Nickerson`s notes on Dr - Ontario Chapter, Association of

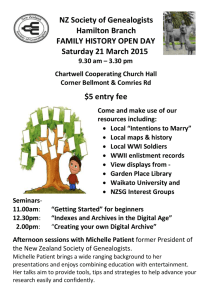

advertisement

Nickerson’s notes on Dr. Wilkinson’s PIPEDA talk, Feb.7, 2006 Before beginning her talk, Dr. Margaret Ann Wilkinson informed us that she is planning to write a series of four articles for OGS Families. The topics would be: 1. 2. 3. 4. The effect of PIPEDA on the research amateur genealogists do. The effect of PIPEDA on the research professional genealogists do. Copyright issues for genealogists of all kinds. Specific challenges posed by cemeteries. Dr. Wilkinson would appreciate us sending her any questions we might have, so she can incorporate her answers into the articles. Her e-mail address is: mawilk@uwo.ca. [Update as of April 10, 2006: Dr. Wilkinson is still planning to do the article series but the Editor of Families who took over in this New Year is not continuing and that a new Editor has yet to be appointed. The series will be delayed as a result of these successive editorial changes. Nevertheless, questions are invited and it is to be hoped that the series will appear soon.] The idea of protecting personal information in Canada began only a ¼ century ago. It started in the public sector, first with the federal government and in Quebec and then spreading gradually throughout the provinces and territories. Only Newfoundland has yet to declare in force a full scheme for protection of personal data in the public sector. Although all the other territories and provinces have enacted full regimes in the public sector, these provinces and territories differ about exactly which public sector organizations are covered by the legislation. In the public sector, personal information protections are combined with ideas about public access to information. Access to information legislation requires public sector organizations to give people access to information held by government unless there are particular legislated reasons why people should not have access. One reason for denying access to government-held information is that the information relates to an identifiable individual other than the person making the request. Personal data protection legislation gives the person who is the subject of the personal information held by those government organizations the right to access that information. The new federal legislation, Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), applies to private organizations across Canada and applies to any record held by an organization that pertains to a specific identifiable individual. This legislation applies to organization engaged in commercial activities that hold records. It doesn’t matter who originally created the record, only who is holding the record now. The new PIPEDA legislation, that came into full effect on January 1st 2004, protects personal information held by private sector organizations. It says that the private sector organizations cannot give out information about identifiable individuals except to the individuals who are the subject of the information. To the individuals who are identified in the record, there is a requirement that access be given to the record. An organization governed by PIPEDA is defined as any individual person, company or group association that is engaged in commercial activities. Professional genealogists would fall under PIPEDA. There are a few types of activities that are exceptions to the reach of PIPEDA: journalistic, literary and artistic activities – but not genealogy. [Note: Quebec was the first province to have personal data protection legislation that covered the private sector. Several others also have it now – but PIPEDA applies in provinces where there is not provincial legislation. Audience member Paul Leclerc drew to everyone’s attention the following exception from s.1 of the Quebec legislation: “This Act does not apply to journalistic, historical or genealogical material collected, held, used or communicated for the legitimate information of the public.” It may still be queried whether professional genealogists reporting only to their clients would be able to benefit from this exception because they might not be considered to be working “for the legitimate information of the public.”] There is also a time limit of 20 years after the death of the individual to whom the recorded information relates, or 100 years after the record was created, whichever is shorter. So, after 100 years has elapsed since the record was created, or 20 years after the subject dies, a private organization is permitted to release their personal information, but they are not required to do so. PIPEDA is federal legislation that applies to all private sector organizations engaged in commercial activities across the country except those in provinces that have their own personal information protection legislation that has been accepted by the federal government as equivalent. Quebec, for example, has its own legislation that was accepted immediately by the federal government as equivalent to PIPEDA. Ontario so far has only developed its own legislation covering the medical sector (PHIPA): in all other sectors, PIPEDA governs commercial organizations in Ontario. What this means for professional genealogists is that under PIPEDA we cannot collect information about anyone living without the consent of that person. Nor can we collect information about persons who have died within the past 20 years. Our clients can only give consent to collection of information about themselves, not information that identifies other individuals. The argument that a client can make a professional genealogist somehow the client’s agent and that this then would permit the collection of information about individuals other than the client, without those other individuals’ consents, is not an argument that is likely to succeed when challenged. There is no concept of agency in PIPEDA. If our clients send us information, as professional genealogists, about their spouses, siblings, parents, etc., and these people haven’t been dead for over 20 years, PIPEDA requires that we not collect or used that information or give it out to our clients. We are meant to collect information about such spouses, siblings, parents, etc. directly from the spouses, siblings and parents and receive from each express permissions to report that information to our client as well as additional permissions to make such other uses of it as we intend when collecting. PIPEDA governs the information in the hands of the professional genealogist, irrespective of the source of that information. So, information may be publicly available to clients about other members of their families, which they can gather as amateur genealogists but which, in our hands, as professional genealogists, would be subject to constraints imposed by PIPEDA. For example, information on persons living or dead within the past 20 years that comes into the hands of the professional genealogist from the 1911 census that is about individuals other than the client may not be able to be passed on to the client from the professional genealogist because it is about individuals other than the client and the professional genealogist has no consents from the individuals who are the subjects of the information to pass it on to the client. The same applies to newspapers, land records, wills, etc. (it also applies to information from international sources, such as the 1910, 1920 and 1930 US censuses etc.: this is because the legislation would apply to all information about identifiable individuals that is held by Canadian professional genealogists in provinces governed by PIPEDA, without regard to the sources from which the information was gathered). What are the penalties for non-compliance with this legislation? The federal Privacy Commissioner will investigate is anyone complains to him/her (or the Commissioner has the power to investigate on his/her own). If the Commissioner judges an organization to be in contravention of PIPEDA, he/she will give an opinion against the organization. This can be made public (internet etc.). The organization (the professional genealogist, in our case) will be told to stop what it is doing. The federal Commissioner does not make legally binding orders, but if the organization does not comply with the Commissioner’s opinions in the matter, the Commissioner can take the organization to Federal Court. Moreover, under PIPEDA, the complainant can get an award of damages ($$) by court order from the organization. Glimmers of hope: 1. This legislation has not been in place long and has not been tested by the courts. It is not absolutely clear how it will be applied in practice. It is possible, for example, that the “literary” exemption could be successfully used by a professional genealogist preparing a family history to defend against a complaint brought by an individual. 2. The Quebec legislation, as discussed above, has an exception for genealogy: it may be possible to lobby for the inclusion of an exception for professional genealogists in PIPEDA and every piece of personal data protection legislation for the private sector in Canada. Our Option 1. Do nothing and wait to see how PIPEDA is treated by the courts when challenged (hoping of course that the challenge does not arise in a situation that involves any of us). 2. Prepare consent forms and start sending them to our clients and their relatives, etc., anyone from whom and about whom we might want to collect information. 3. Contact cabinet ministers (Heritage at the federal level, for example) and members of the legislatures and lobby for express exemptions “for genealogical purposes.”