What steps have countries taken to curb carbon emissions

advertisement

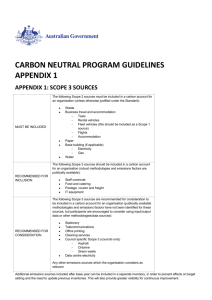

Weather Project: What steps have countries taken to curb carbon emissions? Information: Marina Ratnasingham Poster: Angelie Kennedy Teacher: Mr.Alphonso Class: 2NC 2D Gas Emissions There are several countries that are willing to curb gas emissions. The United States had a meeting with 7 other countries and they agreed that the temperature of the planet should not go up by more than 2 degrees over the pre-industrial levels. As well all the countries agreed to take meaningful steps between now and the midterm maybe 2020, 2025 but to take steps in the midterm to lessen their carbon emissions. Russia, Germany, Italy and Iran are an export driven economy having to do with oil and gases. So for these two countries, especially in the midst of a global economic downturn, to agree to restrict those commercial ties would be a sacrifice. Singapore is a wealthy a global refining and manufacturing country had said that they will do more to lessen its carbon emissions but they say additional steps depend on the shape of a broader pact to fight climate change. Singapore has become a focus for environmentalists who point to the nation's wealth and energy-intensive economy and say the government should adopt emissions targets. Small countries like Singapore or the Bahamas are alternative energy disadvantaged but there was still much the country has done, and could do, to tackle greenhouse gas emissions. Singapore, with power generation capacity of more than 10,000 megawatts, has switched to less polluting natural gas as the main fuel source for electricity, although some larger power stations still use a proportion of dirtier fuel oil. The present annual growth rate in the number of cars on Singapore's congested roads is 3 percent. "We're going to cut that down to 1.5 percent." Top climate change negotiator Chew Tai Soo "We will have a plan to put on the table if there's a global agreement. When there's agreement, Singapore will be part of that agreement," he said. China, the world’s biggest polluter made an elusive deal to fight climate control and invest in clean energy. The proposals, delivered by Hu Jintao, the Chinese president included the promise of a decrease in the carbon intensity of China's economy, the amount of emissions for each unit of economic output, by 2020. Hu said that his country would plant forests across an area the size of Norway, and generate 15% of its energy needs from renewables within a decade. China’s existing Environmental Protection Law, last amended in 1989, sets a maximum penalty of 100,000 yuan ($15,600) on companies that violate regulations, a fee often below the cost of corrective action. China is not the only battleground for the debate on a carbon tax. Expert opinions on whether a cap-and-trade or carbon tax mechanism is the most effective way to reduce carbon diverge widely. While a cap-and-trade policy is effective at limiting the quantity of emissions allowed, a carbon tax is comparatively easier to enforce. A carbon tax “depends on command-and-control regulation,” which, given often weak monitoring capacity in China, would invite polluters “to rig data about carbon emissions when it comes to fee and tax collections.” Among carbon tax advocates, there is little consensus on the optimal tax rate or the price on carbon that can balance the cost of mitigation with the benefits from reducing climate-damaging CO2 emissions. The 2007 UK-published Stern Review, the most comprehensive effort to assign climate change an economic cost, called for a harmonized carbon tax of $350 per ton of carbon (which is equal to $95 per ton of carbon dioxide) in 2015. Many economists have taken issue with this rate, suggesting that one-tenth of that – $35 per ton of carbon or $9.50 per ton of carbon dioxide – is a more appropriate rate. That would translate to roughly $1 tax on each gallon of gas versus 10 cents a gallon. India is ready to calculate the amount of planet-warming gas emissions it could cut with domestic actions to fight climate change, the environment minister said, but will not accept internationally binding targets. India, where about half a billion people do not have access to electricity, said its greenhouse gas emissions could double or more than triple to 7.3 billion tonnes by 2031. But its per-capita emissions would still be below the global average. Deforestation causes between 15% and 20% of the world’s carbon emissions- as much as the whole world wide transport sector. The technology needed to stop this is present- as one panelist put it “we already know how not to cut down a tree” and with satellite imaging, such as that provided by Google Earth Engine, it is now possible to monitor and track deforestation with great accuracy. Therefore stopping deforestation is one of the best tools available to fight climate change. If not worded properly, REDD[ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries] could carry bad encouragement that could actually support deforestation. Without safeguards, companies could receive payments for the adaptation of natural forests into plantations. Forest plantations are not only bad for climate change (they sequester only a fraction of the carbon of a natural forest) but can also carry devastating side effects to the environment. Bibliography: http://www.takepart.com/news/2009/12/17/redd-letter-days-us-announces-1bn-in-funding-to-curbemissions-from-deforestation http://energy.foreignpolicyblogs.com/2009/05/12/china-floats-carbon-tax-plan-as-a-means-to-curbemissions/ http://www.upstreamonline.com/live/article189317.ece http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2009/sep/22/climate-change-china-us-united-nations http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE5871NV20090908 http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/europe/july-dec09/g8_07-09.html