Introduction and Background

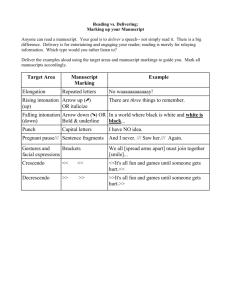

advertisement