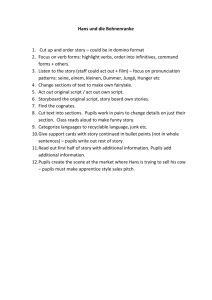

realising the potential

advertisement