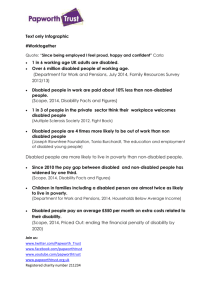

disabled amended

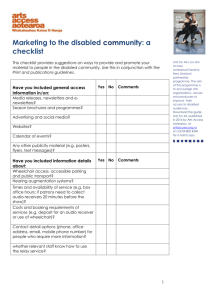

advertisement