CONSTRUCTIVE CONFLICT STRATEGIES

advertisement

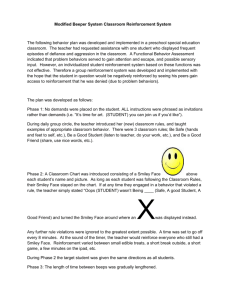

Constructive Interparental Running head: CONSTRUCTIVE CONFLICT STRATEGIES Constructive Interparental Conflict Strategies as a Predictor of Adolescent Aggression and Conflict Julie Ann Gdula University of Virginia Distinguished Major Thesis Advisor: Joseph P. Allen Second Reader: Robert E. Emery 1 Constructive Interparental Abstract This study examined the relationship between father’s positive reasoning during conflicts with mother and several adolescent outcomes, including aggressive attitudes and conflict strategies with peers and romantic partners. Participants included a diverse community sample of 126 adolescents and their mothers, peers, and romantic partners in a multimethod, multiple reporter, longitudinal study. Results revealed that father’s positive reasoning with mother at teen age 13 predicted lower adolescent attitudes toward aggression and less antagonistic conflict with a romantic partner at teen age 17 in the long term. Father’s positive reasoning predicted adolescent attitudes toward aggression through a relationship partially mediated by adolescent autonomous relatedness with peers at age 14 and adolescent aggression at age 15. Findings are interpreted as suggesting pathways by which parents may shape their adolescents’ beliefs and behaviors through modeling and socialization, and the need for further research in positive psychology is discussed. 2 Constructive Interparental 3 Constructive Interparental Conflict Strategies as a Predictor of Adolescent Aggression and Conflict There is little dispute within the field of psychology that interparental abuse and negative conflict style, such as verbal and physical aggression, have adverse consequences for children and adolescents. Interparental conflict has long been known to have effects on both the cognitive and social development of children (Wierson, Forehand, & McCombs 1988). Consistent conflict between parents has been linked to several negative outcomes in children, such as delinquency and increased aggression in peer relationships (Davies & Cummings, 1994). Research shows that adolescents who witness violence between their parents are more likely to engage in aggressive acts (Moretti, Obsuth, & Odgers 2006), and boys exposed to aggressive interparental conflict are more likely to judge aggression as acceptable within romantic relationships (Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004). Though aggressive conflict has been consistently predictive of negative outcomes for teens, some studies suggest that different types of conflict styles lead to very different outcomes in adolescence. For example, a hostile argument style between parents is more closely linked with teen problem behaviors than the frequency of argument (Buehler, Krishnakumar, & Stone 1998). Although no relationship is without conflict, these findings suggest that what matters is not that an argument occurred, but how it is handled by the parents (Du Rocher Schudlich & Cummings 2003). How are researchers to decide which conflict styles are most predictive of positive outcomes for adolescents? To date, most researchers have focused on children and their immediate emotional responses to conflict to answer this question. Grych and Fincham’s (1990) cognitive-contextual framework presents an interdependent model of several variables which refer to the actual argument, context elements pertaining to the child’s mood and environment, and the child’s emotional and coping behaviors in response. Subsequent research has found support for this model for internalizing problems, but not for externalizing problems, suggesting that further research is necessary to determine a framework for understanding such problems as aggression and delinquency (Dadds, Atkinson, Turner, Blums, & Lendich, 1999). Based on the apparent importance of children’s perception of their parents’ arguments, Grych, Seid, & Fincham (1992) developed a questionnaire to determine children’s perspectives on conflict, called the Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC). Following in this vein, Davies & Cummings (1994) propose an emotional security hypothesis which has driven most further study in the field. It characterizes different interparental conflict tactics by the children’s beliefs about the future stability of their parents’ relationship, or emotional security. In one study based on this theory, if children felt threatened by arguments, they were more likely to exhibit both internalizing and externalizing symptoms one year later (Harold, Shelton, & GoekeMorey 2004). Using the emotional security hypothesis, Goeke-Morey, Cummings, & Harold (2003) classified parental conflict tactics as either constructive or destructive, according to children’s immediate emotional responses to video representations of strangers in a hypothetical argument situation. Emotional responding produced equivocal results for calm discussion, problem solving, and support. Notably, this study used actors, and not the children’s real parents, to elicit emotions. Thus the emotions were only related to one controlled episode involving people with whom the child had no real relationship. Few methods and theories other than measurement or observation of children’s emotions have been used in classifying parental conflict styles and their effects on children. Katz & Constructive Interparental 4 Gottman (1993) made observations of parents’ conflicts and then assessed children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors three years later. Though the results indicate that different conflict styles do contribute to different outcomes in the children, both patterns studied included hostile, angry, and withdrawn behavior from the parents. Another study used a stress and coping model to explain children’s reactions to parental conflict (Cummings 1998). According to this model, children’s distress leads them to become sensitized to anger, making them incapable of effectively coping with angry situations in the future. Though the author acknowledges a difference between destructive and constructive tactics, he does not provide much detail about the latter. To date, little research has been done on the effects of constructive conflict tactics. Cummings & Davies (2002) purport the need for a process-oriented approach to the effects of marital conflict on children; this requires a deeper exploration of interparental conflict tactics as protective factors, and the effects on children and adolescents over a longer period of time. Though the long-term implications of constructive conflict tactics have yet to be examined, Cummings, Goeke-Morey, and Papp (2004) found that in the short term, destructive tactics increased aggression while constructive tactics decreased it. This aggression led to delinquent conduct problems later in adolescence, which suggests that constructive interparental conflict tactics may well serve as a protective factor for teens. In addition to conduct problems, aggression in adolescence has been correlated with a series of physical and emotional problems, including cardiovascular disease, internalizing and externalizing behaviors, lowered social status, and negative academic achievement (Smith & Furlong 1994). Adolescents’ attitudes toward aggression have also been identified as a risk factor for violence in romantic relationships (Rickert, Vaughan, & Wiemann 2002). Due to these serious correlates of adolescent aggression, identifying how constructive interparental conflict may serve to protect adolescents against later aggression is crucial. Even before they begin dating, aggression may adversely affect adolescents through their peer relationships. Aggression has been closely linked with peer rejection (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt 1990), and the literature suggests that parents play a major role in the development of adolescent aggressive behavior and attitudes. Studies indicate that parents’ aggression and conflict styles play a significant role in the establishment of their children’s friendships, within both the interparental relationship and the parent-child relationship. Mother and father aggression in general predicted less peer intimacy and poor social skills in adolescence, with the effect of father aggression evident only in later adolescence (Schlatter, 2001). Overtly aggressive children tend to have parents who exhibit more conflict and aggression within their relationship (Grotpeter, 1998). The parent-child relationship also appears to be a mechanism by which parental aggression influences friendships; adolescents aggressed by their parents are less popular, less well-liked, and described as more externalizing in behavior by their peers, and adolescent victims of physical abuse are more likely to inflict such abuse on peers (Tencer, 2005; Wolfe, Scott, Wekerle, & Pittman, 2001). The serious potential impact of parents on their children in the form of peer relationships requires attention, as it will likely predict future social skills and the success of romantic relationships. Research indicates that adolescent peer relationships correlate with romantic relationships later on. For example, Feiring, Deblinger, Hoch-Espada, & Haworth (2002) found that girls with less secure friendships were more likely to exhibit aggression toward romantic partners. However, as in parental relationships, conflict is an unavoidable and even necessary part of adolescent romantic relationships. One study found that conflict is particularly characteristic of Constructive Interparental 5 various types of adolescent relationships and may even serve a developmental purpose as adolescents learn to compromise with others while maintaining autonomy (Laursen 1995). However, as in parental relationships, it is the way conflict is handled that matters most, and there is considerable evidence that teens learn how to do this from their parents. Adolescents who observed aggression between their mothers and fathers reported higher levels of aggression toward their own romantic partners (Moretti, Obsuth, & Odgers 2006), which indicates an indirect, observational relationship between the conflict styles of the parents and the adolescents. Reese-Weber and Bartle-Haring (1998) found this same indirect relationship between the adolescent’s parents’ conflict style and the adolescent’s style with a romantic partner. In addition, they also found a direct relationship; rather than just observing their parents and learning from them how to interact with a romantic partner, adolescents usually used the same conflict style with a romantic partner as they used in conflicts with their parents. This suggests that adolescents learn from their parents both by observing them and by interacting with them. Martin (1990) also suggests that teens learn how to act in their dating relationships based on the specific quality of their relationships with their parents. One study found that less securely attached adolescents demonstrated a more negative affect, less confidence, and a more maladaptive conflict style in arguments with romantic partners (Creasey & Hesson-McInnis, 2001). Thus it seems that both modeling or socialization and attachment theory serve as mechanisms by which interparental conflict tactics lead to the development of children’s conflict styles and aggressive behavior in romantic relationships. Several of the aforementioned studies revealed different results for boys than for girls. For example, while some studies have found that children of aggressive parents will also display aggression regardless of gender (Crick 1996, Mizokawa 2000), others only find results for boys (Kinsfogel & Grych 2004). The difference lies in the fact that girls use more relational aggression than overt aggression, meaning that girls are more likely to spread rumors or deliberately make others jealous than they are to use physical force or act openly hostile. When aggression is operationalized to include relational aggression, a study will usually show similar levels of aggression in boys and girls. In relationships, however, boys are more likely than girls to endorse aggression toward a partner (Fering, Deblinger, Hoch-Espada, & Haworth, 2002). In adolescence, gender seems to play a role in differentially affecting results of studies on aggression. Gender may also play a role for parents of adolescents. Most child and adolescent research has focused on mothers, and fathers have been largely ignored; however, recent research suggests that fathers become increasingly important in adolescence, and their impact should not be overlooked. Kempton, Thomas, and Forehand (1989) found that fathers’ aggressive conflict tactics were influential in adolescent functioning, but mothers’ were not. Allen, Hauser, and Bell (1994) found a correlation between fathers’ displays of autonomy and relatedness toward their adolescents and the adolescents’ psychosocial development. Research also indicates that fathers’ psychopathology is related to adolescent psychopathology (Phares and Compas, 1992). Though the reason for the increasingly important role of the father as his child enters adolescence is unclear, some researchers posit that the father is the parent who mediates a child’s transition into adulthood and the larger community outside the family. Consistent with this, one study finds that mothers are more family-oriented than fathers or adolescents (Jurich, Schumm, & Bollman 1987); this suggests that mothers may serve as more accurate reporters of conflict tactics between family members. Constructive Interparental 6 Previous studies have provided a solid empirical foundation for the questions investigated in the present study, but none have examined the long-term effects of constructive marital conflict style on adolescent aggression and conflict in peer and dating relationships. The present study evaluates change over a span of five years – from early to late adolescence. Instead of evaluating the emotions of participants immediately after viewing a video in a controlled setting, the current study focuses on general behaviors and attitudes and their relationship to real parents’ conflict styles. To eliminate social desirability effects and reporter bias, the study employs a multi-informant design, combining information from adolescents, their mothers, their peers, and their romantic partners. In the current study, we predict that fathers’ positive reasoning in arguments with mothers will be associated with a lower level of teen aggression by late adolescence. We also hypothesize that it will predict improvements in the quality of the teen’s future peer and romantic relationships. We propose that positive reasoning in interparental conflicts will function as a protective factor against the adolescent’s development of less effective conflict strategies, such as the endorsement of aggressive conflict tactics and maladaptive behavior in arguments with peers and romantic partners. Method Participants This report is drawn from a larger longitudinal investigation of adolescent social development in familial and peer contexts. Participants included 126 seventh and eighth graders (52 boys and 74 girls) and their mothers. Participants returned for subsequent annual visits with their peers and romantic partners. Adolescents completed initial interviews at approximately age 13 (M=13.3, SD =.61) and were then reinterviewed annually for the next six years. The sample was racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse: 67 % identified themselves as Caucasian, 21% as African American, and 12 % as mixed race or other. Adolescents’ parents reported a median family income in the $30,000 –$39,999 range. At each wave, adolescents’ were also asked to nominate their “closest friend” of the same gender to be included in the study. Close friends were defined as “people you know well, spend time with and who you talk to about things that happen in your life.” For adolescents who had difficulty naming close friends, it was explained that naming their “closest” friends did not mean that they were necessarily very close to these friends, just that they were close to these friends relative to other acquaintances they might have. Adolescents were recruited from the 7th and 8th grades at a public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the southeastern United States. An initial mailing to parents of students in the relevant grades in the school gave them the opportunity to opt out of any further contact with the study. Only 2% of parents opted out of such contact. Of all families subsequently contacted by phone, 63% agreed to participate and had an adolescent who was able to come in with both a parent and a close friend. This sample appeared generally comparable to the overall population of the school in terms of racial/ethnic composition (37% non-White in sample vs. approximately 40% non-White in school) and socioeconomic status (mean household income =$44,900 in sample vs. $48,000 for community at large). The adolescents provided informed assent, and their parents provided informed consent before each interview session. The same assent/consent procedures were also used for collateral peers and their parents. Interviews took place in private offices within a university academic building. At the first wave of data collection, adolescents came in for two visits, the first with their parents, and the second Constructive Interparental 7 with their identified closest friend. Approximately 1 year later, adolescents again came in for two visits, the first alone and the second with the person who they named as their current closest friend in the wave 2 individual interview. Parents, adolescents, and peers were all paid for their participation. Of the original 184 participants, 126 of them had father figures about whom their mothers completed questionnaires in wave 1. This sample differs significantly from the subsample of participants without father figures, in gender and income. Boys comprise 58.6% of participants without father figures but only 41.3% of participants with father figures. The median family income of participants without father figures was in the $15,000-19,999 range, while the median family income for participants with father figures was in the $30,000 –$39,999 range. The sample that participated in both waves 1 and 2 of the study was a subsample of 112 adolescents who had complete data at Wave 1. Adolescents reported knowing their close friends for a mean of 4.73 years. Attrition analyses revealed no significant differences between the 112 adolescents who did versus the 14 adolescents who did not return for the second wave of the study on any of the demographic or substantive measures in the study. In addition to selecting close friends, adolescents had the option to select romantic partners as well, starting with the fifth wave of the study. To qualify, partners must have been dating for at least two months at the time of the visit. The sample that both participated in wave 1 of the study and selected a romantic partner was 49. Attrition analyses revealed no significant differences between the 49 adolescents who did versus the 77 adolescents who did not select romantic partners on any of the demographic or substantive measures in the study. The subsample of participants with complete data at wave 6 of the study included 95 of the original 126 participants. Attrition analyses revealed no significant differences between this subsample and the original subsample. Measures Father’s positive conflict tactics with mother. Mothers reported on their partners’ use of constructive conflict tactics during interparental arguments using the 3-item positive reasoning subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). Using a 7-point Likert scale (“never” =1 to “more than 20 times” = 7), mothers rated how often their partners exhibited certain positive argument behaviors over their lifetimes. The items include calm discussion, backing up arguments with information, and bringing in a mediator to help solve problems. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale is .46, which is reasonable given that the measure intends to assess a wide variety of positive reasoning tactics with only three items. Adolescent autonomy/relatedness toward peers. Teens and their close peers participated in an interaction task during which they chose patients who they believed should receive a cure for a fatal disease. After making their decisions separately, teens participated in an eight-minute, videotaped interaction task during which they came to an agreement about which 7 of the 12 patients most deserve the treatment, as well as which 3 are the most deserving among them. The Constructive Interparental 8 adolescent’s autonomy and relatedness were assessed using the Autonomy and Relatedness Coding System (Allen, Hauser, Bell, McElhaney, Tate, Insabella, & Schlatter, 2000). Teens were assessed on their Positive Peer AR, which combines their scores for both positive autonomy and positive relatedness. Codes for autonomy were based on the adolescent’s reasoning abilities and confidence during arguments, and relatedness codes depended on levels of collaboration and warmth/ engagement during the task. Intraclass reliability for this measure was .71. Aggressive behaviors. Close peers used a 4-point scale (ranging from 1 to 4) modeled after the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988) to report on various aggressive behaviors that the target teens engaged in. Items include topics in both physical and relational aggression, such as bullying and gossiping. Cronbach’s alpha for this 7-item Aggression subscale was .77 which indicates high internal consistency. Aggressive attitudes. Adolescents rated their own attitudes toward aggression using the Adolescent Attitude Questionnaire (Guerra, 1986; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). This 18item scale measures adolescents’ beliefs about the role of aggression in increasing their self esteem or improving their self image, as well as its legitimacy in certain situations, using a 5-point rating scale (“really disagree”=1 to “really agree”=5). Cronbach’s alpha for this measure is .89, which indicates high internal consistency. Romantic relationship antagonistic conflict. Romantic partners rated levels of conflict and antagonism in their relationship using the Conflict and Antagonism subscales of the Network of Relationships Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985; Furman, 1996). Each subscale contains 3 items on a 5-point Likert scale (1= “little or none” to 5= “the most”). The Conflict scale includes questions relating to how much the partners fight or disagree with each other, and the Antagonism subscale relates to how much the partners nag or are annoyed with each other and how much they get on each other’s nerves. Because the scales assessed similar constructs and behaved very similarly in our data, we merged them to measure Antagonistic Conflict. Cronbach’s alpha for our new 6-item subscale was .81. Results Preliminary Analyses Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for all measures used in the study. Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations Measure and Subscale Conflict Tactics Scale Father's positive reasoning with mother Father's physical aggression toward mother Mean Teen Age M SD 13 7.57 1.63 13 11.78 1.72 Constructive Interparental Peer Interaction Task Overall Positive Autonomy and Relatedness Harter, Close peer report Teen aggression Network of Relationships Inventory Antagonistic conflict Adolescent Attitude Questionnaire Overall attitudes toward aggression 14 2.34 0.52 15 22.41 3.73 17 0 0.92 18 29.33 9.33 9 An initial analysis of the effects of participant gender on the relationship between father’s positive reasoning with mother and adolescent outcomes revealed that gender was statistically significant in the case of both teen attitudes toward aggression and peer report of teen aggression (see table 2). Other moderating effects of gender are reported where relevant below. Analyses revealed no statistically significant effects of income at the p < .05 level for the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and any of the adolescent outcomes studied. Table 2 presents simple correlations among the primary constructs examined in the study. Table 2. Correlations Among Primary Constructs 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. -.29** .24* .26** -.42** -.33*** -.07 .21* -- -.24* -.12 .49*** -.11 .09 .21* -- -- .30*** -.04 -.35*** -.02 .19* -- -- -- -.14 -.24* .12 .17* -- -- -- -- .003 .14 -.31** -- -- -- -- -- -.23** -.07 -- -- -- -- -- -- -.11 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 1. Father’s positive reasoning 2. Father’s physical aggression 3. Positive Peer AR 4. Teen aggression 5. Antagonistic conflict 6. Attitudes toward aggression 7. Gender 8. Income Note: *** p ≤ .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05 Long term results Constructive Interparental 10 We examined whether father’s positive reasoning at teen age 13 would relate to teen’s attitudes toward aggression in later adolescence using a hierarchical regression model. Results indicated a negative relationship between positive reasoning and attitudes toward aggression (see table 3). This means that teens whose fathers used more positive reasoning tactics in arguments with their mothers were less likely to endorse aggression in their own interactions with others. Table 3. Predicting Changes in Teen Attitudes Toward Aggression from Father’s Positive Reasoning. β β entry final Total R2 R2 Step I. Gender Income Step II. Father’s Positive Reasoning with Mother Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. -.29** -.17 -.31** -.11 -.35*** -.35*** * p < .05. N = 95 .10* .11 *** .21 *** We also examined whether father’s positive reasoning at teen age 13 would relate to teen’s romantic relationships in later adolescence, using a hierarchical regression model. Results indicated a negative relationship between father’s positive reasoning and teen relationship conflict and antagonism (see table 4). This means that teens whose fathers used more positive reasoning in arguments with their mothers were less likely to be in romantic relationships characterized by nagging and conflict, according to their romantic partners. Table 4. Predicting Antagonistic Conflict in Romantic Relationships from Father’s Positive Reasoning β β entry final Total R2 R2 Step I. Gender .14 .21 Income -.31* .13 .12* Step II. Father’s positive reasoning with -.42** -.42** .16** .28** Mother Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. N = 49 Intervening variables Next we examined other mid-adolescence variables predicted by father’s positive reasoning, using a hierarchical regression model. The first of these variables is teen positive autonomy and relatedness at age 14 as observed in an interaction task with a close peer. Results indicated a positive relationship between father’s positive reasoning and teen positive autonomy and relatedness (see table 5). This means that teens whose fathers used more positive reasoning in arguments with their mothers were more likely to be confident and to reason effectively, and to collaborate with their peer and be more engaged in the task. Constructive Interparental 11 Table 5. Predicting Positive Autonomy and Relatedness from Father’s Positive Reasoning β β entry final Total R2 R2 Step I. Gender .10 .10 Income .22* .28 Step II. Father’s Positive Reasoning with Mother .20* .20* Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. N = 112 .05 .04* .09* The second mid-adolescence variable we examined is teen aggression at age 15 as reported by close peer. Results indicated a negative relationship between father’s positive reasoning and teen aggression (see table 6). This means that teens whose fathers used more positive reasoning in arguments with their mothers were less likely to be perceived as aggressive by their closest friends. Table 6. Predicting Teen Aggression from Father’s Positive Reasoning β β entry final R2 Step I. Gender Income .21* .14 .23* .08 Step II. Father’s Positive Reasoning with Mother .26** .30** Step III. Gender * Father’s Positive Reasoning -.25** -.25** Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. N = 99 Total R2 .05 .06** .11** .07** .18*** There was a statistically significant gender interaction between father’s positive reasoning and close peer report of teen aggression. Analyses revealed a greater difference in aggression for boys than for girls as a function of father’s positive reasoning (see figure 1). Figure 1 Constructive Interparental 12 Gender Interaction for Teen Aggression at Age 15 as a Function of Father’s Positive Reasoning at Age 13 0.4 0.2 Girls Teen Aggression 0 Boys -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 Low High Father's Positive Reasoning Intervening variables partially mediate long term effects Next we examined whether the long-term results were affected by any of the above intervening variables. We used mediation tests to determine whether these variables changed the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and teen attitudes toward aggression at age 17, or the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and romantic relationship conflict and antagonism. We found no mediating effects for romantic relationship conflict and antagonism. However, we did find two partially mediating effects on teen attitudes toward aggression at age 17, and a third mediating effect on another intervening variable, teen aggression at age 15. The first partial mediator we tested was teen positive autonomy and relatedness. When positive autonomy and relatedness at age 14 was included in the model measuring teen attitudes toward aggression at age 18, the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and aggression at age 18 decreased, although it still remained significant (see table 7). This means that while father’s positive reasoning still does predict teen attitudes toward aggression at age 17 on its own, it also predicts teen positive autonomy and relatedness at age 14, which in turn predicts teen attitudes toward aggression at age 17. Table 7. Positive Autonomy and Relatedness with Peer as a Partial Mediator of the Relationship between Father’s Positive Reasoning and Teen Attitudes Toward Aggression β β entry final Total R2 R2 Step I. Constructive Interparental 13 Gender -.23 -.21 .05 Income -.13 .01 Step II. Father’s positive reasoning with -.37*** -.32** .14*** .19*** Mother Step III. Positive Peer Autonomy and -.25* -.25* .05* .24*** Relatedness Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. N = 92 The next partial mediator we tested was teen aggression as reported by close peer at age 15. When teen aggression at age 15 was included in the model measuring teen attitudes toward aggression at age 18, the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and aggression at age 18 decreased, although it still remained significant (see table 8). This means that while father’s positive reasoning still does predict teen attitudes toward aggression at age 18 on its own, it also predicts teen aggression at age 15, which in turn predicts teen attitudes toward aggression at age 17. Table 8. Teen Aggression as a Partial Mediator of the Relationship between Father’s Positive Reasoning and Teen Attitudes Toward Aggression β β entry final Total R2 R2 Step I. Gender -.17 Income -.13 .04 Step II. Father’s positive reasoning with -.38*** -.34** .14*** .18** Mother Step III. Teen aggression as rated by close -.17 -.17 .02 .20** peer Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. N = 99 We also ran mediation tests on the relationships between father’s positive reasoning and the intervening variables. When positive autonomy and relatedness with peers at age 14 were included in the model measuring teen aggression at age 15, the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and aggression at age 15 decreased, although it still remained significant (see table 9). This means that while father’s positive reasoning still does predict teen aggression at age 15 on its own, it also predicts teen positive autonomy and relatedness at age 14, which in turn predicts teen aggression at age 15. These findings are consistent with a partial mediation of the predictive effect of father’s positive reasoning via teen positive autonomy and relatedness. Table 9. Positive Autonomy and Relatedness as a Partial Mediator of the Relationship Between Father’s positive Reasoning and Teen Aggression β β entry final Total R2 R2 Constructive Interparental 14 Step I. Gender .21* .20* Income .15 .07 Step II. Father’s positive reasoning with .26** .23** Mother Step III. Positive Autonomy and Relatedness .15 .15 Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. N = 99 .05 .14** .12** .02 .14** Over and Above Physical Aggression To examine whether positive reasoning predicted any variance that could not be more simply accounted for by paternal physical aggression, we included father’s physical aggression toward mother in analyses of our long-term results. In a hierarchical regression model predicting teen attitudes toward aggression at age 17, we found that father’s physical aggression was not significant (p= .392). This means that father’s physical aggression did not predict teen attitudes toward aggression in late adolescence above chance level. For this reason, we did not proceed to analyze father’s physical aggression in a model with father’s positive reasoning predicting teen attitudes toward aggression at age 17. In a hierarchical regression model predicting teen romantic relationship conflict and antagonism, we found that father’s physical aggression was significant (p= .002). We then added father’s positive reasoning to the model which was also significant and increased R2 to .35 (see table 10). This means that father’s positive reasoning predicts romantic relationship conflict and antagonism over and above father’s physical aggression. Table 10. Predicting Adolescent Antagonistic Conflict in Romantic Relationships from Father’s Positive Reasoning β β entry final Total R2 R2 Step I. Gender .14 .15 Income -.31* -.05 .12* Step II. Father’s physical aggression toward .46** .34* .13** .25** Mother Step III. Father’s positive reasoning with -.32* -.32* .10* .35** Mother Constructive Interparental 15 Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. N = 49 We did not include physical aggression in our analyses of the intervening variables, as in this study we were primarily concerned with the long-term outcome variables as noted above. Discussion As hypothesized, father’s positive reasoning in arguments with mother at teen age 13 was significantly correlated with more adaptive adolescent attitudes toward aggression at age 18. Further, father’s positive reasoning was predictive of less adolescent romantic relationship conflict at age 17. In addition to its main effects, the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and teen attitudes toward aggression was partially mediated by teen behaviors displaying autonomy and relatedness with peer and by peer ratings of teen aggression at mean teen ages 14 and 15, respectively. Father’s positive reasoning was a better predictor of the longterm outcomes than was father’s physical aggression toward mother. These results will each be explained in more detail below. The first long-term outcome studied was the relationship between father’s positive reasoning and teen attitudes toward aggression. Though there is little research to date on constructive conflict tactics, the available literature is consistent with more positive views about aggression for teens whose parents use these constructive tactics (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2004). One possible explanation for this is that teens who witness calm reasoning and discussion between their parents during arguments are more likely to model this same technique in their own conflicts. It is also possible that fathers who use constructive conflict tactics with their partners also use them with their adolescents, and that the adolescents learn through socialization. In the real world, a combination of both of these factors, modeling and socialization, is possible. From another perspective, teens whose fathers do not use positive reasoning with their mothers are more likely to endorse aggression in their own lives. It is possible that other, less constructive conflict tactics take the place of positive reasoning in interparental arguments and that teens are then socialized to use these tactics themselves. Another possible explanation supported by the current study’s results is that positive reasoning is a necessary skill that teens learn from their parents; teens who fail to develop this ability to handle arguments rationally develop maladaptive attitudes about the efficacy of aggression in conflict resolution. The next long-term outcome studied was the relationship between father’s positive reasoning with mother and antagonistic conflict in teen’s romantic relationship, according to teen’s romantic partner. Father’s positive reasoning negatively predicted romantic relationship antagonistic conflict. As with the above finding, this result suggests that teens may model their parents’ interactions for cues in handling conflicts with their own romantic partners. Teens whose fathers used positive reasoning may have used it with their own partners, and their partners in turn felt less conflict and antagonism within the relationship. Because no romantic relationship can escape conflict, this may suggest that the use of positive reasoning strategies in relationships can help turn a conflict into a more positive conversation in which partners express their needs and learn more about each other. Another interpretation of these results is that positive reasoning strategies may be more effective than more aggressive strategies. Rather than Constructive Interparental 16 just making arguments more pleasant, discussing disagreements in a rational, reason-focused way may help to decrease the amount of antagonism and conflict that partners experience in their relationships. Although the current data cannot establish causal pathways, one possible explanation of the partially mediated relationships between father’s positive reasoning and teen attitudes toward aggression is that positive reasoning may lead to other, earlier aspects of the teen’s life, which subsequently predict teen attitudes in later adolescence. Based on the literature, it seems that teens are likely to use their parents’ successful strategies for negotiating conflict and discussion in their own friendships, and that their friendships in turn seem to influence, or at least foreshadow, outcomes in later adolescence. Teen positive autonomy and relatedness with peers in early adolescence predicted teen attitudes toward aggression in late adolescence, suggesting that teen experiences with early adolescent friendships may shape their views about what is acceptable later on. Father’s positive reasoning predicted teen autonomy and relatedness with peers, which may indicate a pathway through which parental influence manifests itself as teens enter adulthood. Teen aggression as rated by close peer also predicted teen attitudes toward aggression in later adolescence. This finding suggests that aggressive behaviors in earlier adolescence may be important in teens’ formations of their later attitudes about aggression. If for example, they learn that aggressive behavior leads to power within their peer group, teens may learn to endorse aggression as useful or necessary. Past research has proposed that peer selection leads to aggression, rather than the converse idea that aggression leads to maladaptive behavior with peers (Werner & Crick, 2004). This may suggest that friends who reported teens as more aggressive held aggression in higher esteem and have reinforced aggressive attitudes in the teen; on the contrary, friends who disapproved of aggression may have reinforced alternative, more constructive responses to conflict in the teen. The finding that father’s positive reasoning predicts teen aggression in mid adolescence suggests that parental positive reasoning may influence actual teen aggressive behaviors in addition to beliefs about aggression. This may occur as teens internalize repeated behaviors over time into values that they consciously accept. Teen autonomy and relatedness with a close peer in early adolescence predicted close peer report of teen aggression one year later. When these variables are viewed as both predictors and outcomes in this study, pathways of potential influence between factors concerning teen aggression become apparent. It seems that father’s positive reasoning predicts peer variables, which in turn predict how teens view aggression and its place in their later relationships. Physical aggression from fathers to mothers was not a significant predictor of teen attitudes toward aggression in late adolescence, while positive reasoning was significant. This finding is important because it suggests that positive conflict tactics, which have not been studied thoroughly to date, may have a value in explaining human behaviors and attitudes over and above what psychology has traditionally studied. Physical aggression was, however, a significant predictor of antagonistic conflict in teen romantic relationships. When physical aggression is included in the model with positive reasoning, positive reasoning maintains its ability to predict antagonistic conflict. Again, this suggests that positive conflict tactics may be an important construct to consider in explaining behaviors. It also suggests that positive reasoning is not merely the opposite of physical aggression, and that separate processes are at work. Both physical aggression and positive reasoning seem to explain teen romantic relationship antagonistic conflict, indicating that several different conflict styles may exist and have different impacts between parents and their adolescents. Constructive Interparental 17 A major implication of this study is that future research should examine more positive predictors of positive outcomes. Consistent with Seligman’s positive psychology movement, the current study seeks to discover what factors will help people to flourish, not just which factors will cause the most damage (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). The literature contains a wealth of studies on the dangers of child abuse and negative conflict styles between parents in high-risk samples. While these studies have been very helpful in changing the way parenting is viewed, they have omitted many of the behaviors that parents perform in their daily lives. The community sample in the current study provides a useful pool for the exploration of family behaviors under normative conditions. Fortunately, physical violence between parents was not widespread; however, the conflict tactics scale contains pages of questions pertaining to physical violence while it only contains three questions in reference to positive conflict behaviors. Also notably missing on this scale are any questions pertaining to resolution of arguments between parents and attempts to explain the meanings of arguments to their children and adolescents, factors that previous research suggests are important predictors of child and adolescent responses to interparental conflict (Cummings & Wilson, 1999). Another important implication of this study is that there are very different ways to handle conflicts. It serves as a reminder that while conflict is unavoidable in all relationships, there are healthy ways to solve it. Future research should examine other parent conflict tactics that correlate positively with adaptive teen outcomes in the long term. The consensus of most studies predicting adolescent outcomes from parental behaviors is that parents are important role models for their children, for better or for worse. This fact has had legal implications in the state of California, where witnessing domestic violence has been recognized as detrimental to children and held on par with child abuse, even when the children are not directly involved. But a study of what parents do wrong is not enough. Psychologists need to study preventative factors as well, and seek to identify behaviors that lead to more adaptive peer interactions, less antagonistic romantic relationships, and more constructive alternatives to aggression in resolving conflicts. A final implication of this study emphasizes the role of fathers in adolescents’, and especially boys’, lives. While father’s positive reasoning with mother significantly predicted several outcomes, mother’s positive reasoning with father did not. Mothers have been traditionally studied as playing a more integral role in a child’s development. However, results from the current study as well as other studies suggest that this may change as children mature (Phares & Compas, 1999; Allen & Hauser, 1994) . Studies suggest that fathers aid in the adolescent transition from the home to the outside world in a way that mothers do not, perhaps as a result of mothers’ traditional place within the home. Future research should continue to explore the influence of fathers in their adolescents’ lives, as it could eventually change fathers’ involvement with their maturing children. The results of the current study may indicate that fathers are particularly important in the development of male adolescents. A gender interaction that occurred for teen aggression at age 15 as a function of father’s positive reasoning reveals differential results for boys than for girls. Gender-specific follow-up analyses revealed that father’s positive reasoning no longer significantly predicted levels of aggression in girls, which may partly be due to the fact that girls’ friends rated them as very low in aggression in general. For boys, however, father’s positive reasoning became even more significant. This finding may suggest that sons learn about aggression from their fathers in a way that daughters do not, and further research should continue to investigate the father-son relationship in adolescence. Constructive Interparental 18 Limitations of this study include the low Cronbach’s a of the predictor variable, which suggests that the index of positive reasoning used in this study may not be the best measure of the underlying construct of real world conflict strategies, as responses to the items therein were not consistent. This is likely due to the small number of questions comprising the scale, which suggests once again that future research should examine more types of positive predictors. Another limitation of the current study is that participants with father figures were statistically significantly different from the participants without father figures. This limits the generalizability of the results, as the sample studied does not accurately reflect the larger community in terms of gender and income distribution. Finally, the correlational nature of the data precludes any causal conclusions in this non-experimental study. Constructive Interparental 19 References Allen, J. P., Hauser, S. T., & Bell, K. L. (1994). Longitudinal assessment of autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of adolescent ego development and self-esteem. Child Development, 65(1), 179-194. Buehler, C., Krishnakumar, A., & Stone, G. (1998). Interparental conflict styles and youth problem behaviors: A two-sample replication study. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 60(1), 119-132. Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (1990). Peer group behavior and social status. In A. R. Steven & J. D. Coie (Eds.), Peer rejection in childhood (pp. 17-59). New York: Cambridge University Press. Creasey, G., & Hesson-McInnis, M. (2001). Affective responses, cognitive appraisals, and conflict tactics in late adolescent romantic relationships : Associations with attachment orientations. Journal of counseling psychology, 48, 85-96. Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children's future social adjustment. Child Development, 67(5), 23172327. Cummings, E. M. (1998). (was 1999) Stress and coping approaches and research: The impact of marital conflict on children. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 2(1), 3150. Cummings, E. M, & Davies, P. T. (2002). Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(1), 31-63. Cummings, E. M, Goeke-Morey, M. C., & Papp, L. M. (2004). Everyday marital conflict and child aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(2), 191-202. Cummings, E. M., & Wilson, A. (1999). Contexts of marital conflict and children's emotional security: Exploring the distinction between constructive and destructive conflicts from the children's perspective. In M. J. Cox & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), Conflict and cohesion in families: Causes and consequences (pp. 105-129). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Dadds, M. R., Atkinson, E., Turner, C., Blums, G. J., & Lendich, B. (1999). Family conflict and child adjustment : Evidence for a cognitive-contextual model of intergenerational transmission. Journal of family psychology, 13(22), 194-208. Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: an emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 387-411. Du Rocher Schudlich, T. D., & Cummings, E. M. (2003). Parental dysphoria and children's internalizing symptoms: Marital conflict styles as mediators of risk. Child Development, 74(6), 1663-1681. Feiring, C., Deblinger, E., Hoch-Espada, A., & Haworth, T. (2002). Romantic relationship aggression and attitudes in high school students: The Role of Gender, Grade, and Attachment and Emotional Styles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(5), 373–385. Goeke-Morey, M. C., Cummings, E. M., & Harold, G. T. (2003). Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of U.S. and Welsh children. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(3), 327-338. Constructive Interparental 20 Grotpeter, J. K. (1998). Relational aggression, overt aggression, and family relationships. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 58(10B), 5671. Grych, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (1990). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitivecontextual framework. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 267-290. Grych, J. H., Seid, M., & Fincham, F. D. (1992).Assessing marital conflict from the child's perspective: The children's perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Development, 63(3), 558-572. Harold, G. T., Shelton, K. H., & Goeke-Morey, M. C. (2004). Marital conflict, child emotional security about family relationships and child adjustment. Development, 13(3), 350-376. Jurich, A. P., Schumm, W. R., & Bollman, S. R. (1987). The degree of family orientation perceived by mothers, fathers, and adolescents. Adolescence, 22(85), 119-128. Katz, L. F., & Gottman, J. M. (1993). Patterns of marital conflict predict children's internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 940-950. Kempton, T., Thomas, A. M, & Forehand, R. (1989). Dimensions of interparental conflict and adolescent functioning. Journal of Family Violence, 4(4), 297-307. Kinsfogel, K. M., & Grych, J. H. (2004). Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(3), 505-515. Laursen, B. (1995). Conflict and social interaction in adolescent relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 5(1), 55-70. Martin, B. (1990). The transmission of relationship difficulties from one generation to the next. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 19(3), 181-199. Mizokawa, S. T. (2000). Interparental conflict and child and adolescent aggression: An examination of overt and relational aggression. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 60(8-B), 4275. Moretti, M. M., Obsuth, I., & Odgers, C. L. (2006). Exposure to maternal vs. paternal partner violence, PTSD, and aggression in adolescent girls and boys. Aggressive Behavior, 32(4), 385-395. Phares, V., & Compas, B. E. (1992). The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin, 111(3), 387-412. Reese-Weber, M., & Bartle-Haring, S. (1998). Conflict resolution styles in family subsystems and adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27(6), 735752. Rickert, V. I., Vaughan, R. D., & Wiemann, C. M. (2002). Adolescent dating violence and date rape. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 14(5), 495-500. Schlatter, A. K. W. (2001). Parental aggression and adolescent peer relationships. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 61(9-B), 5031. Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. Smith, D. C., & Furlong, M. J. (1994). Correlates of anger, hostility, and aggression in children and adolescents. In M. J. Furlong & D. C. Smith (Eds.), Anger, hostility, and aggression: Assessment, prevention, and intervention strategies for youth (pp. 1538). Brandon, VT: Clinical Psychology Publishing Co. Tencer, H. L. (2005). Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me: The development of friendships among adolescents who report verbal and emotional Constructive Interparental 21 aggression by parents. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 65(10-B), 5424. Werner, N. E., & Crick, N. R. (2004). Maladaptive peer relationships and the development of relational and physical aggression during middle childhood. Social Development, 13(4), 495–514. Wierson, M., Forehand, R., & McCombs, A. (1988). The relationship of early adolescent functioning to parent-reported and adolescent-perceived interparental conflict. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16(6), 707-718. Wolfe, D. A., Scott, K., Wekerle, C., & Pittman, A. (2001). Child maltreatment: Risk of adjustment problems and dating violence in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(3), 282-289.