kenya 1992 Total freeze except for teachers and replacement OF health workers. High Tanzania 1992 Recruitment restricted to replacements, and professional and technical personnel in essential services (teachers, health workers, police and prisons), and to be approved by Head of the Civil Service. Low 1995 As above, but replacements also subject to approval by the Head of Civil Service. Only scarce professionals (engineers, doctors, etc) to be recruited with specific approval of the Head of the Civil Service. Uganda 1990 1994 Zambia 1995 1997 High Low Old establishment abolished and a High new one to be created. Recruitment restricted to new establishment. One post to be filled for every Low three that fall vacant. Total recruitment freeze High Numbers in civil service have, reduced from 272,000 in 1993 to 216,000 in 1997. Enforcement mechanisms not clarified. Enforcement mechanisms clarified. Compliance not enforced. Compliance achieved with new establishment controls Mechanisms to ensure compliance not effective. More stringency in monitoring compliance with the policy. Slicing away redundant unskilled workers Large scale reductions in personnel numbers have in some instances been realised through implementation of decisions to abolish and slice away the cadre of unskilled workers4. Two examples of this include: In Uganda, on the basis of the government’s decision to abolish the cadre of “group employees”, the numbers in this cadre fell from about 110,000 in 1990 to about 7,000 in 1997; More recently, in 1997 the Government of Zambia decided to decimate the “classified daily employees”, then numbering 24,00. By April 1999 and todate, some 15,545 of them (about 62 percent) have been removed from the payroll. Abolishing vacant posts In governments where the “approved establishment” is the basis for budgeting and release of funds, for personnel an important first step in controlling personnel costs is abolishing all The cadre of unskilled workers is known by different names in different countries: “auxiliaries” in Kenya; “operational service” in Tanzania; “group employees” in Uganda; and “classified daily employees (CDEs)” in Zambia. 4 Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 11 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs vacant posts. Among the select countries this practice has been relevant for Kenya. In 1993 and 1994, a total of 22,734 vacant posts (equivalent to about 10 percent of the total payroll) in the Government’s approved establishment were abolished. A combination of this measure and the recruitment freeze has ensured sustained reduction in total government employment since 1993. Rationalisation of roles and functions The strategy of rationalisation of Government (ministries) roles and functions to downsize and reduce staff numbers has been applied in all the four select countries in the context of civil service reform programmes. The rationalisation process involves categorising roles and functions of a ministry into (i) core-which are to remain in the public sector; (ii) socially critical-which the government must ensure that some agency in the public and/or private sector provide by decentralisation contracting out, etc; (iii) commercial services to be privatised or abandoned. Generally, on the first attempt, the rationalisation (ministerial reviews) have not had the desired results. For example in the reviews carried out in Government of Kenya, between 1995 and 1997 there were 13 percent cases recommending increase in posts, and only 7 percent of the recommendations were for abolition of posts. In Uganda, the initial (1995) exercise in ministerial reviews yielded demands for additional staff (a total of 27,807) that was nearly 40 percent of the total then on the payroll (38,971). The results from the initial rationalisation (organisation and efficiency reviews) efforts in Tanzania and Zambia were also not encouraging. Still in the some ministries of the select countries, there are cases of “good practice” in rationalisation of roles and functions. These have resulted in changes in structures and reduced staffing. This has been particularly the case in ministries of agriculture in all the select countries. Thus, for example, the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operative in Tanzania has reduced its staff numbers from about 19,000 to about 5,000 between 1996 and 1998. The affected personnel have been retrenched or transferred to local governments under the decentralisation programme. Major reductions in personnel numbers have also been effected through rationalisation of roles and functions in Uganda Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Husbandry and Fisheries. In Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Marketing , the rationalisation preceded the application of staffing norms to determine the future reduced personnel establishment. When the exercise was completed, it was decided to reduce staffing from 24,333 to 17,100. Application of Staffing norms Staffing norms provide criteria for determining optimal staffing levels. Their application also guides MDAs in planning, deployment and utilisation of personnel. The use of staffing norms has been widely in use especially to control recruitment and deployment of field personnel in the delivery of basic social services (education, health and agricultural extension). Staffing norms have also been applied to target across-the-board reductions in personnel, especially teachers. For example, there is a 1998 proposal in Kenya to cut the teaching force by a quarter (63,000 out of a total 244,495) by applying a pupil: teacher ratios of 40:1 for primary schools teachers, and 30:1 for secondary schools teachers. On a similar basis, there have been proposals to reduce teachers by about 6000 (5 percent of the total) in Tanzania. Furthermore, through the use of the ratios, areas and institutions that are overstaffed or understaffed are identified and personnel redeployed on that basis. One of the Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 12 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs best illustrative recent exercises in the application of staffing norms was carried out in the Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, and Livestock Development and Marketing (see Box 3). Box 3: Application of Staffing Norms in the Kenya Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development. Following a rationalisation of roles, functions and structures, it was decided in 1997 to arrive at new staff numbers in the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Marketing (MALDM in Kenya through the application of staffing norms. A common approach to use of staffing norms, which is simple, attractive and appears objective is to adopt the staffing pattern of the best practice of organisation’s elsewhere in the world. In this approach for example, it is conventionally accepted that 1:45 teacher-pupil ratio is appropriate for staffing primary schools in the select countries. It was, however, through such an approach that a previous (1993) consultants’ exercise to determine staffing requirements in the Ministry of Livestock Development had recommended a three-fold increase in staff members (from 2013 to 6,392). Furthermore, the 1997 exercise identified two major drawbacks with such an approach in the MALDM in Kenya. Firstly, the agricultural environment, level of development and demand for public services in Kenya could not be replica of any other country. Secondly, no country could objectively claim to have a universal best practice, and there was therefore a high risk of adopting “sub-optimal” norms. Therefore, uniquely Kenyan staffing norms had to be defined for the MALDM. Staffing norms for headquarters, provincial and district administrative and technical management establishment were determined on the basis of assessment of workload as indicated by analysis of functions, activities service levels and the organisational structures at each administrative tier. Staffing norms for technical functions at the district and divisional levels were based on professional assessments of minimum requirements for delivery of services at that level. On this basis, for example, it was decided to have eight subject-matter specialists per district. Staffing norms were also specified for specialist institutions and services, including training institutes, veterinary laboratory services and farmers training centres. Finally, staffing norms were specified for frontline extension workers (FEW) based on FEW: farmers/pastoralist ratios for each three categories of districts; High potential district (1FEW:800 farmers); Medium potential district (1 FEW:400 farmers/pastoralist) and Medium potential district (1 FEW farmers/pastorlists). Low potential district (1 FEW farmers/pastoralist). At the end of this exercise the long term total staffing for requirements for the MALDM were specified to be 17,100. This suggested the need for a net-reduction of 7,233 personnel in the ministry’s establishment: Source: KK Consulting Associates/Republic of Kenya Staffing Norms Analysis in Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Marketing, October 1997 Zero-base reconstitution of the establishment Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 13 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs One of the most effective good practices in managing personnel numbers when the public service is characterised by low skills levels and poor performance is to reconstitute the establishment from a zero-base. Five key steps in this approach include: First, through the rationalisation of roles and functions determine the ideal structure and staffing for the MDA; Second, declare all posts in the new establishment to be vacant; Third, advertise all the posts to be filled through interviews; Fourth, carry out interviews and fill the posts with the best qualified person; and Declare redundant all those not recruited into the new establishment. This approach was adopted in Uganda in 1993. Reorganisation of government reduced ministries from 38 to 21. At the same time, the programme of ministerial reviews had concluded with considerably reduced numbers of established posts in the new ministries. A Board (The Implementation and Monitoring Board, TIMB) constituted of eminent Ugandans from outside the civil service was given the task of interviewing and filling posts in the new establishment. At the end of the exercise, those not selected by the Board, including 17 permanent secretaries, were declared redundant. A similar exercise is currently underway in Zambia. Firm wage bill freeze One potent instrument for control of personnel costs is enforcing a firm freeze on the Government. It is however, not a readily and easily applied instrument. In fact, few countries have tried it. The Tanzania Government’s 1996/97 wage bill freeze and outturn illustrates the problems and difficulties with the exercise of this option. During a May 1996 IMF mission the wage bill was set at Tshs 177 billion. However, when the IMF returned in August 1996, it was increased to Tshs 185 billion as the original numbers were overly optimistic an retrenchment and understated the numbers of the police force and employees of the prison system. The outturn was Tshs 199 billion because the August 1996 figure was still too optimistic on retrenchment and did not include training allowances for the national service. 5 Thereafter, however, a wage bill freeze has been firmly held in Tanzania, resulting in the fall in value of the wage bill in real terms by 6.9 percent and 14.8 percent in FYs 1997/98 and 1998/99 respectively (see Table 6). Table 6: Tanzania Annual Changes in the Government Wage Bill and Employment, GY 1994/95 – FY 1998/99 Fiscal Year Wage Bill Annual % Real Change in (in T shs Change in the Government Billions) Real Wage Bill Employment 1994/95 109.7 1995/96 156.1 12.2% -9.6% 1996/97 199.2 2.9% -1.5% 1997/98 218.8 - 6.9% -3.8% 1998/99 218.0 -14.8% -2.3% Eliminating compensation allowances outside the salary payroll 5 The World Bank, The United Republic of Tanzania: Public Expenditure Review, July 1998. Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 14 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs Compensation allowances outside the salary payroll have previous been a common feature of personnel costs in the select countries. These allowances are awarded and paid ad hoc and without transparency. They can be a substantial proportion of the total personnel costs, although they may not be reflected in the budget wage bill. In Zambia, it has been estimated that such allowances constitute up to 160 percent of the total salary expenditure. Therefore, these allowances can significantly contribute to volatility of total personnel costs on a monthly basis. Tanzania and Uganda have demonstrated “good practice” in this area; In Tanzania, the government consolidated 36 non-salary allowances into the basic salary in FY 1995/96; In FY 1996/97 Uganda also adopted the concept of a consolidated pay package thereby eliminating compensation allowances outside the payroll. Strengthening payroll checks and controls A common good practice in the select countries for improving controls and management of personnel costs has been strengthening payroll checks and controls. The practice has entailed the following range of interventions: Scrutiny of payroll amendments before entry on the payroll: This practice was introduced in Tanzania in 1995. Before then, changes to the payroll were handled between accountants in ministries and data entry clerks a the Government computer departments; Proper documentation of all payroll amendments: The problem checking for ghost in the Government payrolls in the select countries was in many instances hindered by lack of clear evidence on the perpetrators. The introduction of proper documentation of payroll amendments as introduced in Tanzania (1995) is therefore an important internal control measures; Decentralising responsibility for verification and approval of payroll amendments to specific officers in MDAs: In Tanzania this responsibility was in 1997 given to personnel officers and internal audit staff. A similar but further reaching initiative has been under implementation in Zambia since March 1998. Payroll administration has been moved to line ministries, departments and provinces. The objectives include: (a) making controlling (accounting) officers clearly responsible for changes in the payrolls; (b) easing the identification of discrepancies between payroll numbers and the monthly wage bill through returned salaries; (c) enabling both controlling officers and Ministry of Finance staff to carry out variance analyses on the personnel expenditures budget, and take corrective action; and (d) facilitating controlling officers to report objectively on all expenditures budgeted and incurred under their vote; Stabilising effective institutional arrangements: This entails specifying the institutional focal points for enforcing and monitoring compliance with laid down Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 15 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs policies, procedures and controls. In Tanzania, for example, a Management Information Systems Unit and a Payroll Control Unit were introduced at the Civil Service Department in 1995. A Payroll Control Unit was also established at the Ministry of Finance. In Uganda (1995), they found it useful to create one Establishment Control Department for all Government employees, including teachers; In Zambia, the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development has, in 1998, introduced a Revenue & Expenditure Monitoring Unit whose functions include monitoring payroll deviations; and Documenting the existing systems procedures and controls: Documenting the system ensures that details of systems procedures and controls are readily clarified and understood for implementation by all staff required to do so. The documentation also facilitates training on the system. With the documentation it is feasible to establish a mechanism to undertake regular checks on compliance with the personnel and payroll administration procedures and controls. It is for this purpose that a personnel and payroll procedures manual was prepared for the Government of Tanzania in 1997. Developing more complete and reliable personnel databases Effective management and control of personnel costs requires an accurate and comprehensive personnel database. Such a database will provide timely and complete information on all civil servants, and reveal changes in the personnel numbers and costs, including new recruits and those leaving the service. Then, there can be timely analysis and verification of changes in the monthly wage bill. However, experience shows that installing such a database will be a long term undertaking. Still, in Uganda and Tanzania. there are good practices in developing more complete and reliable personnel databases. In Uganda (1994) there was transfer of all local and manual payrolls to a central computerised payroll to facilitate effective monitoring and control of entries in the payroll. It estimated that about 20,000 ghosts in the Uganda teacher’s manual payroll were eliminated by this computerisation and centralised control. In Tanzania, an initiative was initiated in mid-1988 to establish a centralised and computerised personnel data base. Specially defined forms were dispatched to all employees, through their departments and work stations. Full completion departments and transmission back to the civil service. Department was mandatory. Those not complying on it were threatened with withdrawals of salaries. By April 1988, a 99 percent response had been confirmed. And since then the data returns have been processed into a computerised personnel data base. Integrating personnel and payroll systems An integrated personnel and payroll system is has the objective to improve personnel and payroll processing, retrieval and elimination of data redundancy and duplication. The three specific features of such system are: Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 16 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs automating a central personnel data base; linking this data base to the three main personnel control functions, i.e. complement (establishment control), payroll administration and personnel expenditure budget; system facilitates concurrent updating of the personnel data base and the payroll. Such a system as is currently under implementation in Tanzania will provide support for the following: an approved establishment list operated and managed by the central personnel department which ensures that any request for recruitment can only be approved if there is a vacant post and if funding for the post has been approved; an up-to-date staff list which includes all government employees. This facilitates checks to be performed to ensure that staff positions conform to approved posts, MDA by MDA, and staff numbers are held to agreed ceilings as set out through the personnel budgetary process; improved control of amendments and changes to the payroll so they can only be made after verification and authorisation; timely and cost-effective cross-checking of the payroll against the approved establishment list, which ensures that discrepancies are detected and eliminated, and that overall numbers and pay levels are kept within agreed target levels. A comprehensive approach to ensure sustainability To ensure sustainability control and management of personnel costs, a comprehensive approach is needed. Such an approach is long term and will encompass most of the good practices outlined above. This is a lesson of experience we can draw from Uganda. Here, measures to improve control and management of personnel costs started in early 1990s and are still continuing. The wide range of good practices documented there explain the consistent reduction in personnel numbers over the years (see Table 8). Table 8: Changes in total Uganda Government personnel numbers, 1990-1997 Service Group 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 July July July Sept Sept Traditional Civil Service 70,000 40,000 36,000 29,500 29,500 Teachers 120,000 120,000 120,000 100,000 93,526 Police and Prisons 20,000 23,000 23,000 21,000 26,562 Group employees 110,000 86,000 50,000 26,500 21,881 District-based n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 1997 Sept 15,922 92,954 19,255 n.a. 30,737 TOTAL 158,978 320,000 296,000 299.000 177,000 165,863 Select References 1. Brown K., Kiragu K., and Villadsen (June 1995) Uganda Civil Service Reform Case Study, A report to Special Programme for Africa (under assignment from the UK Overseas Development Administration and DANIDA. Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 17 Issue Paper 6: Controlling and Managing Personnel Costs 2. Gemmell, Norma ed. (1993), The Growth of the Public Sector: Theories and International Evidence, Edward Elgar Publishing Company, Hants, England 3. Okutho, George (March 1998), Public Service Reform in Africa; The Experience of Uganda, A paper presented to the Eastern and Southern Africa Consultative workshop on Civil Service Reform (Unpublished) Kampala. 4. Landauer David L. and Numberg Barbara, ed (1994), Rehabilitating Government: Pay and Employment Reform in Africa, World Bank, Washington D.C. 5. Green, Malcolm (July 1997), Public Service Management in Zambia: A Review of the Government’s Public Service Reform Programme, A report under assignment to the World Bank. 6. Republic of Kenya/Office of the President (April 1998), Civil Service Reform: Medium Term Strategy 1998-2001, Directorate of Personnel Management. 7. Schavo-Campo S., de Tommaso G. and Mukherjee A (1998). Government Employment and Pay: A Global and Regional Perspective, The World Bank, Washington D.C. 8. Rugumanu, Severin, ed (1998) Tanzania National Symposium on Civil Service Reform, University of Dar es Salaam Press. Good Practice in Public Expenditure Management, Capetown June 1999 18