Danto

advertisement

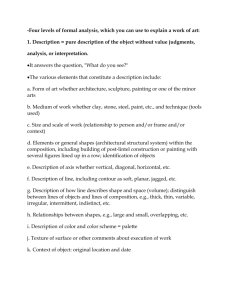

Arthur Danto “Works of Art and Mere Things” from his book The Transfiguration of the Commonplace 1981 "Arthur Danto is an American analytic philosopher and art critic who has spent the last half century teaching at Columbia University. He is wide-ranging in his interests, but his most influential work falls into two areas. Firstly he has been one of the bridges between the two divergent traditions of thought in modern Western philosophy, by taking some major figures from the history of Continental philosophy, particularly Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre, and writing about their works treating them as if they were AngloAmerican analytic philosophers. Purists may pale at the very idea, but Danto's deep scholarship and clear writing style has pulled this stunt off with considerable success, reconnecting these thinkers to ongoing debates in the analytic tradition and thus vastly increasing their influence among the academics of Britain and North America. Until quite recently many professional philosophers in Britain dismissed Nietzsche by saying that he was more a poet or a literary figure rather than a philosopher as such; this attitude has now completely disappeared and Danto is due some of the credit for that. He has illuminated these thinkers from a new angle and introduced the complexities of their ideas to people who might otherwise have shied away because of the unfamiliar terminology and unexplained background assumptions in their works. Danto's second major area of influence has been in aesthetics, where he has worked on the classic problem of how you decide whether or not something is a work of art. Danto has argued that what all works of art have in common is that they all relate in some way to an `artworld', to an accepted artistic theory, or to the history of art as a whole. So if someone puts a toilet in the middle of an art gallery and calls it art, then it is art if (and only if) it makes sense in the history of the development of art over the centuries. Maybe the history of art was just ready for a toilet in an art gallery then, and what distinguishes it from ordinary toilets are the interpretations which those educated in art history put upon it. Danto has a view of the development of the history of art inspired by Hegel. He claims that eventually, through its growing consciousness of itself, art becomes philosophy and thus comes to an end. Some critics claim that the Danto approach is overly inspired by a few movements in modern art and doesn't take into account the diversity of art over the centuries, but Danto has written as an art critic on a very wide range of artistic forms, even including science fiction writing (of which he is dismissive: "Nothing so much belongs to its own time as an age's glimpses into the future."). Despite his insistence that art becomes philosophy, Danto has never been under any illusions about the status of aesthetics in contemporary debate, wryly commenting that aesthetics is currently "about as low on the scale of philosophical undertakings as bugs are in the chain of being."" © Rick Lewis 2000 (This article first appeared in Philosophy Now Issue 27, 2000) [taken from the web] 1) Consider various all-red paintings that look exactly alike: one described by Kierkegaard of Israelites crossing the Red Sea, one by a Danish portraitist titled Kierkegaard’s Mood, Red Square (realist), Red Square (minimalist version), Nirvana, Red Table Cloth, canvas grounded in red lead prepared by Giorgione (not an artwork), a surface painted but not grounded in red lead (not an artwork, just a thing with paint on it): the illustrated catalog would look all the same, even though the paintings belong to diverse genres. 2) J (a young egalitarian artist) thinks they should all be called “work of art” and so he paints a work that resembles the last example and insists that his is a work of art and wants it hung in the show. a) Danto thinks Js work is rather empty compared to the narrative richness of Israelites, the impressive depth of Nirvana, etc. b) Yet it is not empty in the way that a mere expanse of red painted canvas is “empty.” c) The statement that it was empty was an aesthetic judgment which presupposes its object is an artwork. d) His work is literally empty, as are all the works in the show, but it is also “empty” in the art appraisal sense of “empty.” 3) J calls his work Untitled, which is a title, not a statement of fact, and the mere thing J supports is not titled, it is unentitled to a title. a) A title is frequently a direction for interpretation or reading (although that may not always be helpful). b) J says his work is about nothing, but so is Nirvana. c) Danto: The red expanse is also not about anything, but that is because it is a thing, and things lack aboutness, and artworks are typically about something (Js work is unusual in this respect). [but is Js work really about nothing?] 4) Danto: J has made a minimal artwork but has not made an artwork out of a bare red expanse. Thus Js gesture was pointless: he has left unbreached the boundaries between artworks and the world of just things. a) It is not simply because J is an artist that his work is art, for not everything touched by an artist turns into art (Giorgione’s primed canvas). b) J then declares the contested red expanse a work of art, like Duchamp with his snowshovel, and I (Danto) allow it, but what has been achieved? [Dickie would say that this settles the question, but Danto does not agree.] 5) [Danto does not believe that beauty is necessary for art.] There are works of art which have material counterparts that are beautiful in the way certain natural objects are. a) [Danto seems to believe that an artwork has two sides, the material counterpart and the interpretation. This is much like the view that Heidegger criticizes.] b) People with aesthetic sensitivity spontaneously respond to things like gemstones, birds and sunsets. c) Suppose there was a group of people (“barbarians”) who lacked the concept of art but still saw as beautiful what we consider as paradigms of beauty, e.g. glowing iridescent things, and also certain works of art whose material counterparts are beautiful, seeing them as beautiful things. d) Imagine them sparing those works of art which happen to have beautiful material counterparts, including some paintings with gold leaf etc., but not some Rembrandts etc. e) Appreciation of the latter works would require them to be perceived first as artworks, and the barbarians in this thought experiment don’t have the concept of “art.” f) Conclusion of the thought experiment: the relationship between the artwork and the material counterpart must be gotten right for aesthetics to have any bearing on appreciation of art. g) And the cognitive apparatus required for innate aesthetic sense to come into play in our appreciation of art cannot be innate [this is an attack on Kant?]. 6) Why were Warhol’s Brillo boxes worth more than the original ones, which were in fact designed by an artist? Why is a primed canvas of Giorgione not art? a) The answer is historical. b) Not everything is possible at every time: certain artworks simply could not be inserted as artworks into certain periods of art history, for example Duchamp’s snowshovel into the 13th century. [So the designer could not have made his work art, but Warhol could, a few years later?] 7) To see something as art depends on an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art. a) Art is the kind of thing that depends for its existence upon theories. b) [So Danto must mean that whether something is art depends on whether someone can see it as art]. c) Without theories black paint is just black paint. d) There could not be an artworld without theory: it is logically dependent on theory. e) Theory is so powerful it detaches objects from the real world and makes them part of a different world, an art world, a world of interpreted things. f) There is an internal connection between the status of an artwork and the language with which artworks are identified as such. g) Nothing is an artwork without an interpretation that constitutes it as such. [Thus Danto’s theory would be different from Dickie’s. Dickie does not demand that something be interpreted as art.] In what ways is Danto’s theory like Dickie’s and in what ways different? Both Danto and Weitz think that theory is important. But Danto thinks it is important in identifying something as art. What would Weitz say in response? Is there a problem with Danto’s radical separation of art from ordinary things? Danto is strangely like Plato in one way. How?