Winesburg, Ohio

advertisement

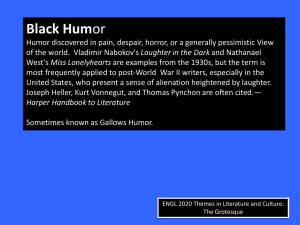

Norman 1 Randy Norman ENGL 3830 Dr. Chase Analytical Paper 1 The Grotesque in Winesburg, Ohio The word “grotesque” is defined in the Cambridge Advanced Leaner’s Dictionary as “strange and unpleasant, especially in a ridiculous or slightly frightening way.” This definition describes Sherwood Anderson’s collection of short stories: Winesburg, Ohio. The collection is episodic, ranging from stories concerning men to women to preachers to children. Each person, according to the old writer who begins the novel, is grotesque because of the way he or she views life and his or her ideas of truth. This idea of truth, an absolute truth searched for by all of the inhabitants of the novel, is Anderson’s way of commenting on the effect of truth and how it makes the characters incomplete, ruined, and unable to live in anything but a fantasy lifestyle. This search for truth creates in the characters a grotesque nature that slowly evolves into an understanding of their condition and allows Anderson to use the Industrial Revolution as a source of the characters sanity; George Willard, the reporter for the local newspaper and the only connection to all the characters in the stories, is the only one who understands this condition and is able to leave the town of Winesburg. This idea of the grotesque is presented by the old man in the prologue of the story. The old man associates the idea of truth being the culprit that creates the grotesque nature of a person. It is the yearning and desire to know this absolute truth that makes each character grotesque. In the prologue, the narrator state, “It was his notion that the moment Norman 2 one of the people took one of the truths to himself, called it his truth, and tried to life is life by it, he became a grotesque, and the truth he embraced became a falsehood” (Anderson 5). It is the idea of each person taking a truth and basing his or her whole existence on it that makes each person grotesque. In a “strange and ridiculous way,” each person takes an idea he or she perceives to be logical and true and bases his or her life on that idea. Anderson is saying that this is a bad way to live. He does this by illustrating the situations he places his characters in. Adolph Myers is the main character in the story Hands. He is known as Wing Biddlebaum, because his hands resemble wings (Anderson 9). He is deemed grotesque because he feels uncomfortable with his large un-normal hands. Readers learn that “They became his distinguishing feature, the source of his fame. Also they made more grotesque an already grotesque and elusive individuality” (Anderson 10). Wing’s hands are his way of expression. Thus, the story is actually about expression and what censures it. Readers learn that “Wing Biddlebaum talked much with his hands” (Anderson 9). He is unable to effectively communicate with his hands; Wing treats them as scars and he continually tries to hide them, “Forever striving to conceal themselves in his pockets or behind his back” (Anderson 9). His hands are grotesque because they are awkward and strange. Wing’s truth is to be able to dream without interference. It is his dreaming that gets him in trouble. While teaching in school, Wing falls off to sleep, and dreams. Wing gets in trouble when, as the narrator tells the reader, “Adolph Myers had walked in the evening or had sat talking until dusk upon the schoolhouse steps lost in a kind of dream. Here and there went his hands, caressing the shoulders of the boys, playing about the tousled heads” (Anderson 13). Wing is accused of child molestation, moves to Winesburg and Norman 3 lives the remainder of his life there. The townspeople’s accusation of child molestation leaves him uncomfortable with his grotesque hands and unsure of what he has done wrong and ostracized for not conforming. His quest to fulfill his idea of “truth” was, in essence the downfall of his existence. The idea of the “grotesque” is prevalent in the story “The Strength of God.” Curtis Hartman is a pastor who is unable to convey his faith in feelings in an outward fashion. He is in a position of authority in the church, yet he is nervous and unable to convey his inborn authority of faith and religion to his congregation because of his nervousness. This inadequacy is explained when Anderson write that he was “by his nature very silent and reticent. To preach, standing in the pulpit before the people, was always a hardship for him and from Wednesday morning until Saturday evening he thought of nothing but the two sermons that must be preached on Sunday” (Anderson 171). What is strange and unpleasant in Mr. Hartman is that he is a preacher who reveals his human emotions. Preachers, in theory, are put on a pedestal and examined because they are deemed examples of what the congregation of each church is supposed to be. Reverend Hartman is grotesque because he finds freedom in the viewing of a woman’s bare shoulders. Given his line of work, he is not expected to enjoy the sexual excitement of anyone but his wife. This sexual arousal is what makes Reverend Hartman grotesque. In his search for truth, Reverend Hartman finds that his “truth” is his unfulfilled sexual desires have instilled in him a voyeuristic attitude that allows him to escape his normal, monotonous reality and allows him moments of fantasy when he views the woman nude through the window. His “truth” leads to the grotesque reality of his suppressed sexual environment. Examples of this continuing change in Reverend Hartman’s life are evident Norman 4 when “he began to want also to look again at the figure lying white and quiet in the bed” (Anderson 175), and then again when “With the stone he broke out a corner of the window and then locked the door and sat down at the desk before the open Bible to wait. When the shade of the window to Kate Swift’s room was raised he could see, through the hole, directly into her bed, but she was not there.” (Anderson 175). The reader realizes that Hartman ponders this: “I want to look at the woman and to think of kissing her shoulders and I am going to let myself think what I choose.” (Anderson 179). It is the idea of his grotesque reality that makes him a real character; Reverend Hartman is a legitimate pastor who lives in everyday life in the natural world we inhabit. The character throughout the collection of stories who integrates each individual citizen and story is George Willard, the reporter for the local newspaper in Winesburg. George is the person who everyone in the town comes to tell their problems. He is the only connection the grotesque individuals of Winesburg have to connect themselves to each other. It is this loneliness that attributes to their grotesqueness. This idea of isolation and loneliness is prevalent throughout the stories; throughout the stories, the word “loneliness” is used at least nine times, one time being the name of one of the stories. The story Loneliness refers to a fantasy world of New York City, but in reality ends up back in Winesburg because of his detachment from the outside world. This is the basis for the idea of loneliness. Each character is lonely and involved in their personal fantastical dreams. No-one is able to comprehend and live in a natural reality. The only person who can link together the citizens of the town is George. This is done by his profession of being the reporter for the local paper. In essence, George is the “priest” of the town to whom everyone comes to reveal their sins and emotions. Norman 5 Many characters in the story want something from George Willard. As a congregation wants repentance for their sins from their priest, the residents (grotesques) of Winesburg want George to “speak what is in their hearts and thus re-establish their connection with mankind” (Conner1). George Willard appears in fifteen of the twentyfour stories in Winesburg, Ohio. George’s life is present as the backdrop of the book. As in the definition of the “grotesque,” George Willard becomes paradoxical to grotesque in the last story of the collection, entitled “Departure.” In this final story, George understands the need to move out of a town that is hindering his ability to grow into an adult. In fact, Anderson refers to Winesburg as George’s “background on which to paint the dreams of his manhood” (Anderson303). In a turn from the grotesque, George decides not to find his absolute truth; he feels that progress will be made in the setting of another town. It is assumed that George leaves for a larger town. This assumption leads into the idea of industrialization and modernization. The concept of the grotesque fuses with the development of the industrial age in both practical affairs and art. The thought of industrialization was a strange and frightening concept to the people of the early twentieth century. Customs and traditions were at the brink of being thrown away due to the invention of many different machines that would make mass production and assembly lines possible. With these new inventions comes anxiety of the unknown. Anderson uses these ideas and puts them to practice in his novel Winesburg, Ohio. The town of Winesburg is a sleepy, anywhere USA town. It is assumed that this town is equipped with neither the amount of people nor the will to accommodate an individual revolution. Each of the townspeople suffers for this as well. Each individual invoked in the novel has a problem that results from the dilemma of Norman 6 seeking truth. This truth is what creates problems because it is an idea. This idea of truth is faulty because many different truths exist in the realm of society: God’s truth, secular truth, the gospel truth, all these ideas are manifested in human beings to bring peace. It is this morality that each individual seeks. It is self contained. The people in Winesburg do not see the path to truth as being industrialization. Anderson makes good points for the arrival of his new phase of life through his illustration of the problems that arise because of a lack of new social settings. The past ways bring problems; the future, unknown to the inhabitants of Winesburg, is full of promise. The first thing they have to realize, though, is that for the future to progress, they must give up the social settings in which their problems have harvested. This new change, out of grotesque and into the age of modern life, is Anderson’s goal in his writings and in his heart. Norman 7 Works Cited Anderson, Sherwood. Winesburg, Ohio: A Group of Tales if Ohio Small-Town Life. New York: Modern Library, 1919. Conner, Mark C. “Fathers and Sons: Winesburg, Ohio and the Revision of Modernism.” Studies in American Fiction 29.2 (2001): 209+.