Ischemic Colitis: A Clinical Case and Concise Review William K

advertisement

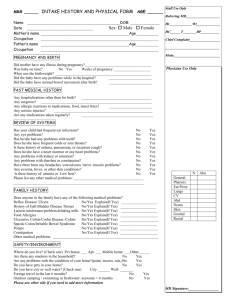

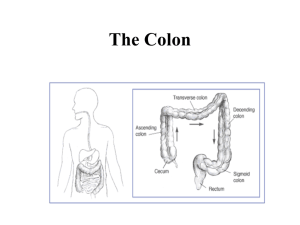

Ischemic Colitis: A Clinical Case and Concise Review William K. Chan, MD Candidate 2013 [1] Nancy Fu, BSc. (Pharm), MD [2] Majid Alsahafi, MD [2] Eric M. Yoshida, MD, MHSc, FRCPC (University of Toronto 8T6) [2] [1] Department of Medicine, University of Toronto [2] Division of Gastroenterology, University of British Columbia Corresponding Author: William K. Chan University of Toronto, Faculty of Medicine 1 King’s College Circle, Toronto, ON M5S 1A8 Email: williamk.chan@utoronto.ca 1 ABSTRACT A previously healthy 64-year-old lady presented with hematochezia, syncope, and abdominal discomfort. Colonoscopy revealed findings consistent with segmental ischemic colitis, which resolved with supportive therapy. Herein we review the case and discuss the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of ischemic colitis. 2 CASE PRESENTATION A 64-year-old lady with hypothyroidism and celiac disease presented with a one week history of malaise and abdominal discomfort. On the day of her admission, she had two syncopal episodes accompanied by hematochezia and melena stools. She denied nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, diarrhea, or weight loss. She had no recent travel or antibiotic and NSAID use. She is an ex-smoker and consumes two glasses of wine four times a week. She had no family history of autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or gastrointestinal malignancy. On examination, she was afebrile. She had an orthostatic drop and left lower quadrant abdominal tenderness Laboratory investigations revealed anemia with a hemoglobin of 117 g/L. She had no previous history of iron-deficiency anemia. Her other bloodwork were normal including complete blood counts, coagulation profile, creatinine and liver enzymes. Although her CRP was elevated at 117 mg/L (normal <3.1), an autoimmune screen including anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), and double-stranded DNA were all negative. Stool cultures and C. difficile toxin were also negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed two days into her admission only demonstrated a small hiatus hernia. Gastric biopsies showed mild inactive chronic gastritis with no evidence of H. pylori infection. Her colonoscopy, however, revealed a 25 cm segment of edematous and friable mucosa with loss of vascular margins at the splenic flexure (Figure 1). There was also significant diverticulosis. Colonic biopsy showed pseudomembranous luminal inflammatory exudate, crypt atrophy, and laminal propria fibrosis suspicious for ischemic versus pseudomembranous colitis. 3 After these procedures, the patient was started on a 7 day course of antibiotics that included ciprofloxacin 500 mg BID and metronidazole 500 mg BID for a diagnosis of acute ischemic colitis. Follow up abdominal and pelvic computed tomographic (CT) scan with IV contrast showed scattered diverticulosis involving the descending and sigmoid colon with no bowel wall thickening or intestinal pneumatosis. Midline arterial vessels enhanced normally with no radiological features of bowel ischemia. 4 DISCUSSION Epidemiology: Ischemic colitis is the most common manifestation of ischemic injury to the lower gastrointestinal tract (1). Although it is commonly seen in the elderly between ages 70-79 years, it can occur in almost any age group. Atypical cases have been reported in young healthy endurance runners who would otherwise have no classical risk factors of hypertension, cerebrocardiovascular disease, or a past history of abdominal surgery (2–4). Women are 1.48 times more likely than men to be affected, and the disease is more common in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (5). Although infrequent at baseline (44 cases per 100,000 person-years), the incidence of ischemic colitis is rising. Moreover, most cases of ischemic colitis likely go undetected because of its short and mild clinical course. Clinical suspicion is often low for this disease as the clinical presentation of ischemic colitis can be very heterogeneous (6). Clinical Presentation: Like our patient, those with ischemic colitis typically present with sudden left lower quadrant pain, diarrhea, and bloody stools. Hematochezia and bleeding per rectum are worrisome complaints in patients with a broad differential diagnosis, and medical trainees from all levels need to properly assess and identify patients at risk for developing ischemic colitis. The disease may manifest across a wide spectrum of injury including reversible colopathy, transient colitis, chronic colitis, stricture, gangrene, and fulminant colitis (1). 5 Although most cases of ischemic colitis resolve quickly, a few situations warrant special attention and consideration for potentially more lethal complications. Isolated right-sided ischemic colitis may reflect super mesenteric arterial disease with an associated mortality rate as high as 50% (6,7). Early identification is crucial especially in elderly patients to prevent complications and to distinguish it from colorectal carcinoma, which can present similarly (8). Both can also occur concurrently as increased intracolonic pressure proximal to a colonic lesion can decrease blood flow and cause ischemia. It is necessary to assess for tissue ischemia because it can affect the integrity of a surgical anastomosis post resection of an obstructing lesion. Pathophysiology: Ischemic colitis can result from modifications in the systemic circulation or anatomic and functional changes to the local mesenteric vasculature. Elderly patients are at higher risk because of multiple co-morbidities and more degenerative changes in the vascular bed. The colon is particularly sensitive to low-flow states because the middle colic and inferior mesenteric arteries create a watershed area that correspond to the splenic flexure (Griffith’s point) and recto-sigmoid (Sudeck’s point) segments of the large bowel (1). The rectum is relatively spared because of its collateral blood supply. Our patient’s ischemic inflammatory changes were in the left colon in the region of the classic watershed areas. Etiology: Of the cases of ischemic colitis that have a specific identifiable cause, most can be separated into the categories of thrombophilia and medications (Table 1). Thrombophilia 6 usually affects younger patients and those with recurrent colonic ischemia. The most common inherited forms are activated protein C (APC) resistance and factor V Leiden deficiency, while the most common acquired disorder is antiphospholipid antibody. Medications that cause ischemic colitis work primarily through mechanisms of vasoconstriction, allergic vasculitis, unmasking underlying thrombophilia, and severe constipation (1). Cocaine is especially concerning among younger patients because it is associated with a higher mortality from septic shock (9). Importantly, infectious agents that include E. coli 0157:H7 and CMV (in immunocompromised patients) can produce a histologic appearance that resembles ischemic colitis although their etiology remains infectious inflammation. Diagnosis: Abdominal CT scan can support clinical suspicion, identify complications of ischemic colitis, and help rule out colon cancer in up to 75% of cases (8). However, definitive diagnosis of ischemic colitis is made by direct visualization of the bowel with biopsies to confirm pathology. Colonoscopy must be performed carefully so as not to overdistend the colon because high intaluminal pressures obstruct intestinal blood flow and can worsen existing ischemic damage (1). Features that suggest ischemic colitis on colonoscopy include a segmental distribution of disease, rectal sparing, and hemorrhagic nodules, which represent bleeding into the mucosa and submucosa. The “colon single-stripe sign” is a single line of erythema with erosions and ulcerations oriented along the longitudinal axis of the colon (10). This finding corresponds to a 75% histopathologic yield and signifies a milder course of disease than does a circumferential ulcer (10). Circumferential ulcers are 7 associated with higher rates of abdominal pain, higher baseline rates of CRP, and longer periods of hospitalization (11). Infarction and ghost cells on pathology are pathognomonic for ischemic colitis (12). Histopathologic findings also give clues about the severity of injury. Mucosal and submucosal hemorrhage and edema with or without partial necrosis and ulceration of the mucosa indicate mild injury (1). Iron-laden macrophages, submucosal fibrosis, and pseudomembranes suggest more severe injury and were present in our patient. Although these findings are also found in C. difficile colitis (13), our patient tested negative for this disease. Ultimately, she may be at risk of developing a stricture because her colonic lamina propria showed early signs of fibrotic replacement. Despite the diagnostic capabilities of colonoscopy, ischemia must be captured at the right time in order for a definitive diagnosis to be made. It is recommended to perform this procedure within 48 hours of symptom onset because the mucosal and submucosal surface can normalize quickly in most cases. When making a diagnosis of ischemic colitis, it is important to rule out other possible diagnoses including infectious colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, diverticular colitis, and colon carcinoma. The work up should include stool cultures, ova, and parasites and C. difficile toxin. C. difficile rarely causes bloody stools, but it should be suspected in hospitalized patients with recent antibiotic use, high total white blood cell counts, and thickening of the colon on CT scan. Increased serum lactate, LDH, elevated white blood cell counts, and metabolic acidosis indicate advanced tissue damage or infarction. Endoscopic features of diverticular colitis range from submucosal hemorrhages 8 (peridiverticular red spots referred to as “Fawaz spots”) to chronic active inflammation resembling inflammatory bowel disease that spares the rectum and terminal ileum. Treatment: In the absence of infarction or perforation, the treatment for ischemic colitis is mainly supportive. Bowel rest and intravenous fluids are standard therapy. Surgery is reserved for those who have failed medical treatment, have persistent symptoms, or have sustained complications (i.e. infarction, hemorrhage, strictures, or fulminant colitis). Intraperitoneal fluid on CT scan, absence of bleeding per rectum suggesting right-sided ischemic colitis, and renal dysfunction indicate more severe disease and are predictive of surgical intervention (14,15). Role of Antibiotics: Antibiotics are thought to protect against bacterial translocation from the loss of mucosal integrity. Some experimental studies demonstrate that they reduce the extent and severity of bowel damage (16,17). However, it is difficult to conduct therapeutic trials because the prognosis of this disease is good in most cases and large patient sample sizes are required to show just a modest effect. Some current guidelines recommend empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics for moderate to severe cases of ischemic colitis. However, a recent systematic review on this issue found a lack of evidence-based trials to support antibiotic treatment (18). 9 Prognosis In over >50% of cases , symptoms of ischemic colitis resolve within 48 hours of conservative measures. However, the colon can take up to two weeks or more to fully heal. Symptoms that persist longer than two weeks are associated with a poor outcome with a higher number of complications and irreversible disease. These patients are immediate candidates for surgical bowel resection. BACK TO THE CASE: Three days into her admission, the patient’s symptoms were resolving and she had no evidence of residual gastrointestinal bleeding. Her hemoglobin returned to baseline (128 g/L) and she was discharged home uneventfully with outpatient gastroenterology follow up. 10 REFERENCES 1. Feuerstadt P, Brandt LJ. Colon ischemia: recent insights and advances. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010 Oct;12(5):383–90. 2. Grames C, Berry-Cabán CS. Ischemic colitis in an endurance runner. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2012;2012:356895. 3. Cubiella Fernández J, Núñez Calvo L, González Vázquez E, García García MJ, Alves Pérez MT, Martínez Silva I, et al. Risk factors associated with the development of ischemic colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep 28;16(36):4564–9. 4. Moses FM. Exercise-associated intestinal ischemia. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2005 Apr;4(2):91–5. 5. Higgins PDR, Davis KJ, Laine L. Systematic review: the epidemiology of ischaemic colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004 Apr 1;19(7):729–38. 6. Montoro MA, Brandt LJ, Santolaria S, Gomollon F, Sánchez Puértolas B, Vera J, et al. Clinical patterns and outcomes of ischaemic colitis: results of the Working Group for the Study of Ischaemic Colitis in Spain (CIE study). Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb;46(2):236–46. 7. Guttormson NL, Bubrick MP. Mortality from ischemic colitis. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1989 Jun;32(6):469–72. 8. Deepak P, Devi R. Ischemic colitis masquerading as colonic tumor: case report with review of literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011 Dec 28;17(48):5324–6. 9. Elramah M, Einstein M, Mori N, Vakil N. High mortality of cocaine-related ischemic colitis: a hybrid cohort/case-control study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012 Jun;75(6):1226–32. 10. Zuckerman GR, Prakash C, Merriman RB, Sawhney MS, DeSchryver-Kecskemeti K, Clouse RE. The colon single-stripe sign and its relationship to ischemic colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003 Sep;98(9):2018–22. 11. Beppu K, Osada T, Nagahara A, Matsumoto K, Shibuya T, Sakamoto N, et al. Relationship between endoscopic findings and clinical severity in ischemic colitis. Intern. Med. 2011;50(20):2263–7. 12. Mitsudo S, Brandt LJ. Pathology of intestinal ischemia. Surg. Clin. North Am. 1992 Feb;72(1):43–63. 13. Dignan CR, Greenson JK. Can ischemic colitis be differentiated from C difficile colitis in biopsy specimens? Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1997 Jun;21(6):706–10. 14. O’Neill S, Yalamarthi S. Systematic review of the management of ischaemic colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2012 Nov;14(11):e751–763. 11 15. Paterno F, McGillicuddy EA, Schuster KM, Longo WE. Ischemic colitis: risk factors for eventual surgery. Am. J. Surg. 2010 Nov;200(5):646–50. 16. Redan JA, Rush BF Jr, Lysz TW, Smith S, Machiedo GW. Organ distribution of gutderived bacteria caused by bowel manipulation or ischemia. Am. J. Surg. 1990 Jan;159(1):85–89; discussion 89–90. 17. Plonka AJ, Schentag JJ, Messinger S, Adelman MH, Francis KL, Williams JS. Effects of enteral and intravenous antimicrobial treatment on survival following intestinal ischemia in rats. J. Surg. Res. 1989 Mar;46(3):216–20. 18. Díaz Nieto R, Varcada M, Ogunbiyi OA, Winslet MC. Systematic review on the treatment of ischaemic colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011 Jul;13(7):744–7. 12 Figure 1: Figure 1A: normal vascular pattern of mucosa (unaffected section) Figure 1B: pale, edematous colonic mucosa with absent vascular pattern and overlying white exudate in a segmental distribution. 13 Figure 1C: complete loss of vascular pattern, friable mucosa as indicated by erythema, edema and granularity 14 Table 1: Causes of Ischemic Colitis Causes of Ischemic Colitis Thrombophilia Medications Mechanical Obstruction Small Vessel Disease Other Inherited: APC resistance, Factor V Leiden deficiency Acquired: antiphospholipid antibody Cocaine Digoxin Pseudoephedrine Amphetamines Sumatriptan Alosetron Colon cancer Fecal impaction Diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia Vasculitis Long-distance running, extreme physical exertion 15