Who Wants to Be an Anthropologist?

advertisement

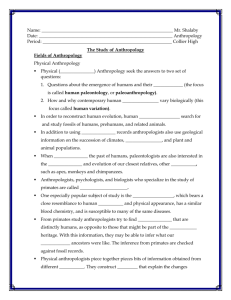

Who Wants to Be an Anthropologist? By: Lee Drummond, Center for Peripheral Studies A Community of Outsiders It is a most curious phenomenon. There exist puzzles, contradictions, paradoxes, enigmas – strange stuff – in our existence that have become so much a part of our lives, of how we see the world, that we do not recognize them as puzzles at all. They have become part of a normal, established order. I believe that one such puzzle is the concept of “community” that cultural anthropologists apply to themselves. This brief essay explores that idea. But what is puzzling about an identity or sense of community that seems perfectly familiar? As comfortable as the bulletproof tweed and worn loafers some of us don before going forth to profess? That identity is puzzling because it embraces a logical fallacy: membership comes through non-membership. I have it on good authority, that is, from an expert native informant: the editor of the Anthropology News once remarked to me in a phone conversation that most of the anthropologists she speaks with describe themselves as “outsiders” – individuals who have gone through life believing that they never really belonged. In high school they were nerds, beatniks, hippies, skanks, all manner of weirdos who were never Student Council presidents or even representatives, never Varsity team football players, never Asquad cheerleaders. They were, in short, pathetic little weenies, what Jim Carrey in Pet Detective hilariously and contortedly describes as l-o-o-o-z-z-z-e-r-r-r-s. Later, in college, in the Peace Corps, or later still, in graduate school, they discovered that their status as perennial misfits seemed to fit them admirably for an involvement with those “others” in the world whom modern society had similarly excluded: tribal peoples; Third World postcolonials; exotic fringe or “subculture” types living in the midst of national societies. They became cultural anthropologists, a community of outsiders. Curiously, this paradoxical membership in a group whose members are excluded from group memberships (one of those self-referential propositions with which logicians torment us) has been embraced as an important element in the ideology or folklore of anthropology. Cultural anthropologists routinely speak of the “culture shock” associated, not only with the initial stage of field work in a distant land, but with the field worker’s subsequent return to his or her “own” society. Having journeyed so far from home, so the sentiment seems to run, there really is never any going back. (Like the crew of the starship Enterprise, the field worker boldly goes where the hand of man has never set foot.) The aliens having become familiar, the folks back home now appear alien. Even so cerebral a savage as Claude Lévi-Strauss (hardly one to indulge in existential angst) writes eloquently in Tristes Tropiques of that sense of déracinément that overtakes the experienced field worker. Never very good ethnographers of themselves, cultural anthropologists generally take their bizarre status for granted, even wearing it as a badge of honor, rather than ask, as any thorough field worker should, how they maintain such a contradictory professional identity. Priding themselves on being hermits and misfits, they are nevertheless committed to acquiring an intimate understanding of their fellow humans, and in particular of exotic humans who are difficult to get to know. It would be quite understandable, and even conform to popular stereotypes, if we were to describe the antisocial natures of theoretical physicists or molecular biologists, for those abstract types are obviously engaged in arcane pursuits having very little to do with the wo/man in the street. They can be neurotic eggheads and perform perfectly well in their chosen field. But cultural anthropologists have a completely different mandate. They are expected not only to survive a great diversity of social encounters, but to understand the inner workings of those encounters better than the average person. Doesn’t this flagrant inconsistency between temperament and task strike you as more than a little strange? Even within the subfields of anthropology, cultural anthropologists have a notably oddball, aloof reputation, whereas archeologists and physical anthropologists are typically thought to be more regular guys and gals, better team players. A few of them probably even made it into student government or onto the football field. As an organizer of international symposia in anthropology once commented to me, “physical anthropologists are very physical, but social anthropologists aren’t even very sociable.” Hmm. (I’m sure there must be a postmodernist trope there somewhere.) Regis to the Rescue With these thoughts rattling around in the back of my mind, it suddenly came to me one Sunday evening while watching America’s favorite game show, “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”: Maybe we’ve been going about it all wrong! The enterprise of cultural anthropology, from Anthro 101 right through graduate seminars in “Hegemonic Modes of Essentialist Narrative Production” systematically selects for the aforementioned nerds, beatniks (well, not anymore), hippies (ditto), and skanks and makes them nerdier and skankier than ever. Hones them to a fine edge of social deviance, does everything but outfit them with black trench coats and automatic weapons, then sends them out to some very remote and difficult neighborhoods to establish rapport and learn things. Isn’t this a recipe for disaster? At least for those of us who like to learn things about the nature of American culture, it struck me like a bolt from the blue, sitting there watching Reg point directly into the camera, directly at you and me, and ask, well, we know what he asks, it struck me that here was a far more effective recruitment and training program for cultural anthropology than all the anthropology courses in all the anthropology departments of our 2 fair land. On the premise (admittedly a contested premise in these postmodern times) that it is possible to know things about a culture, “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” is ingeniously designed to identify individuals who know a lot about American culture. And not just the contestants, those lucky few with the fastest fingers who land on the hot seat, but the stable of writers and editors who labor in the background, assembling, checking, and ordering questions that gauge contestants’ knowledge of this sprawling, brawling land of ours. Departmental admissions committee members, now hear this: Get rid of all those tedious forms, all those deceptive transcripts, all those tortured little autobiographical essays, all those pompous letters of recommendation. And tell the swollen bureaucrats in 3 the swollen bureaucracy at the College Board that they can take a hike, that they can keep their SATs and GREs. That you’ve found something way better: the “Millionaire” Protocol. The nerds and skanks scratching at your door can go back to Nerdville, back to their masturbatory mouse fantasies, back to that vast Skank-o-Rama of dull and unattractive misfits. You’ve found the Real Deal: a simple means of identifying boys and girls, men and women who really know about their culture and who, with a little more education and a lot less mystification, might, in the course of their anthropological studies, come to know a great deal more about their culture and cultures in general. The “Millionaire” Protocol would be a two-part procedure (and so would retain the familiar, comfortable form of the College Board’s “verbal” and “mathematical” tests). Part One would simply involve applicants’ playing the “Millionaire” game, perhaps several times and recording their best scores. Department admissions committees could then screen for the level of performance they required, with community colleges, MooYoos, and the Ivies probably settling into a fairly predictable rank order. (Your guy got a 700 on his Verbal? Forget him! My boy rang the bells at $500,000!) Part Two would be designed to identify the genuinely creative future anthropologist, with applicants being asked to produce lists of “Millionaire” questions and answers of their own, all neatly arranged in the usual order of difficulty. These would be evaluated by experts, ideally by the very staff who compose the questions for the actual show (the trade-off here would be that the professional writers would thereby secure lots of raw material for the show). Applicants with great scores on both parts would comprise an anthropological elite in the making, and would doubtlessly receive offers of full fellowship support from the best schools. Into the Field By now you may be thinking, “Well, this sounds more than a little strange, but it just might work for anthropology programs with strong orientations to American subject matter or, probably more to the point, for actual departments of American Studies. But how would it advance cultural anthropology’s main goal of studying societies all over the world?” My answer: No problem! Fortunately or unfortunately, as those hard-charging avant-garde folks in that “Hegemonic Modes of Essentialist Narrative Production” seminar keep reminding us, we are in the throes (death rattle?) of globalization. “America” is not so much a place as a state of mind, an octopus-like, pervasive, “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” sort of revolting gob of slime that clamps onto the back of the neck of every man, woman, and child alive in the world today, secretes its poison into them and sucks their cerebral marrow. “They” already know an awful lot about American culture, and in fact would probably score higher on the “Millionaire” Protocol than many of the hermity misfits who wind up becoming cultural anthropologists. The real strength of the Protocol, however, is that it can be modified in such a way that it becomes much more than a tool for selecting future anthropologists: it can 4 serve as the principal research strategy for ethnography. Since globalization has already worked its insidious ways, most “peoples” of the world are in fact some offshoot or intersystem of American culture. With that established, we can proceed to construct new “Millionaire” protocols tailored to specific societies or peoples: “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire (Nuer)?”, “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire (Tikopian)?”, and so on. Granted, this is unknown terrain (again, we are going where the hand of man has never set foot) and, like the methodical social scientists we are, it is best to proceed cautiously. In that vein, I would propose a test case: Rather than start right up among the Nuer or Tikopia, select a people who are thoroughly Americanized – remote and exotic enough to be righteous ethnographic subjects, but with a firm historical and social background in American culture. I suggest that an ideal such case is American Samoa (which, for starters, is American Samoa). Its people have been under an American administration for over a century (longer than Arizona has been a state), and have been the recipients of English-language missionary instruction and regulation for a much longer period. With their proficiency in English, daily involvement with an American administration, and round-the-clock immersion in satellite-based American TV (guess what they watch Sunday evenings!), they are ideal subjects for a Protocol that combines the usual questions with a substantial component of questions specifically tailored to Samoan history and experience. With the recent emphasis on auto-ethnography, Samoans themselves would be recruited to produce lists of questions which their fellows would then attempt to answer in wildly popular screenings of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire (American Samoan)?”. Note what is happening here. Besides the great fun of playing and watching the game, the lists of questions and answers assembled over months and years of TV shows constitute an excellent ethnography of American Samoa – perhaps even superior to one a traditional misfit ethnographer could produce. A bonus in choosing American Samoa, of course, is that implementing the Protocol may help to resolve what is cultural anthropology’s most embarrassing and divisive issue: the Margaret Mead - Derek Freeman dispute over Coming of Age in Samoa. Now, with the Protocol in place in American Samoa, an important element of it is the million-dollar question. What will it be? When will the moment come? At last, after weeks or months of watching one contestant after another go into the tank after winning only a crummy $32,000 or $64,000 (pretty much the salary range from assistant to full professor), The Moment is upon us. This new contestant may go all the way! Every flashing light, every bell and whistle on that fantastic Star Wars set is going off. The camera tilts at vertiginous angles, its close-ups showing the contestant, trickles of nervous sweat running down her cheeks (just for fun, we’ll call the contestant Fa’apua’a), then pans to the anxious spouse or mom squirming in the seat behind her. A Samoan version of Reg, bare-chested and wearing pukapuka beads instead of one of 5 Reg’s snazzy silk tie and shirt outfits, launches into The Question. Filled with the gravity of the moment, he asks, “Now tell me, Fa’apua’a, for One Million Dollars (long roll of synthesizer drums), tell me: Are American Samoan girls easy?” Cowabunga! _________________________________________________________ Postscript In something of the way of a self-fulfilling prophecy, my little essay provoked a scathing commentary from one of those not-so-fun-loving anthropologists I described above. Since the critic completely missed the point of the essay, I thought it well to undertake the plodding exercise of explaining it. A good part of my work adopts a humorous approach to deeply serious matters, and few topics are more serious than the one I burlesque here: Margaret Mead’s work on Samoa and the tremendous (and oppressive) effect it has had on the development of modern cultural anthropology. But perhaps I shouldn’t have tried this light-hearted approach to our discipline’s matron saint. As they say, never kid a kidder, and so, perhaps, one should never hoax a hoaxer. Here is my response, from the October 2001 issue of Anthropology Newsletter. ___________________________________________________________ “Who Wants to Be an Anthropologist?” Author’s response to March AN letter to the Editor (“Offensive to Samoans?”) Ms Nardi clearly despises my “swinish nonsense,” although she does not hesitate to root in the trough of invective herself. I’m afraid her self-righteous outrage has caused her to miss the entire point of the essay – which, had she grasped it, would doubtlessly have infuriated her even more. For in one misguided sense, my critic is quite correct: much more is at work (or play) in my little skit than the "just for fun" I admitted to in introducing Fa’apua’a as the American Samoan “Millionaire” contestant. Rather than flippant chauvinism, the closing line – the Million Dollar Question – “Are American Samoan girls easy?” is intended as a stinging parodic criticism of a cultural anthropology that has anointed a shallow thinker (Margaret Mead) and her shallow work (Coming of Age in Samoa) and in the process hobbled the entire discipline at its outset. Lecherous old Franz and the ambitious young Margaret concocted the entire project to pry into the sexuality of the Native Girl, and then, with the help of an eager publisher, flummoxed the entire nation with a bland account of free-and- (yes) easy life in the South Seas.. 6 So my skit is a hoax of Mead’s hoax. But my thoughts in putting it together ran in a deeper and more morbid vein. Mathematicians routinely employ a reductio ab adsurbum argument to demonstrate that a seemingly plausible proposition leads to, or reduces to, nonsense, thus invalidating the proposition. I think any promising theory of culture must adopt a different standard of proof, namely a reduction from absurdity. I would claim that humanity has arisen because, from protocultural beginnings, things did not make sense. Large-brained hominids living in social groups faced continual conflicts in their relationships and their identity. Symbol systems arose, not to name things in a tidy, happy-faced housekeeping operation, but to wrestle with unresolvable contradictions arising directly from interacting and interthinking. Ambivalence is the driving force of culture, not meaning. The Millionaire piece is meant to demonstrate that theory. We begin with an absurd proposal -- to organize research and theory in cultural anthropology around the format of a game show. Yet as we proceed step-by-step, we reach a situation that is all too true-tolife: the closing scene with the Regis surrogate and Fa’apua’a recapitulates Mead's formative contribution to cultural anthropology. We arrive at, or deduce, contemporary cultural anthropology by reducing it from absurdity. If readers find the skit ridiculous or worse, they must indict the whole tradition of American cultural anthropology in the same damning breath. Such is the foundation of sand on which the edifice of anthropology was built. And we wonder why it is in such a mess today. Life, as usual, turns out to be a bad joke. My little parody, obviously too obscure for its meaning to be taken, shares the fate of all bad jokes: it has to be explained. Lee Drummond Center for Peripheral Studies leedrummond@msn.com 7