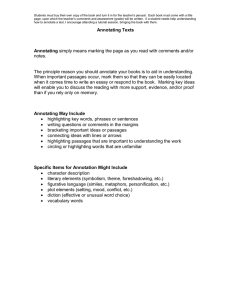

Annotating Texts

advertisement

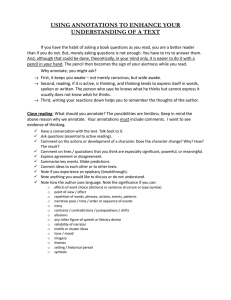

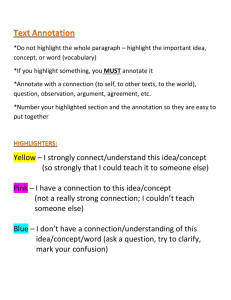

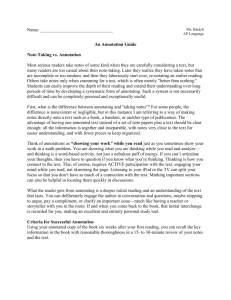

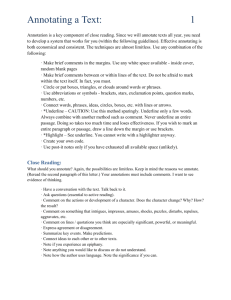

Annotating Texts Annotate: trans. To add notes to, furnish with notes; intr. To add or make notes What does it mean to annotate a text? Many editors and authors publish annotated editions of texts, which often include notes on historical background, definitions of key terms, and critical discourse. Critical readers, though, usually strive to be active readers by filling the text with their own notes. Why Annotate? Annotating/Marking up texts often increases the reader’s ability to remember key concepts, themes, diction, and imagery through forming an active, rather than a passive, relationship with the text. Annotating also allows the reader to recall where certain information is located within the text. If you know you marked that important passage at the top/bottom/middle of the page, finding the passage will be much easier than if no passages have been marked at all. Ways to Annotate: Highlighter – identify key sections without actually interfering with the text Pencil – Underline, circle, star key ideas, write questions and comments in the margins. Pencil marks can usually be easily erased or changed. Index – Create a personal index in the front or back of the text which identifies where key words or ideas appear in the text External Markers (ex. Post-it Flags) – allow for annotating without damaging the text (ideal for texts such as library books) What to annotate: Running themes Repeated images/symbols/diction/ideas Confusing passages/passages that spark questions Shifts in tone/form Words to define Anything you, as the reader, find interesting Passages/ideas that might relate to other texts Of course, what you choose to annotate will vary depending on what you are attempting to glean from the text. If, for example, you are trying to determine which rhetorical strategies the author employs (logos, pathos, ethos), you would mark examples of those strategies. On the other hand, if you were trying to determine the steps in a procedure, you might number those steps as they appear.