If you want to read the entire chapter, this is where you go.

Sizing up the Learner:

Step 1 of The 4 Steps

Chapter Introduction

In Unit 1 you learned the importance of cognitive load theory.

As a designer you do not want to overwhelm or underwhelm your learner. You want to present just the right amount of content, and to present it in a way that is germane and meaningful.

In Unit 2 you learned information processing theory as well as the 4-step design process you will use for the rest of the semester. We now begin the first of the 4-steps with Step 1:

Sizing Up the Learner. Here you learn research methods that turn you into a cognitive-load detective.

Sizing up the learner is a step that involves getting to know your learner in order to figure out what they need to know. The expression “getting people from point A to point B” applies to this step. Cognitive load theory helps us fill that space between A and B; and helps to identify the optimal type and amount of instruction needed. Our goal to help the learner get to point B as efficiently and effectively as possible.

While it might seem that we need to collect vast amounts of data, to really get to know the learner, we try instead to narrow the data we gather. We focus on identifying learner characteristics and experiences relevant to our instructional goals. As we sift through the data we collect, we begin to move towards the identification of what an optimal cognitive load might be. We do not go into learning styles information, instead we focus on a cognitive structure all humans share.

Chapter Outline

1.

Focusing on the critical information

2.

Detective Work a.

Information sources b.

Usability testing c.

Becoming a qualitative researcher

3.

Relevance to Cognitive Load Theory

4.

What about Learning Styles?

Chapter 6--- 1

Focusing on the Critical Information

(Getting from point A to point B effectively and efficiently).

You focus the Sizing up the Learner Step on learner characteristics that influence attainment of an instructional goal. You seek answers to questions such as:

What are the learner's prior experiences, and how do those relate to the proposed instruction?

What are learners likely to know already?

Where should learners begin?

How will learners use the information?

How motivated are the learners?

What would motivate the learners?

Most people like the idea of starting with learner analysis and enthusiastically embrace the idea of issuing learning styles inventories and collecting information on likes and dislikes.

While information of this nature is nice to know , it often does not direct us quickly to information we need to know . For example, asking a learner what their favorite dessert is will most not help you create better instruction if the topic is unrelated to desserts. A dessert might be a great incentive or reward for a learner, but you first need to start with what exactly the learner must learn.

Obviously the best place to start is to determine what the learner goal is, which happens to be Step 2 (stating the outcome) of the 4 steps. Why not start with Step 2? The truth is you could. You’ll find that The 4 Steps tend to take place simultaneously. We present them sequentially because that is the easiest way to explain what is going on, but in reality many of the decisions take place concurrently. There will be times when reading that you will wonder why information is placed where it is. For example, in this chapter we cover usability testing, a topic usually addressed in Step 3: Making it Happen. We could cover usability testing in a different chapter, and it would make sense both places. We cover it here because usability testing is a type of learner analysis, the main topic of this chapter. The point is that this process, even when the phases are called Step 1, 2, 3, 4 - is often difficult to separate into steps at all. You will experience occasional overlaps as your read this book. It is OK, in real-life design you also have

Chapter 6--- 2

simultaneous experiences, and it will happen much more often than it does in this book.

Sizing up the Learner is the first step because it establishes a common ground from which to start. We have all been learners.

Additionally, many of us do consider the learner first. We are often handed the instructional topic along with overall goals and are asked to start with existing information. Often the first things we think of are learners. We might have information handed to us first, about what to learn, but to really work well with that information we need to know who the learner is and what they will be doing with that information.

The important point for this first step, Sizing up the learner , is that you focus on learner characteristics that impact the task or learning goals you want achieved . Things like reading level are important if the task involves reading. Typing speed and accuracy matters if the task the learner needs to perform involves minimal error and maximum speed, perhaps in a fast paced data entry environment. Fortunately, the critical learner data often evolves as a part of the prototyping process. You often learn the important audience characteristics while the audience tests the prototype (an early version of the lesson).

For example, you might be asked to design instruction for group of critical-care nurses. Due to their expertise in nursing, you would not start at the beginning and cover information they already know (and contribute to extraneous load.) Instead you might create a job-aid of critical, but familiar content that prompts memory, but does so in a way that establishes some type of context familiar to the nurse. If that example confuses you, think of a recipe - you do not need to memorize the cooking instructions for lasagna in order to make it - you rely on the recipe to prompt you through the steps when you are in a kitchen. The same goes for pumping gas at a gas pump. If you go to a different gas station, the instructions there will trigger your memory enough to know how to use the nozzles and buttons to fill your tank.

Your goal as a designer is to answer this question: What does the learner really need to know or be able to do in order to problem solve in the future or to perform a task? We’ll write it once more for added emphasis.

Do not underestimate the power of the question “What does the learner

really

need to know?”

Chapter 6--- 3

This isn’t a question that is easily answered and unfortunately many people creating instruction address the question at a superficial level. As an instructional designer you are paid to answer this question using resources that others do not even think to consult.

You might answer the question “what does the learner need to know” by looking at the way something has been taught or presented in the past. This often involves getting a hold of a book and repeating all the information in the book in the class.

This doesn’t work, because the book:

may have outdated content

may not have relevant (germane) information

will likely have too much information (extraneous load)

may not present the information optimally, especially if the information has a high intrinsic load.

If you doubt this, think back on your own experiences in training or education environments. How many times did you walk out of a class or a training session with the feeling that “wow, that was really good! I learned so much there. My time was wellspent. The things I really needed were taught.”

To avoid creating mediocre lessons that do not teach anything new (or needed), you’ll do your homework, which involves finding information from a number of sources.

So far, much of what is covered in this chapter is fairly abstract. We talk about learners - who could be anybody, content

- which could be anything, and some unique goal - also open for grabs. Before you float off into space, let's make the chapter a little more concrete. For now, assume you have been asked to teach about dieting. Assume your learner is overweight. Also assume that you have been told that your goal will be to get the learner from point A to point B in a very tangible way. You figure out that your learners are all between 20 and 30 pounds overweight. They are all on the edge of obesity. We will work with this scenario throughout this chapter. Later, you can substitute your learner, your content, and your goal as you go through learner analysis with your own content.

Detective work

Put on your detective hat when you seek information about your learner (the dieters). This is the key difference between traditional education/training courses and instructional design.

Chapter 6--- 4

You are asked to discover information (of importance to your dieter). Keep the phrase "think like a detective" in mind as you read ahead.

For those of you who like sequential steps ( 1, 2, 3) consider yourself now at step 1. You are ready to gather information about your dieter. You will be asking questions and observing.

Think of a detective's little black book. You will ask a number of people who know about nutrition and obesity a number of questions, you will ask your dieters questions, and, you will observe your dieters, perhaps as they go through a grocery store, or select recipes to cover a week. During the process you will record that information in a little black book (of sorts).

Or, you can use the forms below to guide your inquiry.

Information Sources

You will collect data from:

1.

learners (your dieters)

2.

a subject matter expert (a sme - dietician)

3.

documents ("how to diet books", recent journal articles on dieting, special cookbooks…)

4.

observations of the performance context (you will follow your dieter around a grocery store or watch them as they create a grocery list or select recipes)

The four tables below (Tables 1 - 4) help you collect this type of information. While these tables do not have a complete listing of all methods available for collecting data, they do provide a variety of methods for triangulating (consideration of multiple sources) information.

Each of the tables uses a different information source.

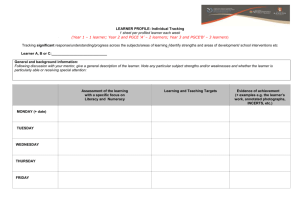

Table 1 shows the types of tools used to gather data from a representative member or members of the learner audience.

Table 2 shows the types of tools used to gather data from a subject matter expert (a person who knows what the learner needs to know).

Table 3 shows how you might gather relevant data from materials and information .

Table 4 describes the tools and methods used when observing the learner or the environment in which the learner will demonstrate what they have learned. All of these tools are useful ways to

Chapter 6--- 5

gather information that you need in order to "size up the learner".

Imagine that you filled in the tables below to learn more about your dieters.

Table 1

Analysis Tools for Gathering Data from the Audience/Learner (the dieter)

Tools Example

Pre-tests

Surveys

True or false?

An egg is high in protein and carbohydrates.

If you could change one thing about

Interviews

Straw man (Show an example of something and get their response)

User-tests your eating habits, what would it be?

What food stimulates hunger for you?

Ice cream, for example.

These are examples of the top six workout videos. Do you do any of these exercises now? Which of these appeal to you most?

Require the learner test out evolving prototypes. Observe them as they interact with the product. Ask questions, and videotape interactions if necessary.

Chapter 6--- 6

Table 2

Analysis Tools for Gathering Data from a Subject Matter Expert

(A Dietician)

Tools

Interview

Example

You asked questions, such as:

“Ideally, what will the learner be able to do or what will they know after taking part in this instruction?”

Straw man (Show an example of something and get their response)

“What are the hot books in your field right now. What are professionals reading?”

Demonstrated an example and solicited feedback “This is a sample unit of instruction based upon our discussions. How accurately have I

Observation captured what you think is important?

Do you have suggestions?”

Observed the subject matter expert calculate fat, carbohydrate, and protein percentages when menu planning. You kept notes in a journal of what they did and said while calculating this information.

Chapter 6--- 7

Table 3

Analysis Tools for Gathering Diet-Related Literature or Recorded

Information

Tools Example

Curriculum materials Textbooks, lecture notes,

Related literature worksheets, videos, computer based-training, web information etc., dealing with nutrition and dieting

Suggested dieting books, journal articles, transcripts, etc.

Data

The physical presence of an observer or observers

Video Equipment

Statistical reports on dieting trends, calorie averages, unique dieting-related data, etc.

Table 4

Analysis Tools for Observing Good and Bad Dieters

Tools Example

You and perhaps several people observe how dieters create meal plans and shop for groceries.

Analyze a video recording of the of a dieter sometime during the week, in a food related situation..

These four tables show a few ideas for data collection; it is up to you however, to do the detective work and figure out who should be interviewed and observed and what exactly you must ask. Most likely you will pick and choose amongst the questions and forms above as well as use forms and questions you have created yourself.

Chapter 6--- 8

Usability Testing

At this point, assume that you've completed that first phase of a learner analysis, gathering data. Using the four forms above, you have gathered interesting information about your learners, the dieters. You are now ready for the next phase, usability testing, an optional step that you may elect to skip, initially.

(You will revisit this step later, perhaps as you take part in

Step 3, Making it Happen.)

This optional analysis presents another way to collect information about your learner - the dieter, through usability testing.

Usability testing is a method of assessing how effective, efficient, and appealing the instructional environment or product is to the learner. To do this step requires that you have existing or early versions of instruction ready for the learner to use. For example, you might have a computer-based (or paper-based) training on how to read food labels. You would observe a few of your dieters using early as well as later versions of the instruction and would gather a set of recommendations for improvement.

Usability is a term typically used in the context of technical testing to determine if an environment is error-free and easy to use, often a computer application of some sort. In this class we think of usability in a broader sense, not focusing exclusively on the technical issues (though these are important) but also focusing on the quality of the instructional delivery. We focus on how the learner appears to be accessing instructional content and engaging in learning activities.

This might sound as if we were advanced enough to attach probes to the learner’s head to track cognitive activity. While this may be something foreseeable in the future, at this time we are limited to what we gain from simple observation and interviews, which is actually quite a bit! If we are testing computer-based training, we observe and ask ourselves if the learner is actually clicking where they were supposed to click. Do they complete the activities as intended? Do they appear confused or frustrated? How are they performing academically?

User-tests start from the very first instructional prototype and continue until the final product is complete. Three phases of user tests take place.

Chapter 6--- 9

Phase one involves the designer’s overview of the product from a technical and instructional feature perspective.

Phase two involves a user talk “aloud” where the user talks aloud their impressions of the instruction while you observe and take notes.

Phase three involves testing instruction with a group of representative users, preferably five. According to Nielson

(date), five users will yield enough information for valid results. Users test the instruction and its interface.

Phase 1. Phase 1 provides a quick assessment of the effectiveness, efficiency, and appeal of existing or new instruction. Phase 1 is typically a check-sheet approach that gives you quick feedback on the overall usability of the product by examining the technical and instructional features of the instruction.

A technical user-test focuses on the physical attributes of instruction and any media it uses. Back to our dieting example, you might use Table 5 as you observe your learner using computer-based instruction, paper-based instruction, or other formats.

Chapter 6--- 10

Table 5

Technical User-Test Criteria

Task

Access to instructional unit

Action

Can open unit of instruction

Can start unit of instruction

Navigation through instructional unit

All links and page numbers

User reaction

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Can move forward and backwards

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Sees the bigger picture (perhaps with site map or menu)

Technical features functional

Can leave or exit instruction/can return

Embedded features such as calculators, drag and drop work effectively

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Peripheral features, such as DVDs work

Connectivity issues Internet speed is not a barrier

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Absence of “crashes” Yes____ No ____

Comment:

The instructional experience user-test.

In addition to making sure the instructional unit is working and accessible technically, you will user-test for instructional quality (see

Table 6). For this test you look at a number of issues.

Chapter 6--- 11

Table 6

Instructional Quality Criteria Using Mayer’s Select, Organize, and Integrate Criteria

Select, Organize,

Integrate

Does the design facilitate noticing the most important information? (such as a food label).

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Does the design facilitate learner organization of material? (Is there a

Yes____ No ____

Comment: procedure on how to read an interpret the food label?)

Does the design facilitate learner transfer? (Will the instruction provide opportunities for the dieter to plan lowcalorie nutritional menus).

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

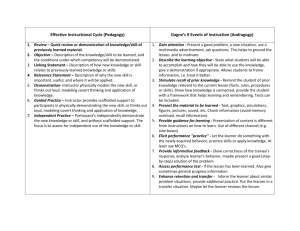

Table 7 shows how you can quickly check instructional quality by assessing how closely the unit of instruction follows our model of instruction (the select, organize, and integrate approach learned in Chapter 1, Theory). We also introduce Gagne’s nineevents of instruction within this context. Gagne's nine-events of instruction are well known and followed, but you could use other models in the left column as well. The important message here is not related to which overall learning model you use, but how to focus your attention on how the learner select, organize and integrate information within any model you choose.

Chapter 6--- 12

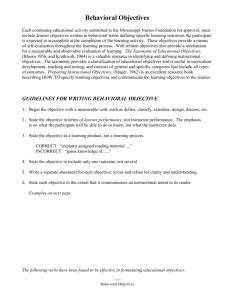

Gagne's nine events (from The Conditions of Learning , first published in 1965) of instruction are:

1.

Gain attention (to help the learner select)

2.

State objectives (to help the learner select)

3.

Stimulate recall of prior knowledge (to help the learner select, organize, and integrate)

4.

Present information (to help the learner organize)

5.

Provide learning guidance (to help the learner organize)

6.

Elicit practice (to help the learner organize)

7.

Provide feedback (to help the learner integrate)

8.

Assess performance (to help the learner integrate)

9.

Enhance retention and transfer to the job (to help the learner integrate)

Table 7

Instructional quality criteria using Gagne’s 9 events of

Instruction

Gagne’s events * of instruction (or other instructional model)

Does the design facilitate learner attention? (Is the instructional topic

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

*Each event is designed to facilitate selection, organization, and integration. clear - do dieters immediately focus on food labels?

Does the design provide overviews, advanced organizers, and state objectives? Is there some type of story or picture that describes a number of food label items?

Does the design stimulate prior recall? Will the

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment: dieter correctly use fat and carbohydrate percentages?

Does the design present information?

Do the workbook cover the six essential nutrients?

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Chapter 6--- 13

Does the design provide guidance?

Are steps clearly identified so that the dieter knows what to do on their own, without help.

Does the design provide practice/performance opportunities? Are there sample labels and meal plans for practice?

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Does the design provide feedback?

Does the learner know if their calculations are correct.

Does the design assess learner performance? Does the dieter see comparative or normative data.

Does the design assess transfer of

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment:

Yes____ No ____

Comment: learning? Does the dieter correctly interpret food labels two weeks later

Phase 2. During this step you ask the learner to talk aloud what they are thinking while they work through your instructional prototype. The purpose of the talk aloud is to see the instruction from the learner’s eyes. The most pure talk aloud method involves videotaping the users as they work through instruction, watching eye movement, body posture, and facial expressions in a non-obtrusive manner. Unless you have access to a usability setting that uses videotaping and other high tech approaches, you will conduct a simple talk aloud procedure.

In a talk aloud procedure you simply observe the learner while they are working their way through instruction. You ask them to

Chapter 6--- 14

talk out their thoughts while they go through the instruction, sharing with you what they understand and what they don’t understand. Table 8, derived from Tessmer (1993), shows you a script and procedure we follow when conducting a talk aloud protocol.

Table 8

Talk Aloud Usability Test

USER-TEST

A BEGIN THE USER TEST

Introduction script:

Get permission to use tape recorder:

B OBSERVE

Remember these things:

Thank you for testing this instruction for us. For the next

(insert approximate time) minutes, I’d like you to tell us what you think of the instruction that we are creating. Your opinion is very important to us because it helps us create instruction that works and that people enjoy using. When you don’t like something you must let us know. When something is hard to understand and unclear we want you to point it out. We don’t think you are dumb, instead we are happy that you found the error before it confused many more people.

You will be using what we call a talk aloud procedure.

Basically you share your thoughts with us. For example, you might start using the program and say something like this “OK,

I am looking at what appears to be a menu. I see several columns of words. I’m not sure what I am supposed to do? Am I supposed to click? I’ll try it. OK, that worked. Now I see something new. Wait a minute, I don’t want to be here, I want to go back to that previous page…” (You might want to demonstrate the talk aloud with some instruction.)

Do you understand what to do? Are you ready to begin?

I would like to tape record your talk aloud comments. Is this ok with you? (if it is not OK make sure it is OK for you to take notes.)

The user might feel self-conscious at first. To help them feel more comfortable try some of these techniques:

talk to them from time to time, reminding them how grateful you are to have their opinion.

take notes so they don’t feel like you are staring at them.

ask them things in a friendly way. For example, “I noticed you clicked on this button and not this button.

Can you share why?, is friendlier than: “Why did you click on that button?”

C END

Conclude the interview

Thank you for your time. We appreciate your help.

Chapter 6--- 15

Phase 3. Although Phase 3 is critically important, many people do not have the time to conduct it. If you do have the time,

Phase 3 provides you with additional information from a group of approximately five learners who test the instruction while you observe and take notes. You watch to see what types of problems emerge in a group, rather than a one-on-one, setting. What types of questions are asked, where are users confused? At the conclusion of the test, you might ask several open-ended questions, such as:

What did you like about the instruction? Why?

What did you dislike about the instruction? Why?

If you could change the instruction, how would you do it?

You continue to test groups of 5 until you no longer hear new suggestions or reactions.

Becoming a Qualitative Researcher

Imagine now that you have collected as much information about your learner (the dieter) as possible. You've been a good detective. Interviews with learners and a subject matter expert

(a dietician), data from relevant documents, and observations of the dieter as they plan menus have told you quite a bit about your learner. You should have enough information for a rough estimation of Point A and Point B (where the learner is now and where you want them to be.) We are now at Step 2.

You have a general, if fuzzy, learner goal statement identified:

The learner/audience will adopt practices of healthy living

that lead to reduced weight.

It’s time now to turn your focus on what to do with that data, and how to analyze it.

Working with your data

Here you stop collecting data and start thinking about the data in ways that you can turn into instruction. It is here that you continue to be like a detective, but one that has some qualitative research skills .

You arrange, rearrange, chunk, and categorize the information collected thus far into meaningful groups, assigning descriptive

Chapter 6--- 16

labels or codes to your groups. If this sounds too abstract, it might help to think of this stage as writing an outline. You come up with the words (codes) to create the outline. If you can’t think of anything, start with the codes/categories like

“observable” and “non-observable” or “things the learner does” or “things the learner knows”. You can also label and arrange index cards using your code or category names, as a substitute to or in conjunction with your outlines. The goal is to create chunks of related information.

You then go through a second level coding, or outlining. Here you find different ways to categorize, chunk, or outline your content. Think of moving index cards around again, or creating new outlines. You might have to create new cards for new thoughts or new outlines. Essentially this is your opportunity to identify themes from the previous codes. Attempt to form meaningful categories. If possible, create know, do, and feel

(or value) categories.

For example, it might help you to think of your data as a big pile of Legos (see Figure 1). It is your job to think about these Legos, to make sense of them, to find some patterns and some relationships. This step is not one that can be prescribed.

In this step you become a qualitative researcher because you organize information and look for themes that will have meaning to your audience and will help them learn new information. This is a tough step for a beginning designer. To help yourself through it, focus on sorting information into know, do, and feel categories if you can. If you can not, do not worry, some content may not fit the know, do, and feel framework.

Chapter 6--- 17

Figure 1.

Information Legos.

For purposes of instruction, we’ll say that after organizing and thinking about the information (see Figure 2) you are able to sort your data into do, know, and feel categories as follows.

Do: Reduce high fat and highly processed foods while increasing exercise.

Know: Understand the relationship between weight problems and consumption of high fat, highly processed foods, and minimal

Feel/Value: value health and therefore desire to adopt healthy habits

Chapter 6--- 18

Figure 2.

The Do, Know, and Feel clusters of data.

The Do data, Know data and Feel data can be thought of as your task and content analysis. Task analysis focuses more on what the learner does. Content analysis focuses more on what the learner must know in order to perform, or “do.”

Let’s say that once you have your data organized into Do, Know, and Feel categories, you decide that you want to take a more content/topic focus and further group your data (see Figure 3).

You choose this content/topic focus because it allows you to organize information into logical categories that the learner is likely to remember.

Chapter 6--- 19

Figure 3 . Data organized by topic and content

On the other hand, you might organize information by what the learner does, instead of knows. If this were the case you would organize by task.

Eventually you create organized information structures that relate to your overall goals in the form of very outlines or some structure with which you can work.

Relevance to Cognitive Load Theory

Important to this chapter is the proposition that a designer should work to reduce the complexity of information that is likely to overwhelm a learner, and to reduce or eliminate extraneous information altogether. At the same time, the designer needs to increase the load that is germane, or relevant to the learner. Fortunately, there is an assumed relationship between reducing one type of load and increasing the other. By decreasing demands of an extraneous and high intrinsic nature, you free up memory for germane load.

Most instructional strategies (the techniques used to reach out and grab the learners' mind) are proposed as methods for reducing cognitive load. Sequencing strategies, scaffolding

Chapter 6--- 20

strategies, use of metaphor and analogy, use of story, and many other approaches to make learning more effective, efficient, and appealing essentially have the same goal – to reduce cognitive load. Even the expression “a picture speaks a thousand words” addresses cognitive load.

Following are brief descriptions of a few of those strategies and their relationship to cognitive load theory. For our purposes, we’ll consider sequencing, or organizing the presentation order of instructional information as an overall strategy for reducing cognitive load. Many textbooks refer to

“identification of prerequisite knowledge” when they address sequencing. What does the learner already know? What doesn’t the learner know? How can we use that to move the person from point

A to point B? As we conduct learner analysis we need to look for the stories, metaphors, and other hooks that will appeal to the learner.

Simple to complex sequencing

Presenting simple information before complex information is one sequencing strategy that theoretically provides learners with prerequisite knowledge required for understanding new content.

As such, effective sequencing strategies reduce cognitive load.

This type of sequencing is essentially a scaffolding strategy.

The goal is to help build a memory structure (schema) relevant to the content. Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development, the argument to place instruction at the intersection of where a student is and where you’d like them to be, can also be thought of as simple to complex, or familiar to unfamiliar sequencing.

Familiar to unfamiliar sequencing.

Presenting information in the context of how it is experienced in life, is another. For example, metaphors and stories fall into this category.

Metaphors and analogies. Instructional metaphors compare new content to familiar to a description of something similar for the sake of making a comparison. For example, an instructional designer is often compared to an engineer (Smith and Ragan).

[Instructional designers and engineers] plan their work based upon principles that have been successful in the past – the engineer on the laws of physics, and the designer on basic principles of instruction and learning. Both try to design

Chapter 6--- 21

solutions that are not only functional but also attractive or appealing to the end-user. Both the engineer and the instructional designer have established problem-solving procedures that they use to guide them in making decisions about their designs. (p. 2)

Most people are familiar with engineering as a profession, but are not as familiar with the profession of instructional design.

Many people are helped by the comparison. In this respect, intrinsic load (the complexity of instructional design) is made lighter by increasing germane, or personally meaningful, load.

Stories. The argument for story strategies follows. Human schemas are organized into story structures that allow the anticipation and interpretation of new information. Children as young as three recognize that stories have beginnings and endings. “[Stories] set up an expectation at the beginning, this is elaborated or complicated in the middle, and is satisfied in the end” (Egan, 1986, p. 24). Learner’s use that structure to suspend immediate understanding with the knowledge that there will be a middle (a part that explains things) and an end (new understanding).

Sequencing Challenges

Despite their promise, the sequencing strategies listed above, the saying that pictures speak 1,000 words, and other proposed solutions to cognitive load are only as effective as their design. If a sequencing strategy isn’t part of a learner’s experiences, it will place an undesired load on memory. Even with the best of intentions, we may actually increase cognitive load when attempting to decrease it. Poorly designed images will create confusion instead of clarity. Instead of speaking 1,000 words, they speak thousands of meaningless words.

Simple to complex sequencing challenges

One common mistake with simple to complex sequence is the presence of too much simplicity. Information is dummied down to the point many people feel insulted or even cheated. Visual displays of instructional content have so often been associated with this experience that the phrase “I just looked at the pictures” is often used to describe a meaningless reading experience.

Familiar to unfamiliar sequencing challenges

Chapter 6--- 22

As an extreme example, think of a calendar arranged in alphabetical order! Although we are all familiar with the alphabet, our seasonal experience with the months would be a more logical strategy. Imagine the load on memory if you needed to quickly check a date in July and found it located right after

January?

Poor analogies work the same way. For example, I once compared writing a dissertation to searching the Titanic (a buried ship) for its treasures. I wanted to convey that the writer has to explore, and dive deeply into information and ideas, immersing himself or herself time and again into the process, before they find the treasure, a dissertation topic. Later I learned that my

“sunken ship” analogy had an entirely different meaning. In the student’s minds, references to drowning, searching for money, and shipwreck were not reassuring, not to mention that few of them thought of a dissertation topic as a treasure. While I was trying to reduce load, I inadvertently increased it because students were wondering why I would try to discourage them. Even those who laughed at the analogy were distracted.

Designers use visual displays all the time to decrease load.

Many believe “ Every picture is worth 1000 words, so I’ll add a lot of pictures.” There are many, many examples of pictures that don't work. Consider the Florida ballot problem as just one.

Likewise, story telling does not always reduce load either.

Consider these two reactions to the same story, told in the same class. I love this example, because you can relate to it, it is the story that you are now reading in this class.

This student liked the story . “I was surprised that I enjoyed reading this book. The information is easy to follow and easy to understand, even for a foreigner like me. The most important of all is that it’s fun to read. The way you used a story, illustrations and analogies to explain the concepts is excellent. What you said “this book teaches you how to do this using a simple model that is easy as ABCD to remember” is true. I like it! Your book reminds me of something about writing: “ I have just found out what makes a piece of writing good… it is making the sentences talk to each other as two or more speakers do in a drama.”

This student disliked the same story . “I have a family, a house, cars, as well as rental properties to maintain; I try to stay involved in my community, and have a career. Adult learners like me don’t have time to read through such drivel

Chapter 6--- 23

to get meaning out of the course’s text that they are taking.

If I want a good read it wouldn’t be this. Dump the “WARM &

FUZZY””

The lesson here is that what may be germane load to one person may be extraneous load to another.

What About Learning Styles?

Many of you are probably wondering about this question just about now. You would think that learning styles would be a key topic in a learner analysis chapter. I like them myself, and have found they explain many mysteries to me about why people have such different reactions, similar to the story above.

While different styles of learning are important, we do not consider personality theories (such as Myers-Briggs and

Gardner’s intelligence types) in this class. First, this text is an introductory text and we do not have time to cover all the different learning style theories. Let's start with a good design, a design that can reach as many people as possible. It is difficult enough to make one good unit of instruction, let alone several units to accommodate different personality types.

Therefore, we focus on a generic model that you are likely to be able to integrate later with a particular learning style approach.

Second, we agree, overall, with Merrill’s (2002) argument on learning styles. Individuals do differ in cognitive, affective, and physiological ways . These differences, however, do not require development of many different types of instructional strategies.

“[Learning styles] will make a difference, but not in the fundamental components of the instructional strategy.” P.

101.

As instructional designers, in this class and elsewhere, we can modify instruction for individual differences, even if not for different learning styles. We do so by varying:

content

the number of examples

the sequence of examples

the attention focusing features according to different types of learners

Chapter 6--- 24

You may find yourself disagreeing with this approach. That is

OK. You can go back to a learning style focus after this class is over. I will at least know that you are aware of an alternative approach to consideration of learning styles.

Know These Terms!

Audience analysis – involves asking a number of people a number of questions.

Content analysis – focuses more on what the learner must know in order to perform, or “do.”

Instructional experience user-test – focuses on the instructional quality of your unit of instruction.

Learner-centered design – a process that involves the learner in the developing instructional product.

Subject matter expert (SME) – person qualified to provide content information relating to specific topics and tasks.

Talk-aloud procedure – a user talk “aloud” where the user talks aloud their impressions of the instruction while you observe and take notes.

Task analysis – list of procedures for analyzing the information needed to achieve the objectives. Task analysis focuses more on what the learner does.

Technical user-test – focuses on the physical attributes of your unit of instruction and the media it uses.

Triangulation – consideration of multiple sources to clarify and validate information.

Usability testing – a method of assessing how effective, efficient, and appealing the instructional environment is to the learner.

Chapter 6--- 25

Summary

In the previous chapter you learned about The 4 Steps for creating instructional design. This chapter covered the first of

The 4 Steps, Sizing up the learner.

You learned how to collect information about your audience by acting like a detective, triangulating data sources (interviews, observations, reports…) and conducting usability tests

(technical walk troughs, talk aloud procedures...) By testing your instruction early on, you avoid costly errors down the road when it might be too late or too costly to change instruction.

Once your data is collected, you take on the role of a qualitative researcher. You read and re-read the information and sort it into knowledge (know), skill (do), and attitude

(feel/value) categories of information, which become core design elements.

Throughout the learner analysis process you assess potential cognitive load issues. Data may indicate certain types of information will be extraneous for your learner. Other data may indicate certain types of information will be germane. Your goal will be to find some balance, and to strive for instruction that is germane.

This chapter does not cover different personality theories and how you might adapt instruction to different Meyer’s Briggs types, the Kolb Inventory types, or to Gardner’s 8 intelligences. Adjustments you make to account for differences will take place in how you arrange information for selection, organization, and integration. By varying presentation, content, the number of examples, and their sequence, you are able to create instruction that learners are able to adapt or use in unique ways.

The next chapter moves to the second of The 4 Steps, Stating the

Outcome. Here you take the information gleaned from this step and create specific learning objectives.

References

Merrill, D, M. (2002). Instructional strategies and learning styles: Which takes precedence? In R. A. Reiser & J. V. Dempsey

Chapter 6--- 26

(Eds.), Trends and issues in instructional design and technology

(pp. 99-106). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Nielson (

Tessmer M. (1993). Planning and conducting formative evaluation:

Improving the quality of education and training. London: Kogan

Page.

\

Chapter 6--- 27