The Effects of Adding a Work Component to the Transition Program

advertisement

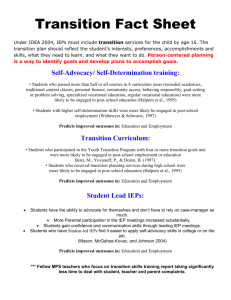

The Effects of Adding a Work Component to the Transition Program on Rates of Competitive Employment for Disabled Students at Roosevelt High School. Siiri Rimpila SCG 410 Dr. Anthony E. Epah Summer I, 2003 2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE Introduction An important aspect of high school is to prepare students for work. Benz, Yovanoff & Doren (1997) cited the School-to-Work Opportunities Act (STWOA) of 1994 as establishing a set of guidelines for schools to form transition programs to better prepare students for work and possible further education. The STWOA recommends work-related learning opportunities in both the school and at work settings. Bove, McNeil, Paolucci-Whitcomb, & Nevin (1991) found that many special education students are not leading integrated and independent lives after they leave high school (as cited in Love & Malian, 1997.) One theme to consider is that disabled adults have comparatively low job placement rates. Transition programs have been formulated to increase rates of job placement for disabled students. The components of these transition programs will be further explored in this paper. An important factor of the transition period is cultivating decision-making skills through the various experiences that are offered to the student. Unfortunately, not all students benefit equally from these programs. Finally, a review of the independent and dependent variables of the study will be given. Job Rates People with disabilities are not represented equally in the workforce. Marder & D’Amico (1992) found that only about 33% of students with disabilities are able to find 3 substantial work within the first year after graduation as compared to an estimated 67% of non-disabled graduates, (as cited in Benz, Yovanoff & Doren, 1997.) In addition, disabled adults are not only underemployed, but also earning very low wages (Haring, Lovett & Smith, 1990, as cited in Collet-Klingenberg, 1998; Affleck, Edgar, Levine, & Kottering, 1990, as cited in Blalock & Patton, 1996.) Transition programs help to decrease these discrepancies, but not all transition programs accomplish this goal. Transition programs need to be studied in order to reveal which components yield the most success in terms of post-high school job placement. Transition Program Components Many studies have been conducted to identify various components of high school transition programs. Benz, Yovanoff & Doren (1997) identified strong social skills and solid job search skills as increasing chances of competitive employment for both disabled and non-disabled students within one year after graduation. Collet-Klingenberg (1998) reported that transition teams with strong planning skills tend to have stronger transition programs and post-high school job outcomes. Knight and Aucoin (1999) indicated the importance of a strong team effort involving the workplace. In addition, selfdetermination skills, or self-advocacy skills have also been emphasized in various transition studies, yet not many teachers are incorporating these skills into their curriculum (Lindstrom & Benz, 2002; Thoma, Baker, & Saddler, 2002; ColletKlingenberg, 1998). Another important component of transition programs is the availability of on-the-job training and work experiences (Benz, Yovanoff & Doren, 1997; 4 Collet-Klingenberg, 1998; Heal & Rusch, 1995 as cited in Corbett, Clark, & Blank, 2002.) However, Heal and Rusch’s (1995) study found no correlation between careerrelated classes and employment rates (as cited in Corbett, Clark, & Blank, 2002.) Decision-making The above mentioned transition components allow students to become more knowledgeable and well-rounded about jobs. This exposure to the types of decisions a person will need to make after high school is another very important part of transition programs. Savickas (1999) reports that being aware of future decisions and what resources are available to make those decisions helps students in coping with the transition to adult life. Lindstrom and Benz (2002) also talked about the process of decision-making. They reported that this process should be self-directed and gradual. In addition, Lindstrom and Benz (2002) report that the process of elimination can help learning disabled students find a better job match. Having a work opportunity and curriculum designed to increase job awareness gives students more resources to help them in their career decision-making after graduation. Transition Success Rates Unfortunately, not all students benefit equally from the school to work programs in high schools. Benz, Yovanoff & Doren (1997) identified disabled women as “five times less likely to be competitively employed one year out of school than were all other groups” (p. 157.) In addition, they found that minority students and students taking care of young children were three times less engaged in some form of productive activity than 5 non-minority students and students with no parenting responsibilities. Bounds (1997) and Halloran & Johnson (1992) have found that nearly 62% of students that had some form of work experience while in high school were able to remain in competitive jobs after high school. Only about 45% of students with no high school work experience maintained competitive employment (as cited in Knight & Aucoin, 1999). These discrepancies need to be further explored so that all special education students can benefit equally from the programs that are provided for them. Independent Variable The independent variable of the study will be a work experience program. Special education seniors at Roosevelt High School will all continue to participate in the existing transition program. One group will also participate in a work component and a second group will not. Many studies have indicated that work opportunities in high school are important in helping students to transition into the working world (Lindstrom & Benz, 2002; Collet-Klingenberg, 1998.) The study will examine how adding a strong work component to a current transition program affects the rate of competitive employment among disabled students. Roosevelt High School currently does not have a work component as part of its transition program. Roosevelt has been selected so that the addition of a work component can be isolated and measured. Dependent Variable The dependent variable of the study will be the level of job readiness and rates of competitive employment. Sampson, Peterson, Reardon, & Lenz (2000) report that 6 readiness assessments can be used to determine the success of career programming interventions. Job readiness will be measured through a job readiness inventory given as a pretest and a posttest to both groups. Group scores will reveal how much improvement students have made in terms of job readiness, as well as if the addition of a work component increased student levels of job readiness. Post high school employment outcomes for each group will also be tallied. The students will be called one year after graduation to determine how many from the control group (transition program only) and the experimental group (transition program plus work experience) are actually working 15 or more hours per week. Based on current research, the hypothesis is that students participating in the experimental group, in which a work component is added, will have higher rates of competitive employment one year after they graduate high school. Conclusion In conclusion, there are many factors that contribute to increasing the rates of employment for disabled students after they graduate high school. It is important to finetune transition programs since there are so many disabled adults who are either unemployed or underemployed and underpaid. Many studies have identified important emphases in transition programs. A work component has been highlighted in a number of these studies as being an invaluable opportunity. So far, no study has isolated the variable of a work component within high schools to account for confounding factors (such as number of job available to young adults in that region, etc.) This study seeks to better 7 understand what effects the addition of a work component has on rates of competitive employment for disabled high school students at Roosevelt High School. Further studies at larger schools would be recommended in the future. 8 REFERENCES Benz, M. R., Yovanoff, P. &, Doren, B. (1997). “School-to-Work Components that Predict Post School Success for Students with and without Disabilities.” Exceptional Children, 63, 151-164. Blalock, G., & Patton, J. R. (1996). “Transition and Students with Learning Disabilities.” Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29, 7-17. Collet-Klingenberg, L. L. (1998). “The Reality of Best Practices in Transition: A Case Study.” Exceptional Children, 65, 67-79. Corbett, W. P., Clark, H. B., & Blank, W. (2002). “Employment and Social Outcomes Associated with Vocational Programming for Youths with Emotional or Behavioral Disorders.” Behavioral Disorders, 27, 358-374. Lindstrom, L. E. & Benz, M. R. (2002). Phases of Career Development: Case Studies of Young Women with Learning Disabilities.” Exceptional Children, 69, 67-83. Love, L. L., & Malian, I. M. (1997). “What Happens to Students Leaving Secondary Special Education Services in Arizona?” Remedial & Special Education, 18, 261-270. Knight, D. & Aucoin, L. (1999). “Assessing Job-Readiness Skills: How Students, Teachers and Employers can Work Together to Enhance On-the-Job Training.” Teaching Exceptional Children, 31, 10-19. Savickas, M. L. (1999) “The Transition from School to Work: a Development Perspective.” The Career Development Quarterly, 47, 326-336. Sampson, J. P. Jr., Peterson, G. W., Reardon, R. C., & Lenz, J. G. (2000) “Using Readiness Assessment to Improve Career Services: A Cognitive Approach.” The Career Development Quarterly, 49, 146-174. Thoma, C. A., Baker, S. R., & Saddler, S. J. (2002). “Self-Determination in Teacher Education.” Remedial and Special Education, 23, 82-89.