Matt Johnson

advertisement

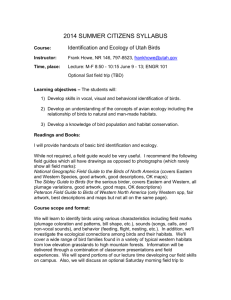

1 Matt Johnson Lecture Notes ORNITHOLOGY (Humboldt State Univ. WILDLIFE 365) LECTURE 1 - INTRODUCTION For January 23, 2001 I. Introduction A. Welcome to Ornithology. This course is labeled Wildlife 365 and meets here every T and R in this room, Wildlife 258, from 11 to 12. If that doesn't ring a bell, I suggest you get up and slide outa here right -- no hard feelings. B. OK, here we are. My name is Dr. Matt Johnson, and I'll be teaching both the lecture and lab sections of this course this semester. Is there anyone who didn't get a syllabus as they walked in? -- HAND THEM OUT C. Let's take a minute to go over the syllabus, D. Goals -- see syllabus OVERHEAD 1. Grading - see syllabus 2. Reading a. The reading for this class will be primarily out of Frank Gill's text, Ornithology. This third edition is a very good text book, and is overwhelmingly the first choice among university ornithology classes; we won't be using much in the way of supplementary literature. Gill is currently the science director for Nat'l Audubon Society, so he's a big-wig. b. You'll also need a field guide, as identification is a major part of the lab portion of this course. The three to choose from are the Nat'l Geographic guide, Peterson's Guide to Western Birds, and the new sibley guide. Peterson's has the advantages of grouping similar species together and only including western species, so you don't have to wade through a bunch of eastern stuff when you're thumbing through the guide looking for "your bird." However, these characteristics are also disadvantageous in that it means that the species are not listed in their phylogenetic order, (when they are, it can help you learn the order), and as a reference book, Peterson's is limited in that it only has the western species. The Nat'l Geo is a relatively new edition, and they've cleaned up some of the mistakes from earlier editions. It has the advantage of having the maps right next to the species illustrations. The new Sibley guide has the advantage and disadvantage of having TONS of information (too much sometimes). It will likely be the definitive field guide of the next few years. So to sum up I'd say Peterson's might be a bit better for ID'ing local birds, but the Geo or Sibley will serve you better in the long run, especially if you plan to pursue ornithology in other locations. It's your call. c. The final point regarding the readings is that this class will be fairly challenging, but I can promise that it will be much easier if you read the material before class. Really. 3. Lab 2 a. regular labs – see syllabus i. some in lab, some in field ii. all held regardless of weather b. the research paper – see syllabus 4. Lecture and Lab schedule – see syllabus OK....let's talk about BIRDS!!! II. Intro to Ornithology A. Birds are fascinating. There's no getting around it. Watch people at the park, at the wharf, on the trail -- most of them at least glance toward birds and watch them, others are certifiably obsessed with them, rattling off bird lists in otherwise polite conversations. A few of you may join the illustrious ranks of the avianly-obsessed after this course is over. Then again, some of you may look at birds only to swear at them after this course, but if that's the case, I ask you to swear at me and not the birds because birds are amazing creatures, worthy of are highest admiration. B. Birds aren't just fascinating right now either; they've been fascinating to people, including scientists (are they people too?), for centuries. Interestingly, many of the biggest break-throughs in biology have come from studying birds. Konoshi et al. summarized the contributions of birds to science in 1989: 1. Evolution, ecology, and sociobiology a. speciation -- allopatric, sympatric, and parapatric modes of speciation derived largely from avian examples, in fact natural selection itself was initially seeded (no-pun-intended) in part from Darwin's Finches on the Galapagos Islands. b. Heritability -- phenotype (outward manifestation of the individual) is a product of genotype (genetic make-up) and environmental influence (learned by studying natural selection in D's finches). c. Molecular analyses of phylogeny -- the process of studying the evolutionary relationships of species (i.e., their phylogeny) using molecular techniques has seen great advances through work on birds (e.g., DNA-DNA hybridization). Sibley and Allquist have been at the forefront of this work. Course this means they keep changing their minds as to who is related to whom, and field guides have to be revised every other year. What the ?*%& is a Flamingo? - a stork like duck or a duck-like stork? 2. Population and community ecology a. competition theory -- David Lack, Robert MacArthur, Evelyn Hutchinson; these guys were founding fathers of modern ecology, including its emphasis on species interactions like competition. They all studied birds. b. Island-biogeography -- the theory of island biogeography by MacArthur and Wilson has profoundly shaped a whole new field of biogeography, which includes theories on how to best design nature reserves. The backbone of this theory was comprised of analyses of the number of species of birds on Caribbean islands. 3. Behavioral ecology 3 a. Territoriality -- most of the major theoretical advances in the idea of territoriality came from Ornithologists, Fretwell, Lucas, Brown, Nice, etc. b. Mating systems -- many studies of individually marked birds (colorbanded birds) added to our understanding of the myriad ways species reproduce: monogamy, polygamy, leks, etc. Then molecular data from birds destroyed much of this. Monogamy is not as monogamous as it sometimes looks. c. Altruism -- cooperation in birds (Acorn woodpeckers, Florida scrub jays) led to some major advances in understanding altruism as influenced by the concept of kin selection. Individuals help others in proportion to how closely they are related. 4. Animal communication a. Nature vs. nurture -- ornithologists and ethologists (Konrad Lorenz) have studied bird communication and how it is influenced by heredity and the environment. 5. Orientation and navigation a. Many species migrate, but studies on birds have proven to be some of the most insightful in understanding what determines the onset of migration, how species navigate, and how they prepare physiologically for their arduous journeys. [check weidensaul for stats] C. OK, so birds are fascinating and have contributed to science. But why? What makes birds, perhaps more so than other wildlife, so fascinating and influential? SLIDES 1. Beauty a. There are about 9700 species world-wide, about twice as many as mammals; and scientists keep finding new ones every year (how long will that continue?). They range in size from the tiny (such as Costa's Hummingbird, about as long as an average pinky) -- to the very large (emu). This bird belongs to a group of flightless birds called Ratites; we'll learn about how they evolved, why they don't fly, and how they came to be distributed throughout the southern hemisphere but not the North in a few lectures. b. Birds also contain some of most brightly colored animals on earth. Consider: [e.g., aracari, western tanager]. Now think about mammals. I've got nothing against mammals, but with very few exceptions, the mammalian color scheme ranges from gray to brown to black to brownish-gray to blackish-brown to grayish-brownish-black......you get the picture. c. But birds' beauty goes beyond visual beauty. Bird songs inspire poetry, always have, let's hope they always will. Here are some examples (tape): i. Common Loon ii. Musician Wren iii. Winter wren iv. Olive sided Flycatcher v. Swainson's thrush 2. Observability a. mostly diurnal, often gather in groups (harlequin ducks), of course there are exceptions (secretary bird) b. vocal, easy to do audio surveys (pt count slide) c. territorial, usually fairly easy to relocate, if they are there (wandermap slide) 4 d. sexually dimorphic - sexes can be differentiated easily in the field for many species, you don't have to capture them and "turn them over" e. they build discrete nests making it possible to measure the reproductive output of individuals, something that is impossible in many species (think frogs). 3. The ease with which they can be studied in the field a. Relatively easy to catch (mist net) b. legs make great band holders -- perfect for studies in which individual birds need to be recognized (overnbird's legs), then banded individuals can be observed in the field (white-crowned sparrows). c. Many of them have relatively short life spans and generation, moderate rates of reproduction (makes population studies easier) - Dunnock nest d. Usually many species co-exist in a given habitat, making community-level ecological studies possible (multispecies shorebird flock) e. Many have conspicuous evolutionary curiosities, especially with regard to sexual selection -- useful for studying the processes of evolution (pin tailed whydah) f. Many can be kept in captivity fairly easily, making in lab studies of flight dynamics, digestion rates, behavior, etc. possible (Aratinga in cage) g. But others, thank goodness, cannot be kept in captivity very easily, so they remain unmolested, flying free so we may watch, remark, and wonder. (Frigate birds) [I know it's first day Matt, but try to this part slowly] 4. Poetry -- White-tailed tropicbird. "Birds are holes in heaven through which we may pass." (quote of the day, Walter Inglis Anderson). This bird embodies avian grace, avian beauty, and avian strength in wondrous flight.