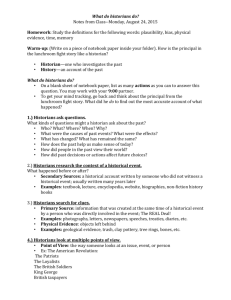

Part I: THE DISCIPLINE OF HISTORY

advertisement