Course HRD 2101: COMMUNICATION SKILLS

advertisement

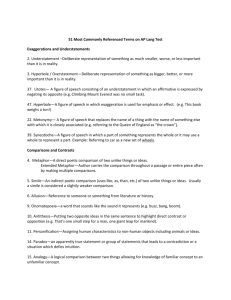

Course HRD 2101: COMMUNICATION SKILLS LECTURE NO. 5 Lecturer: Paul N. Njoroge WRITING SKILLS 1.0 CULTIVATING SKILLS IN WRITTEN COMPOSITION The writing skills you are expected to develop under our Course (Course HRD 2101) are basically English composition skills. English composition simply means generating continuous writing on some subject; composition involves forming words, sentences, paragraphs and pages of passages in order to convey meaning and communication about some subject. The following areas of composition are explicitly spelt out in the Course Description circulated at the outset of our lectures: 1. The Essay. The essay is a composition of moderate length on some particular subject. One could write an essay on subjects like: “The Outreach Programme of the University Farm”; The Michuki Reforms of the Matatu Sector”; “How the Communication Skills Course Has Helped My Studies”; etc 2. Correspondence. This simply refers to letter-writing. You may write personal letters or formal letters, for example an application for a job or for a placement in a professional course. 3. Reports. Reports are compositions written after a request or instructions. Such a request or instructions normally spell out the terms of reference—which areas of a subject you should cover. In that regard, the guided essay you have written for me (“A Description of the Contents and Concerns of My Main University Course to a Lay Person, with a Clear Indication of the Career Prospects Opened out by the Course”) has features of a report. You can also generate a report on the basis of the following instructions: “You are a class representative. Write a report on the views of students from your department on the changes they would like to see made on the contents and scheduling of the Communication Skills course.” 4. Summary. If you are given a written passage of 900 words and asked to summarise its contents into 300 words of the original length, your composition is a summary. Several decades ago this kind of summarising was referred to as précis. Alternatively, you may be asked to write on only one aspect of a larger and more diverse subject. For example, you may be given a passage describing all the subjects taught in the Faculty of Science, and then you are asked to describe the teaching of Mathematics in the Faculty. We will say more about these types of compositions to give you a good idea about how to go about them. And as a bonus we will also tell you how to go about writing a Memo and a Curriculum Vitae or Résumé. You should find this relevant for purposes of making an application for a job. A memo (short for memorandum [plural, memoranda]) is a piece of communication normally circulated to members of the same department for “internal” information. We will also say something about minutes. For our purposes, e-mail is really part of correspondence—in an electronic context. 1 I will repeat what I have said many times during my lectures. You have a responsibility to use your own efforts to improve your communication and, particularly, writing skills. Self-learning should include general reading, paying intense attention to how well-written pieces are put together. Self-learning should also include own writing exercises. I said I would be willing to read your efforts even outside our formal course. I have also made an effort to write my lectures in at least grammatically correct sentences. This should give some guidance. I have also fairly generously quoted good writers; emulate their style. 2.0 ELEMENTARY REQUIREMENTS FOR WRITING UNIVERSITY COMPOSITIONS I have read student essays and while a good number are well presented, there are points of presentation which you should always bear in mind. This is rather an elementary matter but it is of great importance. It is of great importance because the main method of presenting answers to Continuous Assessment Tests and indeed answers to University examinations is through hand-written presentations. So remember: Have a proper heading of the topic, if you are writing an essay. Leave margins at both left-hand and right-hand sides of your sheet of paper. If such margins are not print-ruled ensure 25 mm of margin on the left-hand side and about 10 mm at right-hand side. (Of course the left margin must be hand drawn, while the right side margin will not actually be drawn.) Make sure you write carefully and legibly and, hopefully, in a pleasant handwriting. There are a few students who do not differentiate Capital letters from small letters and this is simply not acceptable. There can be no justification for breaking up words at the end of the line. If a word will not fit, move to the next line. Make sure your paragraphs distinctly stand out, either by indentation at the left hand margin or by leaving a line space between different paragraphs. These are purely technical matters but they are very important. You can endanger your chances for success by writing illegibly. Write rough drafts in a hurry. Then practise rewriting them in presentable legible handwriting. 3.0 THE BASICS OF CORRECT AND EFFECTIVE WRITING We shall talk briefly about each of the types of composition you should have competence in, and how to approach them. But before we do so, we should first be aware of the language skills and knowledge that one should command in order to write good compositions of whatever type and in whichever subject. The following are the language skills that you need to have a good command of: 3.1 A Command of English Grammar The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary defines grammar as “the rules for forming words and combining them into sentences”. James A. W. Hefferman and John E. Lincoln in their very good course book, Writing: A College Handbook (New York/London; W. W. Norton & Company) state: “The grammar of a language is the set of rules by which its sentences are made.” These rules, one should add, are essentially accepted conventions among a language group. A child learns the grammar of their first language or Mother Tongue/Language from listening to the 2 mother and other older people as they speak. A child assimilates the language habits and conventions of her elders. For a second language, the learner may assimilate correct grammatical usage by listening to experienced and knowledgeable users of the language and by reading books written by knowledgeable people. A secondlanguage learner may also consciously study the grammatical rules of the language. It is important to note that the grammar we are speaking about is the grammar of Standard English. Standard English is the type of English used to facilitate communication between English-users from all types of backgrounds—native speakers, second-language users, and so on. It is the language of education and the language of books and published and printed documents. It is the formal language of radio and television broadcasting. To learn how to write the words of an alphabetical language, one learns how the characters of that alphabet are written. To command the grammar of a language—in our case Standard English—one learns how to write a correct sentence, for the sentence is the basic unit of verbal and written communication. We will therefore have something to say about the different types of the English sentence: the simple, the compound and the complex. Develop a command of the construction of these types of sentences—and you will become proficient in writing all types of English compositions. We will also provide a set of exercises to test your command of the grammatical sentence. Attempt these exercises and if you require to carry self-evaluation ask your Class Representative to come to me for the answers. 3.2 Punctuation Punctuation is the technical or mechanical art of putting marks (full stops, commas, question marks, full colons, semi colons, quotation marks, etc) in a piece of writing to indicate the sense in which groups of words are used and should be read in order to get the intended meaning. Punctuation therefore suggests to the reader how the sentences in a written passage should be read. Students should certainly pay attention to correct punctuation. From my reading of students essays, for example, I have become aware that some students do not appreciate the difference between the colon (:) and the semi-colon. So we shall give examples of correct punctuation and some exercises in the use of correct punctuation. 3.3 Spelling Spelling is writing the letters of a word in the correct—and intended—order. I saw recently the reproduction of a report which had appeared in an overseas paper some years back. It was headed: “Businessmen warn over bear-breasted women”, or something to that effect. The word bear does exist and is ‘correct’ but it certainly wasn’t the one intended. Which was the correct spelling of the word intended? Correct spelling is an important feature of good English composition. A learner or a student may need to memorise some spellings. When writing, check your Dictionary to ensure that you are using the correct spelling of the appropriate word. 3.4 Vocabulary and Registers of Language Vocabulary is the body of words known to a person using a certain language—words that may be put to use in a composition. Each person with a certain language 3 competence has his or her “basket of words” into which she dips to construct sentences either in verbal or written communication. One should make sure that one’s basket is as large and full as possible. Attentive reading of good books and good magazine articles as well as listening to good radio programmes, and also making attentive references to dictionaries and Thesaurus will help you to build your vocabulary. One will then be in a position to select the most appropriate sets of words for different purposes and different types of composition. What does the term register mean? There is a good explanation of this term in Frank Smith’s book Writing and the Writer (London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1982). Let us quote in some length (see p. 78): Language takes a multitude of forms; there is no one “best way” of using language, no “correct form” that is appropriate for all occasions. We speak in one way to adults and in another way to children; we speak differently to adults singly and to adults in groups; to friends, strangers, and acquaintances; to colleagues at work and to colleagues over a drink; to professors and to policemen; to our own children, to friends’ children and to children in school; to anyone when we can reasonably request something from them and to anyone when we require a favour. All of these different ways of using language are given a special name by linguists, they are called registers. Some of the differences among registers are attributable to the subject being discussed; you would not talk to a colleague about a picnic the way you would about a death or a shortage in the pension fund. Some differences must be attributed to the relative age, status, and physical and emotional condition of the person you are talking to, together with your perception of what the person knows and would be interested in. … Just as there are many different registers of language as it is spoken, so written language has different registers from speech. … All the different registers of language have become specialized for their particular uses, and written language has developed registers in its own right. Every kind of text has its own rules. Letters are written in different registers from diaries, from company reports, and from business memoranda, newspaper articles, and novels. Letters to aunts are not the same as letters to bankers, even if they are both on the topic of borrowing money. … Lawyers do not write for lawyers the way scientists write for scientists, and both write differently (or should try to write differently) when they write for lay people. Novels for adults are written differently from stories for children, and stories for 12-year-olds are different from those for 8-year-olds. It is clear from this lengthy quotation that register is about more than words used, for it involves the whole question of the style of using language. But the register used also has a lot to do with the kinds of words that are selected from a language user’s or writer’s vocabulary basket. Style covers all areas of the use of language: does the writer use short simple sentences or does she use long complex sentences? This would affect the ‘pace’. Does the writer prefer active or passive verbs? Does the writer prefer concrete words to abstract words? And so forth. In your writing assignments, you should be conscious about choosing the right register for the right audience. This will include style and tone. Being mindful of other people’s feelings, being courteous and avoiding being rude may be seen as an aspect of register. Language experts tell us that register is determined by three factors of communication, namely field, mode and tenor. In this regard Smith refers to 4 Michael Gregory and Susanne Carroll, Language and Situation (London: Routledge, 1978). Field refers to the topic of the communication. Thus technical language and scientific language will be used in the presentation of a technical or scientific topic and the language of narration in a novel. Mode refers to the nature of language: spoken or written, monologue or dialogue, spontaneous or rehearsed. Tenor refers to the relationship of the producer or communicator to the recipient (including aspects of the communicator’s purpose, whether to persuade, excite, teach, and so forth). 3.5 The Use of Idiomatic English Idiom is defined in the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary as “phrase or sentence whose meaning is not clear from the meaning of its individual words and which must be learnt as a whole unit, e.g. give way, a change of heart, be hard put to it. …” And according to Heffernan and Lincoln (Writing: A College Handbook), “An idiom is an expression that cannot be explained by any rule of grammar but that native speakers of a language customarily use. Most English idioms include a preposition that varies according to the words that precede or follow it.” They give the following examples: bored with television tired of television dependent on others independent of others, etc. It should be clear from those examples that to use idiomatic English one needs to have internalised a deep knowledge of the language, as opposed to a knowledge of literal meanings. Look at the following two sentences: 1. He’d planned to severely punish his son, but had a change of heart when his son warmly welcomed him home. 2. A heart transplant means a patient with a diseased heart receives a healthy heart from a donor. In the first sentence, the word heart is used idiomatically; in the second in a literal sense. One can only learn the use of idiomatic English through acquaintance with the use of English by native speakers. Good Dictionaries for users of English as a second language also contain examples of the correct use of idioms. 3.6 Use of Correct Style Style covers a whole range of using language to create a variety of meanings for a variety of contexts, situations, and audiences. Style includes the registers of language employed, the manner of sentence constructions (simple, short, long, complicated, complex) and the kind of words used (abstract, concrete, everyday, technical, specialist, ‘literary’, poetic, etc). The ways of using language become characteristic of individual writers who by the manner of writing manage to project their own personality. It becomes possible from reading a passage from the works of well established authors (e.g. William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, George Elliot, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, John Steinbeck …) to tell by the style who the actual author is. The use of words, the ability to reproduce mannerisms of speech and to portray people’s manners and behaviour and to capture people’s thoughts, emotions and concerns enable authors to create a variety of moods and effects from humour and irony to grave poignancy. 5 Is the author formal or informal or does he or she use colloqualisms, that is, words and phrases belonging to or suitable for ordinary conversation but not to formal speech or writing? For example: “I have a hunch he’s kidding”, meaning “I have the idea that he is deceiving me in a playful kind of way”. “He has pinched my book”, meaning “He has stolen my book”. The style used will, of course, depend on the subject being treated, the audience being addressed, and the purpose of the communication. Some of the factors mentioned in a numbered manner above will be elaborated on before we move to a discussion of actual composition. We shall talk about grammar and the sentence, punctuation and spelling. We shall also say more about registers and style particularly in the context of discussing different types of composition. 4.0 GRAMMAR: THE SENTENCE AS THE BASIC UNIT OF SPOKEN AND WRITTEN LANGUAGE If you can ensure that each sentence in your composition is grammatically correct— that is it obeys all the rules of word order and arrangement—you would have established your mastery of grammar and achieved the major measure of correctness in language use. A sentence may be defined as a group of words which obeys the conventions or rules of correct order and which makes a complete sense. As we have indicated, there are three main forms of sentences—the simple, the compound and the complex sentence. We need to be familiar with these forms of sentences so that we may be able to construct them with ease when we write English compositions. A sentence normally has a subject and a predicate. The subject identifies a place, a person or thing. The predicate tells what the subject does, or is, what it has, or what is done to it. A predicate, therefore, always includes a verb, which may take different forms. Sentences are therefore classified as either simple, compound or complex depending on the number of subjects and predicates they have. As a general rule, a simple sentence has only one subject and one predicate, while compound and complex sentences have more than one subject and more than one predicate. In grammatical terminology, the combination of a subject and a predicate (which, as we have seen, contains a verb) is called a clause. We can therefore say that the simple sentence is a one-clause sentence. A compound sentence has more than one clause linked together using the principle of coordination, while the complex sentence has more than one clause combined through subordination. These two principles will be explained eventually. 4.1 The Simple Sentence In their excellent book, Writing: A College Handbook, the authors, Heffernan and Lincoln, clearly demonstrate what a powerful tool of expression the so-called simple sentence can become in hands skilled in the use of language. There are almost countless things you can do to the simple sentence to achieve an endless variety of expression. The simple sentence can be starkly simple and short. It can also be complexly rich. Look at the following sentences, which are all simple sentences. Notice their great variety. 6 SUBJECT PREDICATE 1. The lion roared. 2. The lion, caught in a hunter’s net roared fiercely, putting a chill of fear in all the animals living in the neighbourhood. 3. The novel about the Mafia was written by an Italian-American. 4. Some medical experts have predicted an escalation of HIV/AIDS related deaths. 5. The path to the observatory is steep. 6. John cried. 7. The stag leapt. 8. Startled and terrified, the stag leapt suddenly from a high rock. The simplest, shortest sentences—The lion roared; John cried—are constructed using a one-word predicate (verb) respectively. In sentence no. 2 the words “caught in a hunter’s net” provide extra information about the subject (‘The Lion’), while the predicate has the verb ‘roared’ modified by the adverb ‘fiercely’ as well as a compound phrase. The words ‘caught in a hunters’ net’ is called a past participle. A participle is a word formed from a verb and used to modify a noun. Bare onesubject, one-predicate sentences can therefore be enriched by using words or phrases that provide more information about the subject and predicate. But the sentence remains simple in form. 4.1.1 Writing the Subject in the Simple Sentence The subject of a simple sentence can be a noun, a noun phrase, a pronoun or a verbal noun. SUBJECT PREDICATE 1. Children (noun) thrive on loving care. 2. They (pronoun) become psychologically distorted through neglect. 3. Studying grammar (verbal noun) requires effort. 4. The price of timber (noun phrase) has risen sharply. But the subject need not appear at the beginning of the sentence: subjects can appear after the verb, as in the following sentences. The noun is printed in bold face. There was a cockroach in the soft drink. It is hard to read small print in insurance contracts. In these examples, the words there and it are only introductory words or expletives and are not part of either the subject or predicate. You can also invert (reverse) the word order and put the subject after the predicate: At the top of the mountain stands the hermit’s hut. 4.1.1.1 Using Modifiers in Subjects A modifier is a word, phrase, or clause that describes limits or qualifies another word or word group. The italicized words modify the subjects in the following sentences. The un-italicized word in the subject group of words is the key subject noun. 7 SUBJECT PREDICATE 1. The price of timber has risen sharply. 2. The strong statement by the president has sent the right signal to armed robbers. 3. A careless waiter poured soup on the carpet. 4. Story books for children are more difficult to write than fiction for adults. 5. Some of the highest acclaimed paintings in history were painted by Renaissance artist Michelangelo. 6. Mohammed Ali, a crafty boxer, has probably remained unmatched in boxing style. 7. Kenyan children influenced by television often assume character roles of actors featured on TV. In sentence no. 1, the word The is an article and the words ‘of timber’ are an adjective phrase qualifying the noun ‘price’. Similar modifications occur in sentences 2, 3, and 4. The word ‘acclaimed’ in sentence 5 is used as a participle—a word formed from a verb and used to modify a noun. In sentence 6 an appositive is used, that is a noun phrase that identifies another noun phrase or pronoun. And in sentence 7 the words ‘influenced by television’ constitute a participle phrase, that is a phrase based on a participle. There are just a few ways in which you can create rich variety in the formation of the subjects of your sentences—even simple sentences. 4.1.2 Writing the Predicate: Using Linking, Intransitive and Transitive Verbs 4.1.2.1 Linking Verbs A linking verb is followed by a word or word group that identifies, classifies, or describes the subject. Is is called ‘the verb to be’ and gives us the most common linking verbs, namely: is, are, was, were. Other linking verbs include: seem, become, feel, sound and taste. The following sentences all have linking verbs, which have been italicized. SUBJECT PREDICATE 1. Kitili Mwenda was the first African Chief Justice of Independent Kenya. 2. Tourism is Kenya’s biggest foreign exchange earner. 3. The Bantu were the earliest settlers in the Lake Victoria region. 4. Susan became sick after drinking unheated water. 5. She feels elated at the prospect of flying to the United States. 6. She seems elated. 7. The Vice Chancellor sounds positive on the prospect of keeping course fees at their present level. 8. The yoghurt tastes just fine. 4.1.2.2 Intransitive Verbs An intransitive verb names an action that has no direct impact on anyone or anything named in the predicate. 8 SUBJECT PREDICATE 1. The rich also cry. 2. The Nile River flows turbulently in the northern summer. 3. The thieves vanished into thin air. 4. The long rains have come. 4.1.2.3 Transitive Verbs A transitive verb names an action that directly affects a person or thing mentioned in the predicate. The word or word group naming this person or thing is called a direct object (DO). SUBJECT PREDICATE Tr. V DO 1. The violent storm destroyed the wheat crop. 2. Violent robbers may kill their victims. 3. HIV/AIDS threatens the very survival of Africa. 4. She wrote a song about the matatu industry. Transitive verbs may either be in the active or the passive voice. A verb is in the active voice when the subject performs the action named by the verb. A verb is in the passive voice when the subject undergoes the action named by the verb. All the above sentences have verbs in the active voice. Sentence no. 1 may be rendered in the passive voice as follows. SUBJECT PREDICATE The young wheat crop was destroyed by the storm. Transitive verbs in the active voice give a piece of writing pace and create a sense of activity. A fast-paced story relies quite a lot on transitive active verbs. This is not the case with the passive voice or even with intransitive verbs. 4.1.3 Achieving Expressiveness Using the Simple Sentence: Things You Can Do With the Simple Sentence James A. W. Heffernan and John E. Lincoln in their excellent book, Writing: A College Handbook (New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company) illustrate a great variety of things you can do with the simple sentence to make it richly expressive. The use of modifiers—a modifier being defined as a “word, phrase, or clause that describes, limits, or qualifies another word or word group—both in the subject and the predicate is one way of making the simple sentence more expressive. We have highlighted modifiers used in the subject; and the examples given above also feature modifiers in the predicate. Let us now point out some of the modifiers in the predicates of sentences given earlier as examples. The modifying words and phrases are italicised. SUBJECT PREDICATE 1. The lion, caught in a hunter’s net roared fiercely, putting a chill of fear in all the animals living in the neighbourhood. 2. Startled and terrified, the stag leapt suddenly from a high rock. 3. A careless waiter poured soup on the carpet. 4. The price of timber has risen sharply. 9 Below we identify different types of modifiers by their grammatical terms. 4.1.3.1 Adjectives and Adjective (Adjectival) Phrases Adjectives modify nouns, specifying such things as how many, what kind and which ones. A wise student reads classical books. The judge, stern and solemn, pronounced the death sentence. Adjectival phrases begin with a preposition—a word like with, under, by, in, of, at. Hostels for women have sprung up all over Parklands. He appears to be in the money, but he is actually in debt. Words which are usually used as nouns can act as adjectives: He was the first person in his village to build a stone house. Then he became the village drunkard and dismantled his house. The judge handed down a death sentence. Timber prices have risen. 4.1.3.2 Using Adverbs and Adverb (Adverbial) Phrases An adverb tells such things as how, when, where, why and for what purpose. Timber prices have risen steeply. He drove dangerously fast. Most adverbs are formed by adding ly to adjectives. He made a quick retreat. (adjective) He retreated quickly. (adverb) He was lucky to arrive on time to receive a free gift. (adjective) He luckily arrived on time to receive a free gift. (adverb) Some adverbs—such as never, soon, and always—are not based on adjectives at all. An adverb phrase begins with a preposition: at, to, with, in, since, from, … In the year 2002, the Kenya African National Union party lost the general elections for the first time since independence. 4.1.3.3 Using Appositives An appositive is a noun or noun phrase that identifies another noun phrase or a pronoun. The Nazis, cynical nihilists, led the German nation to moral ruin and physical destruction. The village roads, veritable quagmires of mud during the rainy season, deter visitors from the town. 4.1.3.4 Using Participles and Participle Phrases to Modify Both Subjects and Words in the Predicate A participle is a word formed from a verb and used to modify a noun; it can enrich any sentence with descriptive detail. A participle phrase is a participle which has been expanded into a phrase. 10 The weeping woman stared at her injured child. Enjoying every minute of the game, the foreward terrorised the defence of the other team throughout the game. You can use a present, past and perfect participle. Barking dogs never bite. (Present) A carved figure was kept in the family shrine as a family god. (Past) Having struck an iceberg, the luxury ship sunk into the cold wintery waters of the Atlantic. (Perfect) PARTICIPLES IN BRIEF Present participle: planning Present participle phrase: planning every minute of the journey Past participle: influenced Past participle phrase: influenced by flattery Perfect participle: having lost Perfect participle phrase: having lost the election 4.1.3.5 Using Infinitives and Infinitive Phrases The infinitive is made by placing to before the bare form of the verb. Infinitive phrases are phrases formed on the basis of infinitives. The sick man was only sustained by the will to live. She was determined to succeed. To write with rhetorical force, you must read books written by good authors. A split infinitive is an infinitive with intervening words between to … and the bare verb. You need to energetically tackle your language problems. Avoid split infinitive: You need to tackle your language problems energetically. 4.1.3.6 Using Compound Phrases According to Heffernan and Lincoln, “compound phrases help to turn short, meagre sentences into longer, meatier ones; a compound phrase joins words or phrases to show addition, contrast or choice. Compound phrases showing addition, contrast and choice The ideas in the five short sentences can all be combined into one meatier simple sentence, to achieve addition: The The The The The path path path path path was was was was was narrow. steep. crooked. slippery. treacherous. COMBINED: The Path was narrow, steep, crooked, slippery and treacherous. 11 To show contrast the ideas in the following two shorter sentences can be combined into one longer sentence: Pulling Africa from the deep pit of underdevelopment is a gargantuan task. But it is not an impossible task. COMBINED: Pulling Africa from the deep pit of underdevelopment is a gargantuan but not an impossible task. To show choice, the two shorter sentences can be combined into a longer sentence. Africa must seize the initiative for her own development. Or she will lay behind the rest of the world forever. COMBINED: Africa must seize the initiative for her own development or lag behind the rest of the world forever. 4.1.3.7 Using Absolute Phrases An absolute phrase usually consists of a noun phrase followed by a participle. The woman wept silently, her tears flowing down her cheeks. Heffernan and Lincoln illustrate you can form compound phrases with absolute phrases and use them in succession as in the following examples: The factory, its freshly painted walls gleaming in the light and dazzling the beholder, symbolized economic progress. The village was silent, its shops closed, the streets deserted. PROBLEMS WITH MODIFIERS 1. MISPLACED MODIFIERS A misplaced modifier is one which does not point clearly to the word or phrase it modifies. (1) I asked her for the time while waiting for the bus to start a conversation. (2) The College Librarian announced that all fines on overdue books will be doubled yesterday. TO CORRECT, put the modifying phrase next—either before or after—to the main word being modified, as follows: (1) While waiting for the bus, I asked her for the time to start a conversation. (2) The College Librarian announced yesterday that all fines on overdue books will be doubled. 2. SQUINTING MODIFIERS A squinting modifier is one placed where it could modify either of two possible headwords. (1) The street vendor she saw on her way to school occasionally sold wild mushrooms. TWO CORRECT VERSIONS POSSIBLE. The street vendor she occasionally saw on her way to school sold wild mushrooms. 12 The street vendor she saw on her way to school sold wild mushrooms occasionally. 3. MISPLACED RESTRICTERS A restricter is a one-word modifier that limits the meaning of another word or a group of words. Restricters include almost, only, merely, nearly, scarcely, simply, even, exactly, just and hardly. Usually a restricter modifies the word or phrase that immediately follows it. What is the difference in meaning between the following three sentences? 1. Only Cheers serves fried chicken on Sundays. 2. Cheers serves only fried chicken on Sundays. 3. Cheers serves fried chicken only on Sundays. Editing Misplaced Modifiers Dangling Modifiers A modifier dangles when its headword or word it is intended to modify is missing— such that the modifier attaches itself to a false headword. WRONG: After doing my homework, the dog was fed. CORRECT: After I did my homework, I fed the dog. After doing my homework, I fed the dog. 4.2 Compound Sentences: Compound Sentences are Formed Using the Principle of Coordination To coordinate two or more parts of a sentence is to give them the same rank and role by making them grammatically alike. Simple sentences are coordinated to make a compound sentence. In the compound sentence, the previous simple sentences are described as clauses. A clause is a group of words that has a subject and predicate. The subject is made of a noun or a pronoun or a noun phrase or a verbal phrase, and there is a verb in the predicate. An independent clause is to all intents and purposes like any simple sentence; it makes a complete sense. (A subordinate clause, which is not used in a compound sentence, has a subject and a predicate, but cannot stand as a complete sentence.) Four ways are used to make a compound sentence using the principle of coordination: 1. Using Conjunctions; 2. Using a Semi-Colon; 3. Using Conjuctive Adverbs; 4. Using Correlatives A. Compounding with Conjunctions The conjunctions are the following words: and, but, for, or, nor, so and yet. 13 1. Compounding to show simple addition The two sets of underlined words constitute the two independent clauses in each sentence. The economists considered budget cuts, and the politicians thought of votes. He thought of achieving great success, and he worked eighteen hours a day in that regard. 2. Compounding to add a negative point He had not achieved any distinctive success by the time he was fifty, nor did he expect to achieve any success for the remainder of his life. 3. Compounding to show contrast Our member of parliament claims to be a man of the people, yet we see him only during election campaigns. 4. Compounding to show logical consequence He welcomed his inlaws warmly to his house, for he wanted to express his high regard for them. 5. Compounding to show choice Jane could enrol in Strathmore University to pursue a CPA course, or she could join Komo Kenyatta University to study Actuarial science. B. Compounding with the Semi-Colon A semicolon alone can join two independent clauses when the relationship between them is obvious. INDEPENDENT CLAUSE ; INDEPENDENT CLAUSE 1. Some books are undeservedly forgotten ; none are undeservedly remembered. (W. H. Auden) 2. Authors do not develop ; independently of the influence of others they benefit from both the example of past authors and contemporary practitioners. C. Compounding with Conjuctive Adverbs 1. Conjuctive adverbs showing addition: besides, furthermore, moreover, in addition 2. Conjuctive adverbs showing likeness likewise, similarly, in the same way 3. Conjective adverbs showing contrast however, nevertheless, still, nonetheless, conversely, instead, in contrast, on the other hand, in spite of 4. Conjuctive adverbs showing cause and effect accordingly, consequently, hence, therefore, as a result, for this reason 14 5. Conjuctive adverbs showing a means-and-end relation thus, thereby, by this means, in this manner. 6. Reinforcement for example, for instance, in fact, in particular, indeed 7. Conjective adverbs of time meanwhile, then, subsequently, afterward, earlier, later EXAMPLES OF SENTENCES USING TYPES OF CONJUCTIVE ADVERBS MENTIONED ABOVE 1. African countries require the cancellation of debts; in addition, they need fair terms of internal trade in order to make any headway. (ADDITION) 2. To learn how to read one has to memorise all the 26 letters in the Latin alphabet; similarly, to learn to use the major music scale, one has to know the eight notes in the tonic solfa. (LIKENESS) 3. To become a successful parent, one needs to have sufficient money; however, a parent cannot become successful without a sense of caring. (CONTRAST) 4. Public universities were only able to admit a fifth of successful candidates; as a result, a vast majority of successful candidates became desperate job seekers. (CAUSE AND EFFECT) 5. Jaramogi Oginga Odinga not only left the government in 1966 to form an opposition party but also demanded a multiparty system during the authoritarian years of one party rule; therefore, he is remembered as the champion for multiparty democracy in Kenya. (A MEANS-AND-END RELATION) 6. Most of the economic indicators show Africa to be deplorably underdeveloped; for example, the average per capita income for sub-Saharan African countries is less than US $ 400. (REINFORCEMENT) 7. In the meanwhile Africa can content itself with forming regional trading blocs; later, it will have to seek continental union. (TIME) Need to Avoid the Mistake of Comma Splices or the Comma Fault The mistake of joining two independent clauses (that is two possible sentences) with nothing but a comma should be avoided. Correct the mistake by putting a conjunction (and, but …) after the comma. For example: WRONG: The attack of the enemy was rolled back, our army soon turned the enemy’s retreat into a rout. CORRECT: The attack of the enemy was rolled back, and our army soon turned the enemy’s retreat into a rout. D. Using Correlatives Correlatives are words phrases used in pairs like both … and, not only … but also, either … or, neither … nor, and whether … or. These correlatives are used to join two or more independent clauses expressing what is called parallel ideas. The following sentences provide examples of how to use correlatives. 1. His brutality not only horrified the opposition, but also it alienated his erstwhile supporters. 15 2. A student should either be prepared to do her own interest-driven self-reading for success in literature, or she should not study literature at all. 3. Whether you decide to marry or you decide to live single, you will regret it. 4.3 Complex Sentences 4.3.1 The Principle of Subordination Complex sentences are formed by combining clauses using the principle of subordination. Unlike the use of coordination whereby two or more independent clauses having the same rank and weight are combined, subordination make one or more clause depend on the clause of the sentence which is considered most important. The clause that is considered most important becomes the independent clause, while other clauses ‘hang’ on the independent clause as dependent clauses. An independent clause can in separation have the grammatical status of a simple sentence; a dependent clause cannot in separation stand as a sentence. The principle of subordination is used for purposes of the writer emphasising the most important idea by putting it in the independent clause, while the less important ideas are placed in the dependent clauses. Look at the following pairs of sentences, with the independent clause in bold face and the dependent clauses in italics. 1. After he had conferred with his lawyer, the prisoner entered a plea of ‘not guilty’. The prisoner conferred with his lawyer, before entering a plea of ‘not guilty’. 2. (From Heffernan/Lincoln:) Amelia Earhart, who set new speed records for long-distance flying in the 1930s, disappeared in 1937 during a round-the-world trip. Amelia Earhart, who disappeared in 1937 during a round-the-world trip, set new speed records for long-distance flying in the 1930s. In the Pair of sentences in no. 1, there are two different emphases: the first sentence emphasises the idea that the prisoner entered a plea of not guilty, while the second sentence emphasises the idea that the prisoner conferred with his lawyer. In the pair of sentences in 2, Amelia Earhart’s disappearance is highlighted by inclusion in the main clause in the first sentence; while her setting of new speed records is the main idea in the second sentence. Other Examples of Complex Sentences SUBORDINATE CLAUSE INDEPENDENT CLAUSE 1. Before the V.C. spoke on graduation day, he studied his notes. INDEPENDENT CLAUSE SUBORDINATE CLAUSE 2. Medical researchers have long been seeking a cure for AIDS which takes millions of lives each year. INDEPENDENT CLAUSE SUBORDINATE CLAUSE SUBORDINATE CLAUSE 3. The president was cheered as he finished his public address in which he promised massive tax cuts. 16 4.3.2 Subordination Using Adjective (Adjectival) or Relative Clauses Look at the following sentence: The horse that won the race was probably led into the stables by the jockey. The independent clause is in bold face, while the dependent clause is in italics. The word that in the dependent clause is called a relative pronoun. The relative pronoun refers to the noun horse which is grammatically called an antecedent. This kind of clause beginning with a relative pronoun—the other pronouns are which, that, who, whom, or whose—is called an adjective (adjectival) clause or a relative clause. An adjective clause modifies the antecedent. Examples of sentences using Adjective Clauses 1. A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. (Oscar Wilde) 2. Jomo Kenyatta, whom everybody remembers as a foremost African nationalist and statesman, was the author of a foremost anthropological study, Facing Mount Kenya. 3. A mind that is stretched to a new idea never returns to its original dimensions. (Oliver Wendell Holmes) 4. Shakespeare’s tragic plays, which he wrote at the height of his dramatic genius, probe the depths of human suffering. 4.3.2.1 Restrictive and Non-Restrictive Adjective Clauses Non-restrictive adjective clauses provide extra information on the antecedent, without defining the antecedent, which is otherwise clearly defined. In the following sentence, for example, the antecedent is clearly defined, being the proper name of a person. The adjective clause in this non-restrictive use is set out between a pair of commas. Jomo Kenyatta, whom everybody remembers as a foremost African nationalist and statesman, was the author of a foremost anthropological study, Facing Mount Kenya. (non-restrictive adjective clause) Contrast this sentence with the following: Students who score an average B grade will be eligible for admission in public universities. (restrictive adjective clause) Here the adjective clause gives definition to the antecedent—students—who are eligible for admission. There are no commas setting off this adjective clause, as there are for setting off non-restrictive clauses. 4.3.3 Using Adverb Clauses An adverb clause begins with a subordinator—a word like when, because, if and although that introduces the subordinate adverbial clause. Other subordinator words or phrases are: until, after, as soon as, as long as, before, ever since, as, while. Whereas, while, so that, so … that, whatever, wherever, whoever, whichever, however. An adverb clause modifies a word, phrase or clause. It tells such things as why, when, how, and under what conditions. Examples of sentences with adverb clauses are given below, with an indication of the role the adverb clause plays in the sentence. 17 1. Showing Time The University closed when the end-of-semester examinations were completed. Until all the voters had had their votes, the election station remained open. 2. Showing Causality Since the saw mill had run out of timber, it closed down. The guerrilla leader was in despair because he had lost three quarters of his fighters in the battle. 3. Concession and Contrast Being employed cannot make you wealthy, although it can make your life reasonably comfortable. Although the weather outside was outrageous, we had a jolly good time inside the wood-fire heated main bar of restaurant. 4. Condition If oil deposits were discovered in Kenya, the country would quickly become wealthy. 5. Purpose He busied himself with the papers on his office desk so that he could impress the supervisor who was on a tour of inspection. 6. Place Your car keys may probably be found where you lost your purse. 7. Result He dug the earth deeply so that the crop planted would thrive. 8. Expressing Range of Possibilities Whatever budget proposals are favoured by the politicians, the business community will want their views considered. 9. Comparison Some African countries are poorer forty years after independence than they were in independence. 4.3.3.1 Punctuating Adverb Clauses Adverb clauses at the beginning of the sentence are followed by a comma. Even though he applied himself to exam preparation, his performance was average. An adverb clause coming at the end of the sentence is not preceded by a comma: The football fans poured into the stadium when the stadium gates were opened. 4.3.4 Using Noun Clauses A noun clause is a clause used as a noun within a sentence. 18 1. A noun clause can be used as subject. What Amin did shocked Africa and the world. Whoever earns a distinction will get a full scholarship. 2. A noun clause may be used as object The insurgents will fight with whatever they have. No one knew what the fuss was all about. 3. Using noun clause as predicate noun The greatest mystery is why she married the eighty-year old man. The main reason for setting up the factory is that it will benefit the community. 4.4 Coordination and Subordination Sentences are not always purely simple, compound or complex. It is possible to have a sentence that combines the principles of coordination and subordination so that it has, say, two main or independent clauses and, say, one subordinate clause. So the sentence is both compound and complex. Let us cite an example from Heffernan/Lincoln: No one had the guts to raise a riot, but if a European woman went through the bazaars alone somebody would probably spit betel juice over her dress. (George Orwell) The two main clauses in this sentence are: 1. No one had the guts to raise a riot. 2. Somebody would spit betel juice over her dress. The subordinate clause is: ‘… but if a European woman went through the bazaars alone …’ Another example, with main/independent clauses in bold face and the subordinate clause in italics: While Africa is richly endowed with natural resources, it is not so well endowed with human resources: its general population has not benefited from mass education, and its political managers are short-sighted. 4.5 Conclusion Grammar—the rules of correctly forming sentences—is probably the most important factor in writing English compositions. We have provided a good number of examples of how to write correct sentences and how to achieve good expressiveness in the sentences that we write. The sentence is the building block of any composition. The student is advised to pay a lot of attention to the kind of sentences she or he writes. But our basic advice remains: the best way of acquiring good grammatical skills is to read books written by good writers and to listen to skilful speakers of English, and especially radio announcers on reputable broadcasting services. The focus in the next Lecture is on actual writing of different types of compositions. 19