Florida Native Plant Society

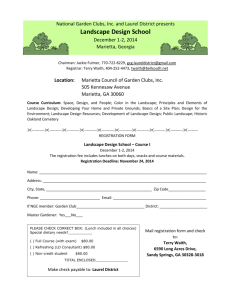

advertisement