Abstract

advertisement

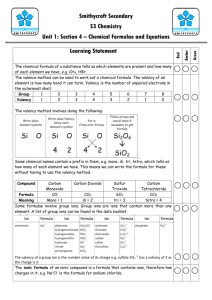

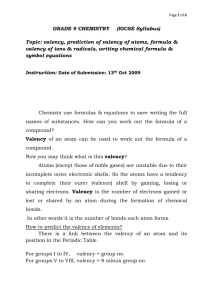

Abstract Building the valency lexicon of Arabic verbs The proposed contribution will describe the building of a valency lexicon of Arabic verbs using linguistically annotated corpus, The Prague Arabic Dependency Treebank (PADT), as its primary source. Valency of a verb is a set of its obligatory and/or optional arguments potentially or actually realized in an utterance. Valency is not predictable automatically. Valency information is useful in restoring the syntactic structure of an utterance, and has consequences for the study of the meaning. Valency lexicons can find application in automatic parsing as well as in language generation. The primary goal of the study is to prepare theoretical and methodological background for creating the valency lexicon of the most frequent Arabic verbs based on the theoretical framework of Functional Generative Description (FGD). This Arabic lexicon, inspired by The Valency Lexicon of Czech Verbs VALLEX 2.0 ([http.//ufal.mff.cuni.cz/vallex/2.0; Lopatková et al., 2006; Žabokrtský, 2005]), may be used in particular for the tectogrammatical annotation of the PADT as well as for the proposed second edition of the corpus-based Arabic-Czech Dictionary ([Zemánek et al., 2006]). PADT ([http://ufal.mff.cuni.cz/padt/PADT_1.0; Hajič et al., 2004]), a multi-level linguistically annotated corpus of Modern Standard Arabic consists of three levels of annotation – morphological level, analytical level of surface syntax, and tectogrammatical level describing the linguistic meaning of the sentence. Verb valency is studied on the second and especially on the third level of annotation, which provide us via dependency trees with relevant information about all syntactically dependent arguments on particular verb or verbonominal derivative. According to the valency theory of FGD also applied in the Czech lexicon VALLEX 2.0, each verb (lexem) has at least one valency frame. The exact number of these valency frames depends on the number of meanings of particular verb (lexical units). The valency frame consists of both obligatory and optional inner participants and obligatory free modifications ([Panevová, 1994]). For expressing relations between a verb and its complementation, FGD uses different functors. These functors are divided into actants (inner participants) and free modifications. The entire number of actants is five (Table 1) and there are many different free modifications which denote various types of adverbial complementation. Table 1. Types of actants (inner participants of the valency frame) and their examples illustrated on English sentences ([Lopatková et al., 2006: p. xvi]). Actant Meaning Examples ACT actor ADDR addressee PAT patient I saw him. EFF effect We made her the secretary. ORIG origin She made a cake from apples. Peter read a letter. Peter gave Mary a Book. We believe that all the valency frames created on Czech and gathered in VALLEX 2.0 (about 6,500 valency frames for about 2,700 lexeme entries) can serve as a useful source of information for describing the valency in other languages taking into consideration their natural word order. It is possible to compare these valency frames with relevant data in Arabic and to preserve them, if they match, or to modify them, if they differ. As an example, the valency frame of one particular meaning of very frequent Arabic verb qāla (“to say”) can be mentioned (Table 2). Its valency frame corresponds to the Czech verb říci with the same meaning. Table 2. An example of the valency frame of the Arabic verb qāla (“to say“). qāla subject li- (preposition) c an (preposition) object/’inna (conjunction) to say ACT ADDR (optional) PAT (optional) EFF someone (subject) to somebody about something something/that Example from the corpus (shortened): can about al-calāqāti qāla the-relations [PAT] he-said [PRED] al-wazīru the-minister [ACT] about the relations the minister said that... Comment: Optional actant ADDR (addressee) was not realized. ’inna... that [EFF] In case of Arabic, verb valency should be studied in close connection with its verbonominal derivatives – participle (active and passive) and verbal noun ( in traditional Arabic linguistic terminology). Not only can these bear similar syntactic function as the verb (e.g. participle as a predicate in nominal sentences), but in many cases they preserve the same or almost the same valency frame as the verb they are derived from. As an example for (“to demand”) preservation the valency frame (Table 3), we can mention the verb (“demanding”) and verbal noun and its active participle (“demanding, demand”). (“to demand”) Table 3. Valency frame of the Arabic verb to demand subject object bi- (preposition)/’an (conjunction) ACT ORIG (optional) PAT someone (subject) of somebody something/that Examples from the corpus (shortened) verb she-demanded [PRED] bi- al-wikālatu al- i the-agency [ACT] of-the-unions [ORIG] i... an-analysis [PAT] the agency demanded an analysis of the unions... active participle ... qijādata ’l-ğajš bi-’iqāmati (he) demanding of-a-leadership [ORIG] the-army establishing [PAT] a-dialog (he) demanding of the army leadership to enter into a dialog verbal noun reaches an-extent mutālabati ’l-zawğati a-demand of-the-wife [ACT] bi-’lthe-separation [PAT] ...to the extent that the wife demands to separate Comment: Optional actant ORIG (origin)was not realized. The paper will also present some of the tools and methods for querying the syntactic structures of the treebank. Based on our previous experience, the search tools (used in the “project”) will include TrEd, Netgraph, and Xaira. TrEd and Netgraph allow structural queries into the trees. Xaira searches in linear text, but the underlying data for it can include e.g. annotations of functors and surface syntax (analytical) functions. As the primary lexical resources, we will use the Czech Vallex 2.0, Hans Wehr’s Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, the Czech-Arabic Dictionary, and the ElixirFM lexicon derived from the Buckwalter lexicon (allowing transformations/derivations between verbs/participles/verbal nouns). References BADAWI, Elsaid, CARTER, M.G. and GULLY, Adrian. Modern Written Arabic : A Comprehensive Grammar. London : Routledge, 2004. HAJIČ, Jan, SMRŽ, Otakar, ZEMÁNEK, Petr, PAJAS, Petr, ŠNAIDAUF, Jan, BEŠKA, Emmanuel, KRÁČMAR, Jakub and HASSANOVÁ, Kamila. Prague Arabic Dependency Treebank 1.0. LDC catalog number LDC2004T23, 2004. LOPATKOVÁ, Markéta, ŽABOKRTSKÝ, Zdeněk and BENEŠOVÁ, Václava. Valency Lexicon of Czech Verbs VALLEX 2.0. Technical Report TR-2006-34, Praha : ÚFAL MMF UK, 2006. PANEVOVÁ, J. Valency Frames and the Meaning of the Sentence. In Luelsdorff, P.A. (ed.). The Prague School of Functional and Structural Linguistics. Amsterdam – Philadelphia : Benjamins Publ. Comp., 1994, p. 223-243. RYDING, Karin C. A Reference Grammar of Modern Standard Arabic. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2005. WEHR, Hans. A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (Arabic-English). 4th ed. Urbana : Spoken Language Services, Inc., 1994. ZEMÁNEK, Petr, MOUSTAFA, Andrea, OBADALOVÁ, Naděžda and ONDRÁŠ, František. Arabsko-český slovník [Arabic-Czech Dictionary]. Praha : Set Out, 2006. ŽABOKRTSKÝ, Zdeněk. Valency Lexicon of Czech Verbs. PhD thesis. Charles University, 2005.