Of DNA and History

During the hot and violent summer of 2002, while one after another suicide bomber was tearing

himself and society apart, a group of scientists gathered in Tel Aviv to discuss our common genetic

heritage. The meeting concerned “ancient DNA,” which means DNA, the substance of genetic

inheritance, as it can be found in anything no longer living. This brought together participants from

around the world, ranging from forensics experts to anthropologists, archaeologists, and molecular

biologists. Like fossils themselves, DNA can sometimes persist for decades or millennia under the

right conditions. Over time, it degrades; its original configuration as chains billions of bases

(“letters”) long is converted to short pieces of perhaps several 10s or 100s of bases. It is as if a

newspaper is slowly ripped to shreds. The scientist’s job is to take the fragments of the newspaper

and then attempt to reassemble the news of the day from the individual phrases.

The task is not so hopeless as it sounds, however. We know very much about the human

genome, the DNA of a cell including all the genes specifying the instructions of life, and we

understand how it may change over time. Comparing the DNA from one individual – or fossil –

with that of another allows us to determine how closely related those two individuals are or were.

We can say, for example, if one is the offspring of another, or if they were likely members of the

same tribe. Given ancient samples, it may be possible to reconstruct events in human pre-history,

or events in recent times left unrecorded by our historians. Sometimes the DNA studied is not very

ancient, but nonetheless not from the living. The chief scientist in charge of identifying the victims

of the attacks on the World Trade Center was at the meeting and reported on the methods his team

devised. The researchers who identified the “unknown child” of the Titanic were also there. We

can also make inferences about the past by studying materials from the living.

A few examples suffice to illustrate the power and interest of this area of research. Several

years ago, studies of “molecular markers” – fingerprints based on differences in patterns within the

genome – showed that the Palestinians as a group are not, genetically, most similar to those from

the Arabian peninsula as might be expected if they were descendents of invaders, but rather are

most closely related to the Sephardi Jews. This indicates that a local indigenous population, of the

same ancestry as the original, per-Galut Israelites, were converted to Islam by a fairly small number

of clerics or soldiers and not that a large group of invaders settled in a land emptied by the Romans.

Among the Palestinians are Christians and Muslims, the Muslims being in the large majority. Islam

was founded and reached Palestine well before the Crusade arrived in the Holy Land, so it is easy to

think that the Palestinian Christians might have been Muslims converted, again at the sword, to

Christianity. However, the data reported at the meeting in Tel Aviv shows that the Palestinian

Christians are genetically closer to the Jews than to the Muslim Palestinians. This suggests that

they represent an ancient group of Judeo-Christians that persisted in Israel since ancient times, and

may have been already Christian when the Crusaders arrived.

Coming to a more local population, as we all know the archipelago between Sweden and

Finland is Swedish speaking. In the Middle Ages, it had the highest population density of the entire

Nordic region, due to its proximity to a steady source of food (fish) and major trade routes along the

Baltic. The islands today look more to Stockholm for their culture than they do to Helsinki, and it

one might think that, indeed, the settlers in ancient times came from the western side as well.

However, when Ålanders are tested genetically, it turns out that they are more similar to the Finns

of today than to the Swedes. One suspects that the wide channel separating the main island from

Swedish coast proved a greater barrier in ancient times than did the small bays stretching back to

the Finnish mainland, and the bulk of the settlers, but not the language, in fact arrived from the east.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the meeting, at least for me, was that of the Levis. Although

one’s identity as a Jew is fixed by the religion of one’s mother, the ritual status of a Jewish man is

determined by that of his father. Fathers who are Cohens have sons who are Cohens, and fathers

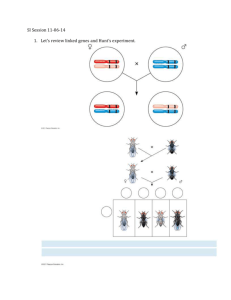

who are Levis have sons who are Levis. Biologically, our gender is also decided by our fathers:

one pair of chromosomes does the job. Boys have one “X” chromosome and one “Y”, girls are XX.

Since mothers are also therefore XX and fathers XY, the mother can give only an X chromosome to

the offspring, but fathers either an X or a Y, thereby determining the sex of the offspring.

Conveniently, then, both ritual status and gender rides on the Y chromosome: all boys who are

Cohens should therefore have a “Cohen” Y chromosome, and all boys that are Levis should have a

“Levi” Y chromosome. One can distinguish between the Y chromosomes of different groups by

“polymorphisms,” meaning differences in the pattern of molecular markers found on the DNA of

the chromosome. This clever observation was shown, in 1999, to be true for the Kohanim: the

present-day Cohens share a particular polymorphism found on the Y-chromosome; it is

considerably more frequent among this group than among other Jews, or among non-Jews. Details

of its change over time are consistent with an origin of the Kohanim as a distinct group in biblical

times. This was a deeply satisfying finding, confirming our ideas of Jewish peoplehood.

The same British research group that reported these findings went on to study the Levis.

Here, however, the results were surprising. The Levis split into two groups based on their Y

chromosomes, along the Sephardi – Ashkenazi divide. The molecular fingerprint of the Y

chromosomes of the Sephardi Levites fit into the Middle-Eastern framework well – it is highly

likely that the Sephardi Leviim are a homogeneous group descended of the Leviim of biblical times.

The Ashkanazi Levites likewise hold together as a single group. However, their Y chromome is not

of Middle Eastern origin – the ancestor of all current Askenazi Levites was a Sorb, a member of the

western-most Slavic tribe. The Sorbs came into contact with the Jews in late Roman times, when

Jewish settlements were founded in the Rhineland, and before the communities were organized.

The data indicate, then, that a woman married to a Levi bore a child by a Sorb man, but the male

offspring retained the religious status of his non-biological father. The social circumstances

surrounding this event are of course lost to time. One might wonder what happened to all the other

Ashkanazi Levites. The answer is that, through random processes, this one paternal line came to

replace all others, so far as the Y chromosome is concerned. The is not to say all Ashkanazi Levis

are half Sorb; because chromosomes assort independently, only the Y chromosome but not

necessarily others have persisted from the Sorb ancestor. As we all know, some men have many

grandchildren, and others none. Over time, some family lines die out, and others become very

widespread. This appears to have been the case among the Ashkanazi Levites.

For virtually all nations, their sense of identity is a mixture of cultural, political, and genetic

factors. People in Finland will say someone looks “unfinnish,” meaning that they do not share

variants of the few genes determining facial structure and hair color with the majority of Finnish

citizens. Nations also have myths about themselves – “we came from the Urals,” or “out of Egypt,”

which help solidify national identity. Modern genetic methods now enable evidence to be gathered

which support or do not support these claims, allowing us to propose explanations for events in prehistory. This is not the same as proving a certain tradition false, and the use of genetics to make

political claims is also suspect. An adopted child has no genetic claim to his new family, yet the

child inherits full social membership in that family.

The inhabitants of Åland may be amused by new data on their ancestry, but it is doubtful

that widespread knowledge of this will affect their autonomous status. The Christian Palestinians

would find their relative closeness to the Jews inconvenient, certainly not something likely to make

life among their Muslim neighbors easier. As for the Ashkanazi Leviim, there is a theoretical

problem. One cannot inherit Levitical status by adoption. If (when) the Temple is rebuilt, the data

would indicate that only Sephardi Leviim are suited for roles in the Temple. Of course, it will be

rabbis and not geneticists that will decide this, and I strongly suspect that the response from the

Rabbinate, if they were aware of the situation, would either be deafening silence, or a stony “who

asked you?” Perhaps it is just as well, for the sake of the unity of the Jewish people, such that it is.

As a small aside, genetic studies also indicate that among the general Western population, up to 10

% of children are not offspring of their socially defined fathers. For the September 11th victims,

when the data indicated this to be the case, the families were not informed. Again, the information

in most cases would not be welcome.

In the final analysis, it is important to remember that genetic fingerprints are like those on

our fingers – not very important except as identity tags. Sequencing of the human genome and

molecular marker studies have confirmed what we ought to realize anyway: that mankind is one

family, very closely related to each other, with genetic differences between individuals on the order

of a few tenths of one percent. If the Sephardi Jews are closest genetically to the Palestinians, the

Ashkenazi Jews are closest to the Syrians. It is this very closeness of all human beings, though, that

makes the political gulfs between us all the more tragic.

© Alan H. Schulman 2003. All rights reserved.