Paper by Jeff Tunks on DNA evidence in criminal cases.

advertisement

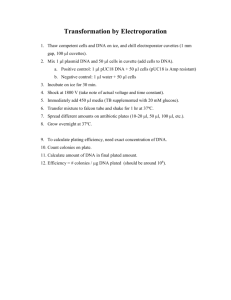

CRIMINAL LAW UPDATE OCTOBER 2011 SEMINAR MARSDENS LAW GROUP CAMPBELLTOWN OFFICE Tel: (02) 4626 5077 Fax: (02) 4626 4826 DX 5107 CAMPBELLTOWN 1957140_1 CSI CAMPBELLTOWN AN INTRODUCTION TO DNA EVIDENCE Jeff Tunks Acc Spec Crim Law. “As we know, there are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns. The ones we don’t know we don’t know. …” Donald Rumsfeld, US Secretary of Defence, Dept. of Defence Briefing, Washington 12 February 2002. The Prosecutor presents you with a Brief of Evidence telling you that your client’s DNA has been found at the crime scene. “How can you possibly run this?” they will say. “I just don’t know”, you may think to yourself. The quotation above is often referred to by Judge Andrew Haesler, one of the leading legal authorities in DNA evidence in Australia. His point is that there is much that we don’t know about DNA evidence. Over the last 20 years, law enforcement has taken advantage in significant developments in the science and technology in the investigation of crime. For many years, fingerprint evidence was regarded by juries as the most reliable independent form of scientific evidence. Although DNA evidence has been utilised in criminal cases in Australia for some time; in recent years the ability and propensity of Police to collect potential DNA samples from crime scenes and obtain analysis has increased dramatically. As a result, there has been a marked increase in prosecutions where DNA evidence is a central part of the Crown case. Over the same period, we have witnessed a flood of television programs (such as CSI, Bones and Law and Order) that have plot lines centred upon forensic cases where the people who solve the case are more often than not the lab technicians and not the Police. These programs (by virtue of the number of them), are very popular and have played a role in the way juries in Australia and other parts of the world perceive DNA evidence. In this paper I propose to briefly examine the following questions: What is DNA? When can the Police take a sample of a person’s DNA? What is the process for extracting DNA and building a profile? Can we challenge DNA evidence? What if the only evidence is DNA evidence? What is the ‘CSI effect’? However, allow me to give the ending to this particular Police procedural drama away here and now. DNA evidence is just a single piece of evidence, to be taken into account with all the other evidence in any case against an accused person. It may well strongly suggest the accused was present at a crime scene but it does not prove that he or she committed the crime. Defence lawyers should not be disheartened or overwhelmed by a DNA statistical profile. The process of collecting and building a profile depends on significant human intervention and human beings are well known for making errors. What is DNA? Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a substance found in all human cells (except red blood cells). There is a body of medical opinion that each and every human being has unique DNA with the possible exception of identical twins. However, it should be remembered that like all science, this is based 1957140_1 2 upon theory rather than irrefutable fact. The reality is, that there is no incontrovertible scientific proof that all humans have unique DNA. DNA evidence can be extracted from the cells of any number of sources from a crime scene including blood, strands of skin, dried sweat, saliva or indeed any other type of fluid or matter that has been in the body that you may care to think of. There need be only a few single cells from which a successful extraction may be taken. Indeed, a nanogram (one thousand millionth of a gram) might be a sufficient amount from which a successful extraction could be made. Once extracted and analysed, a DNA profile is charted using a number of reference points. The usual case will involve a comparison of the crime scene DNA profile to that of a profile from a specific suspect to the crime by way of a buccal (mouth) swab which has also produced a DNA profile. The swab, which looks a little bit like a large cotton bud, is placed in the mouth of the person rubbing the roof of the mouth in a sideways motion for a short time. There is no discomfort. That data between the two profiles is then statistically compared on a database and as a result an analyst from the NSW Division of Analytical Laboratories (DAL), upon finding a sufficient statistical match, will provide expert evidence under s.79 of the Evidence Act 1995 that the suspect/accused has the same DNA profile as the sample recovered from the crime scene. Generally, with the appropriate statistical basis, the expert will give evidence that the matching profile is expected to occur in less than one in ten billion individuals. Very impressive odds, bearing in mind the current acknowledged population of earth is only six billion. Under what circumstances can the Police take a sample of a person’s DNA? The Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Act 2000 provides the process whereby the Police can obtain both non intimate (photographs, fingerprints etc) and intimate (DNA) samples from suspects. Briefly put, all forensic procedures can be carried out with the informed consent of the person1. Informed consent requires the Police provide a caution or warning at the time they are requesting the forensic procedure that they do not have to comply unless they wish to do so and that if they do, any evidence gained may be used in evidence. 2 Children or people suffering from a mental illness are deemed not able to give informed consent.3. This process should be recorded wherever practicable.4 If a person does not consent to providing a sample of their DNA, they can be compelled to do so by a Magistrate5 When considering such application, the Magistrate must decide whether there are reasonable grounds to believe the person is a suspect who has committed a ‘prescribed offence’ (which do not include minor offences such as offensive behaviour) and further, whether there are reasonable grounds to believe the DNA sample might produce evidence that tends to prove (or disprove) that the person has committed the offence.6 In essence, the Magistrate must balance the public interest of obtaining the evidence against interference with the physical integrity as a member of the public. The legislation sets out a number of other considerations such as the seriousness of the alleged offence, the alleged degree of participation by the suspect as well as their age, health and cultural background. The Court will also consider whether there are other ways of obtaining evidence to investigate the offence (other than DNA) that have not been explored and the reason given by the suspect (if any) as to why they did not consent. 1 s.7 s.13 3 s.8 4 s.15 5 s.24 6 s.11 (3) 2 1957140_1 3 The Court may consider hearsay evidence as part of this process. 7 However, it is important to remember that there must be evidence as opposed to the mere assertions or opinion of a Police Officer.8 The law is well settled in regards to how the task should be approached by the Court. In Orban v Bayliss [2004] NSWSC 428, Simpson, J pointed out that the legislation requires a positive finding that the person to be tested is a suspect: “The conditions that must be met, before an order can be made, demonstrate that the purpose of the legislation is not to enable investigating Police (or other authorised persons) to identify a person as a suspect; it is to facilitate the procurement of evidence against a person who already is a suspect” (At [31]). So, there must be some evidentiary basis for seeking the order. The Police cannot simply say ‘I reckon he or she is involved’ on a gut feeling and then seek an order. In granting an order the Magistrate must articulate the evidentiary basis for granting the order. 9 In reviewing the Magistrate’s order, the Supreme Court may consider whether the evidence in question has a proper basis.10 Whilst each application will be considered in its own context, there usually needs to be some DNA material found either on the victim or at the crime scene.11 However, the Police must also show the person was a suspect. In the case of Maguire v Beaton, Police sought to obtain fingerprints from a Mrs Maguire whose son had been arrested in relation to property that had been found in a storage unit. The only thing linking Mrs Maguire to the storage unit was some correspondence addressed to her. She had no prior criminal record and there was no other evidence implicating her in a crime. Latham, J observed: “Mrs Maguire had no criminal record, she was a woman in her late fifties who had been respectably employed for some time and she exhibited no trappings of unexplained wealth. At best there was a suspicion or mere speculation on the part of Police that the Plaintiff had leased the unit. A Police Officer’s assertion of suspicion in the affidavit grounding the application was not enough nor was a suspicion that the Plaintiff may have leased the unit.” The legislation does not provide for the crime fiction scenario of Police or an alleged victim scheming outside the legislative framework to collect a person’s DNA by trick. Nor does it provide for a situation whereby the suspect sample has been picked up from a discarded cigarette butt or coffee cup. 12 Suffice to say, if the Police seek an order to obtain a sample from the suspect and he or she refuses, should the Police obtain a sample without first trying to get a Court Order there would be a strong argument to have that evidence excluded as being obtained improperly under s.138 of the Evidence Act. Similarly, if the Police apply for a Court Order but have not complied with the process set out in the Act, the evidence could also be excluded.13 What is the process? Once the sample has been collected from the crime scene or complainant, it is transported to the Division of Analytical Laboratories for testing. In recent times this has been outsourced on occasion to private labs. As I will discuss later in this paper, it is important to remember that DNA samples collected by Police and then transported for analysis are just like any other exhibit and subject to scrutiny in relation to the chain of continuity. 7 Hardy v Pinazza Unreported SCNSW 18 April 2005, Adams, J Fawcett v Nimmo &Anor (2005) 156 A Crim R 431 9 Maguire v Beaton (2005) 162 A Crim R 21 10 F v Zeiteler [2007] NSWSC 333 11 Walker v Bugden (2005) 155 A Crim R 416 12 See R v Hun SC of Victoria 16 June 2000 13 See R v White [2005] NSWSC 60 8 1957140_1 4 The first step is known as extraction. In order to obtain the best chance for a profile the correct amount of DNA material must be extracted from the source material. The lab will aim to extract 0.5 to 1 nanogram. If the sample extracted is smaller than hoped, it may be subject to amplification. In lay terms, this involves a solution being added to the sample that makes the DNA material more readily identifiable. It does this by producing a number of copies of the DNA. In real terms, this process will also dilute the DNA material so whilst amplification can be done more than once, it will eventually result in the original material ceasing to exist. Once the sample is ready to be analysed it is placed into a device that produces a number of graphs. Each graph has a number of peaks. These peaks are known as alleles. It is those peaks that form the basis for interpreting the sample. In New South Wales, in order for a profile to be considered as evidence there needs to be 10 alleles identified for comparison. One of those alleles will always be an x or y chromosome which identifies the gender of the profile. The crime scene sample is then compared to the sample of the suspect using the analysis graph for each. This process is known as interpretation. If there are a sufficient number of peaks or alleles in each graph to form a match, the information is statistically compared to the profile and opinion …the profile is expected to occur in less than 1 in 10 billion…. The peaks/alleles are referred to by the person conducting the analysis as loci. So, in order to justify any statistical calculation, the samples must share what is known as a 9 loci match. Of course, the 10th loci are the sex chromosome and the most uncontroversial part of the exercise. The statistical program used is based upon a data based utilised in all states of Australia. It is called the Profiler Plus system. Other countries and jurisdictions employ similar systems. Some jurisdictions (such as the US) have much larger population bases to draw from and as such any statistical outcome will be stronger. Quite often, a working file will reveal a partial match. This means that whilst there are some matching alleles, there are less than 10. This will normally result in the process being repeated by further amplification until a result either way can be achieved. Is DNA evidence infallible? When the Prosecution serve evidence of a DNA match they will only provide a certificate from the analyst confirming there is a match and what the statistical component for that match is. In order to consider the strength of the opinion given, Defence lawyers must examine the actual process from the collection of the samples to the opinion being provided. Work done within the lab involves a surprisingly small amount of documentation. The most critical material to be considered is the analyst’s worksheet. This document contains a chronology of each of the processes referred to above, who performed each and when. The results of each process should be recorded. There is, as one might expect, a strict uniform procedure to be followed. Divergence from that may result in inaccuracies to the final result. As mentioned at the outset, whilst established science is not always easy for a lawyer to challenge, human beings and their ability to make errors in using the science is often a starting point to attack. In considering the lab file and working documents, Defence lawyers should ALWAYS check matters including: (a) Has the process for storage and retention been followed in the lab? (b) Has the analyst had their work or findings peer reviewed as necessary? (c) What was it that they actually tested? 1957140_1 5 Say the incriminating DNA is said to have come from a shirt, was it extracted from the front or rear of the garment? If it involved the victim’s blood and the offence was a stabbing, it would be of note if the sample came from the back of the suspect’s shirt as well as whether or not the sleeves of the shirt were also examined. Sadly, again by way of experience in Court, it is the case that for practical (and often appropriate) reasons the technician will only test a very small portion of a garment or towel. Also, as a reality, if they find material, then get a match the lab will stop work. Once there is some evidence to incriminate, the process ceases. (d) Is there a possibility the analyst has been working with multiple exhibits from the same case file at the same time? Has there been the prospect of secondary transfer? Secondary transfer was uncovered in a recent murder trial14 in Wollongong where the accused’s DNA was found on the bra strap of the deceased. They had met and drank together in a hotel on the night of her death. During the trial it became apparent the clothing of the deceased and accused were in very close proximity to each other within the laboratory and indeed examined by the same technician. Following cross examination of the technician in relation to lack of adherence to protocols, the Jury accepted there was a chance of transfer from clothing to clothing in the lab and acquitted the accused. In the murder trial of one Mr Geaseh15 where the accused was charged with murder on the basis of DNA from a cold hit (random match on the Victorian data base), it was found that by co-incidence a sample provided by an unrelated earlier case were examined in the same lab on the same day by the same technician who examined the murder scene exhibits. The only reasonable conclusion was secondary transfer. What would have been a grave miscarriage of justice was averted. How? Well, not because the Prosecution checked for the chance of secondary transfer. Personal and anecdotal experience tells us that as soon as the lab gets a match, the process is stopped and they down tools. In the Marsdens matter of R v B it emerged during a voir dire in relation to the DNA process that the matching material had come from a beach towel and that only the very edge of the second of 64 portions had been tested before the match was made. The process then stopped. The chance of other contributors on that towel (and this was a live issue in the case) was not explored. During the inquest of Corporate Jake Kovco who died following being shot with his own weapon whilst serving in Iraq, there was expert evidence given that DNA can be transferred by the sharing of caps or headwear, via latex gloves, or even a handshake followed by one party touching another surface. For these reasons it is also important that great care is taken to ensure that anything Police collect, store and then transport has continuity. In August last year Marsdens acted in a sexual assault trial where DNA was the major source of evidence against our client. However, upon careful examination the Police admitted to not storing his sample the way they were supposed to (only because they couldn’t be bothered driving further than they had to on the day in question) and not recording (then falsifying) the movement of items to be analysed in their exhibit register. Without wishing to be cruel or uncharitable, my experience is that it is rare not to find some inconsistency in the Police actions. So, if the collection and analysis process is above board, is that the end of your defence? No. Just as with the issue of what is or is not actually tested, the expert certificate will not give any indication as to other ways the statistical material should (or could) be interpreted. The most common example of this is where the suspect has a full sibling (and) or a first cousin of the same gender. When this is brought to the attention of the expert witness they will be forced to admit that the statistical prospects of a match reduce by literally billions. In fact, down to a ratio of thousands. Much better odds for reasonable doubt. This was illustrated recently in the Local Court16 by lawyer, Michael Blair, where the evidence of DNA was the only evidence relied upon by the Police. During cross examination of the expert, Mr Blair illustrated why such evidence should not be blindly accepted. The expert certificate stated: 14 Rv Barnes Supreme Ct of Victoria July-August 2008 16 Police V Le Platrier [2010] NSWLC 22 15 1957140_1 6 “Dion Le Platrier has the same profile (in the Profiler Plus System) as the DNA recovered from a stained area on one of the gloves and from an area on the collar of the jersey. This profile is expected to occur in fewer than 1 in 10 billion individuals in the general population. Dion Le Platrier has the same profile (in the Profiler Plus System) as the partial DNA profile recovered from the handle of the sledgehammer. This profile is expected to occur in approximately 1 in 2.9 billion individuals in the general population.” The expert was cross-examined on the voir dire in relation to this certificate where she explained the process of analysing DNA samples. She was then asked about siblings and the effect they had on the statistical probabilities: “Mr Blair for the Defendant asked Ms Berger whether the statistics would change if the Defendant had a close male relative, and she answered at page 13 of the transcript; A. It would change, yes. Q. You'd agree with me there's no scientific basis at all that DNA of an individual is unique? A. That's correct. Q. The models that the DNA use, as you explained, are only based on databases because naturally enough we haven't DNA tested the whole population yet, have we? A. That's correct. Q. And, in fact, you can't rule out any male sitting in this honourable Court as also being a contributor to the DNA sample found at the crime scene, can you? A. Well, it would be extremely unlikely, but as you say, I cannot rule it out. Q. You can't rule it out, and the reason you can't rule it out is because DNA is an exclusionary process, isn't it? It only excludes people? A. Well, I can-Q. Let me ask that question again. For example, it excludes females. You've been able to exclude all females as the possible source of the suspect sample, haven't you? A. That's right. Q. And as you go through the nine points of your loci, you can exclude people who don't have the same nine points or any one mismatch; that's correct, isn’t it. A. Yes. The Magistrate then asked: Q. So if the person had a male sibling and the person was from a racial minority, then that would mean that the figure of one in ten billion would be one in much, much less than ten billion? A. Much, much less, yes. The Defence then called evidence that the Defendant had 2 full sibling brothers. The expert conducted some additional calculations based upon that new information. Remember, her initial calculations were 1 in 10 billion people. The new statistical chances figures were between 3,513 and 6,252: Q. When you’ve recorded 3,513, one way of interpreting that is that if the brother of the Defendant was DNA tested, there would be a probability of 3,513 that the brother’s profile on the profile ..(not transcribable).. would be the same as the Defendant’s. Isn’t that the case? A. That’s the case, yes - the one in 3,513. Q. Ms Burger, that means that there is a one in 3,513 chance that the brother’s DNA profile matches the crime scene, doesn’t it? A. Yes. Q. The third paragraph down starts with these words: “the profile frequency calculation does not apply to closelyrelated individuals”. You would agree with me that that means that the calculations in relation to the general population do not apply when they are closely related individuals. A. That’s correct. Later in the transcript there are some questions from the Magistrate, where he raises the hypothesis of tossing a coin 12 times and getting heads 12 times. Q. So is this a correct statement or an incorrect statement: That the chances that it’s his brother is about the same as if I tossed a coin twelve times and each time got a head. A. The chances are the same, yes. 1957140_1 7 Q. Madam, the chances of tossing twelve heads in a row - His Honour has just referred to - is exactly the same probability of throwing a head, followed by a tail, followed by a head, followed by a tail, followed by a head, followed by a tail et cetera, et cetera up to 12. A. Yes. Try the coin tossing exercise yourself sometime. Forensic science can be a fickle thing. DNA the only evidence? When the Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Act 2000 (NSW) was introduced the Police Minister, Paul Whelan, was explicit: Hansard, NSW Legislative Assembly, 31 May 2000, p 6293. “It is important to note that DNA will be only one tool in the Police Officer’s kit. They will still need to assemble a brief of evidence against the offender; DNA alone will not convict.” In R v Pantoja, (1996) 88 A Crim R Justice Abadee J at 583 and 584 put it in simple and direct terms. He held that the tribunal of fact must first be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that there is a match between the two profiles. That means only that the Defendant cannot be excluded and therefore it is possible he left the crime scene stain. Further, the matching results could not, in the absence of other evidence, prove beyond reasonable doubt the Defendant was responsible for the crime scene stain. This principle was expanded in R v Karger (2002) 83 SASR 135, where the South Australian Supreme Court held per Doyle CJ at 140-141. “The statistical evidence is undeniably strong evidence pointing to a conclusion that the accused was the source of the incriminating DNA, but is not direct evidence of that fact. And, as is obvious, the statistical evidence must be considered in the light of other evidence in the case.” However, there is no authority to support the contention that DNA evidence alone is sufficient to convict. In his paper DNA in the Local Court – The CSI effect (September 2010), Haesler, DCJ refers to a number of cases where in order to prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt, the Prosecution must point to some other evidence, insufficient of itself to prove guilt, which the DNA evidence alone corroborates (at 9): I have yet to find a superior Court decision where DNA alone has been used to convict: eg where the Crown could not prove the Defendant was in Australia at the relevant time. The case of Forbes comes close. Examples include: R v Gum [2007] SASC 311, where there were similarities in appearance between the accused and the alleged rapist; R v Fitzherbert [2000] QCA 255, where there was evidence of animosity and contact between the accused and the victim; R v Butler [2001] QCA 385 where the evidence was DNA and opportunity and R v Weetra [2004] SASC 337 where the accused lived nearby and stolen property was found near his home. The ‘CSI/White Coat effect’: The public (and it follows potential Jurors) are clearly fans of the increasing number of programs such as CSI and ‘Bones’ where the ernest and diligent forensic officer gets the serial killer within the 1 hour timeslot for the program. In 2007, ‘CSI Miami’ was estimated to have 84 million viewers world wide 17. In these programs, whilst it may take the lead character well into the third series to sort out any unresolved sexual tension with the other main character, the easy stuff, that is solving multiple murders by way of forensic evidence alone, usually gets knocked over well within the hour. 17 Jury Trials and the White Coat Effect – Delahunty 2010 1957140_1 8 In 2010, Jane Goodman-Delahunty and Lindsay Hewson conducted research in relation the response to DNA in criminal cases across over 3,500 Australians. Participants were drawn from a broad range of age, gender, profession and education. Each had to be able to sit on a jury. First, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire in relation to their knowledge of DNA evidence in general. Each participant's scores were ranked and recorded. They were also asked about their expectations and trust in DNA evidence. Next, a cross section of 470 participants were selected to watch an audio visual tutorial that was shown to participants setting out such topics as DNA structure and interpretation. This group was also shown a mock murder trial presentation that depicted a Judge, Prosecutor and Defence lawyer examining witnesses, one being a DNA expert. Half the Jury panels were shown a version where the DNA expert in the trial gave evidence by way of using a multi media presentation. The expert evidence given in the other half of panels was oral testimony only. Following the 470 participants watching the tutorial and trial, they were asked to return a verdict and fill out a further questionnaire regarding how they received the manner of DNA evidence. They were also asked to complete an additional knowledge questionnaire. The results: Overall, pre trial DNA knowledge across all participants was low (24%). The lowest levels of understanding were associated with the highest levels of expectations and trust in the value of DNA evidence. For participants that sat the tutorial, this jumped to 64%. Jurors who had the highest quiz scores were the most sceptical in accepting the DNA evidence in the mock trial. As one might expect, Jurors with the lowest quiz scores were more likely to accept the evidence and convict. As mentioned above, the Jury panels received the expert DNA evidence in two ways. The first by oral evidence alone (as is the case in NSW) with the other half receiving the evidence via multi media presentation from the expert. Jurors who were provided with oral evidence returned an average conviction rate of 80%. However, the conviction rate for Jurors who received the multi media evidence fell to 56%. All very interesting perhaps, but how does that apply to practitioners of criminal law in NSW? Well, Winston Terracini QC often says that 'everyone is a potential Juror .... even Magistrates'.... Defence lawyers should just not sit back and be too afraid to challenge DNA evidence. I understand (more than most) how easy one can look like a fool in cross-examining an expert witness without having any expertise oneself. However, you do not have to be a scientist. If a calm, seemingly independent expert gets into the witness box and ALL the Court hears is something that could be interpreted as 'your client did it on the odds of 10 billion to 1' then any Jury or Magistrate will, in the absence of any other information, convict. Who wouldn't? However, as you can see, things are not always that simple. DNA evidence relies upon what are often 'unknowns'. For example, in 2005 Marsdens appeared in a matter in Batemans Bay on a charge of 'illegal use conveyance.' The Defendant was said to have been driving a car on 16 January 2005 at Batemans Bay. His DNA was found on the steering wheel and gear shift. Open and shut case? Perhaps, except he was in Silverwater Correctional Centre on 16 January 2005. Our client instructed us he had never been to Batemans Bay. 1957140_1 9 In the 2011 matter of P v K represented by Marsdens, the client had been charged on a 'cold match' of DNA left at the scene of a break and enter at a school in 2003. The client could not remember where he was in 2003 and did not recall breaking and entering a school to steal a computer. Yes, his DNA was on a door jam near the point of entry to the school. However, the Prosecution case was that the school had been entered over a long weekend so, even if they prove his DNA was there, how do the Police satisfy the elements that he did the actual breaking in and/or stole anything. There was no evidence as to where his DNA was to where the property was taken from. Conclusion DNA is just another piece of evidence. It does not automatically mean your client is guilty. You do not need to be a scientist to carefully examine the process, both by Police collecting the evidence and in the lab. Think to yourself when confronted with that 1:10 billion expert statement.... “What don't we know about this evidence?” J.J.TUNKS SEPTEMBER 2011 1957140_1 10