The Global Crisis, 1921–1941

advertisement

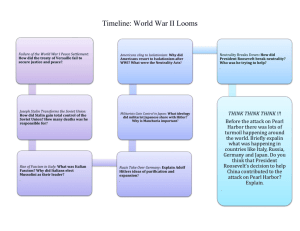

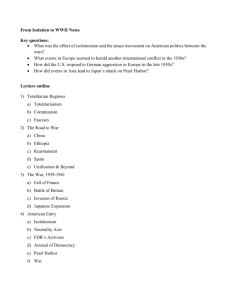

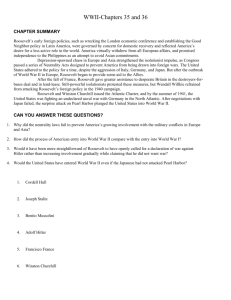

CHAPTER 27 The Global Crisis, 1921–1941 CHAPTER SUMMARY Following the disillusionment of World War I, the U.S. government made the conscious decision to avoid international commitments that might lead to involvement in another war. Never again, Americans wanted to believe, would the United States send an army to Europe. But neither the government nor its people could—or desired to—avoid all contact with the rest of the world. Thus international trade continued and in some cases expanded. So did travel and cultural contacts. At the same time, U.S. diplomats sought to ensure world peace through multinational agreements to avoid an arms race, going even as far as to “outlaw” war in 1928. The desire to keep American troops at home extended to this hemisphere as well. Both the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations took steps to improve strained relations with the countries of Latin America. Europe, however, was soon to be another matter. So was Asia. By the early 1930s, crises on both continents were brewing as a result of aggressive actions on the part of Japan, Germany, and Italy. The initial American response to the aggression was one of renewed commitment to isolationism. Blatant land grabs by Japan in 1931, Italy in 1935, and Germany in 1936 were met with verbal rebuke by the United States but little else. In the mid-1930s, Congress passed a series of Neutrality Acts, which had the effect of denying a commitment to historic American neutral rights. Insistence on those rights, isolationists argued, had helped push the United States into war in 1917; however, events in the late 1930s led the Roosevelt administration to abandon this legislation. As Axis aggression grew bolder, President Roosevelt gradually began to chip away at the neutrality policies. He had to move cautiously, however, because the American public was not fully supportive of this effort. Following the Japanese invasion of China, Roosevelt delivered his “quarantine” speech, which issued a vague call on the peace-loving states to quarantine aggressor states. Even this mild attempt at interventionism was roundly criticized by the public. Following the start of another world war in Europe in September 1939, public attitudes shifted in alarm over the early successes of Germany. Roosevelt felt empowered to gradually ease the United States closer to participation in war. Programs such as “lend-lease” replaced hard-and-fast American neutrality. All such gradual steps came to a sudden end on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese made a surprise attack on the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. The next day the United States declared war on Japan. A few days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. Isolationism was history, and the United States entered World War II suddenly determined and unified. OBJECTIVES A thorough study of Chapter 27 should enable the student to understand: 1. The extent and nature of American isolationism in the 1920s 2. The effects of World War I and the Great Depression on American foreign policy 3. The pattern of Japanese, Italian, and German aggression during the 1920s and 1930s and the United States’ response to it 4. The factors that led to the passage of neutrality legislation in the mid-1930s and its effects on Brinkley 5e, IM, Ch 27 | 1 of 3 American foreign policy 5. The specific sequence of events that brought the United States into World War II MAIN THEMES 1. How the United States moved during the 1920s to increase its role in world affairs, while attempting to avoid political and military commitments 2. Why and how the United States moved toward isolationism and how it tried to legislate neutrality in the face of mounting world crises 3. How war in Europe and Asia gradually altered the United States’ foreign policy until the attack on Pearl Harbor finally sparked American entry into World War II POINTS FOR DISCUSSION 1. Explain and evaluate the objectives, means, and results of American diplomacy during the 1920s. How successful was the United States in achieving its goals? What were the weaknesses in American foreign policy? 2. How and why did the early years of the Great Depression alter international affairs and American diplomacy? 3. Explain the relationship between American attitudes toward World War I and the isolationist sentiment and neutrality legislation of the 1930s. Did the neutrality laws make the United States more or less secure? Did these laws make war in Europe more or less likely? How so? 4. How and why did American public opinion shift from favoring neutrality in 1935 to favoring intervention in 1941? Which groups of Americans were the first to see the danger of fascism and why? In what sense was the Spanish Civil War a “dress rehearsal” for World War II? 5. How did President Roosevelt attempt to get around neutrality legislation? Were his actions legal? Were they justified by the events of the times? What might have happened if he had not taken these actions? 6. Why did the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor? What did they hope to accomplish? Why was the United States caught unprepared for the attack? How successful was the attack for Japan in the short term? In the long term? What were the consequences of the attack in the United States? INTERPRETATIVE QUESTIONS 1. To what degree was isolationism a factor in the United States during the 1920s? Was the dual policy of economic penetration and arms limitation an effective approach? Why or why not? What might have made more sense? 2. Compare and contrast the American response to the onset of World War I and World War II. Specifically compare Presidents Wilson and Roosevelt as leaders of a people desirous of peace while Europe was at war. BIBLIOGRAPHY A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh (1998) Warren Cohen, Empire Without Tears: America’s Foreign Relations, 1921-1933 (1987) Brinkley 5e Instructor's Manual, Ch27 | Page 2 of 3 Wayne S. Cole, Roosevelt and Isolationists, 1932-1945 (1983) Robert Dallek, Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945 (1979) Robert Ferrell, American Diplomacy in the Great Depression (1970) Irwin F. Gellman, Good Neighbor Diplomacy: United States Policies in Latin America, 19331945 (1979) Akira Iriye, The Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations, Vol. 3: The Globalizing of America, 1913-1945 (1993) _____, The Origins of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific (1987) Manfred Jonas, The United States and Germany (1984) Joseph Lash, Roosevelt and Churchill (1976) Melvyn P. Leffler, The Elusive Quest: America’s Pursuit of European Stability and French Security, 1919-1933 (1979) Gordon Prange, Pearl Harbor (1986) Lawrence Wittner, Rebels Against War (1984) For Internet resources, practice questions, references to additional books and films, and more, see this book’s Online Learning Center at www.mhhe.com/unfinishednation5. Brinkley 5e, IM, Ch 27 | 3 of 3