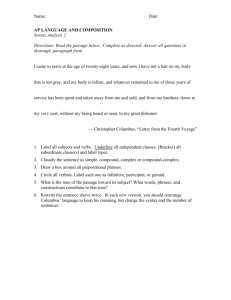

Christopher Columbus and his Legacy

advertisement

Christopher Columbus and his Legacy By Dr Thomas C Triado Introduction We can only understand the explorer Christopher Columbus, and the forces that motivated him, through an understanding of the 15th-century world in which he lived. It was a dynamic century, which saw many radical changes. New political, economic, religious and dynastic forces were at work throughout western Europe, and all of these challenged feudal society - sealing the fate of the landed aristocracy and, to some degree, that of the Church in Rome. Changes affected all classes of society, but none so profoundly as the bourgeoisie. It was during the 15th century that a new class of merchants, ship-builders, tradesmen and others appeared - living in and around Europe's old medieval towns. This class was to ally itself with the monarchs of Europe, and nothing illustrates this merchant-monarch alliance better than the career of Christopher Columbus. A son of Genoa and a member of the new aspiring class, Columbus' ultimate success came as a direct result of having forged an unparalleled alliance with Isabella and Ferdinand, the Catholic monarchs of Spain Background to the Age of Discovery Although there were some attempts on the part of China to extend its influence westward around India before the 15th century, almost all subsequent efforts at discovery of far-away lands and seas have been made by western explorers. This is why there has been such an overwhelming European bias to the traditional commemoration of the Age of Discovery of the 15th and 16th centuries. The explorations of this time led to a worldwide expansion of European power in many ways. As always, it was the victor who wrote the history of the age, and the people and countries that made the discoveries were the main beneficiaries of the new wealth and glory. Clearly, Europeans were not the only people to initiate voyages of discovery. The peoples of North Africa and Asia, long before the 15th century, had sailed into unknown seas and explored distant lands. These discoveries, however, for the most part, either were kept secret to protect lucrative trade routes or resulted in only small additions to a larger picture. And before the time of the printing press, which led to the great expansion of learning at the time of the European Renaissance (roughly 1400 to 1550), the discoveries were known only within limited regions of the world. Exploration on a grand scale can only occur when great changes in technology or in political power make new ways of travelling possible. The voyages of the Europeans in the 15th and 16th centuries were inspired by the great political changes of the age, as Christian powers expelled Muslim forces from their lands, and the new merchant class competed for access to lucrative foreign markets. These voyages in search of trade routes were indeed on a 'grand' scale, and those explorers who leapt across continents and oceans are today remembered better than those who extended their boundaries less dramatically. Except for the discoveries of the Vikings at the turn of the second millennium, little exploration originated from continental Europe in the centuries immediately preceding the 15th century. During the Medieval period, intellectual curiosity was shaped and contained by the Catholic Church. Only a few explorers investigated distant lands - and information was not generally shared with the ordinary people. Looking east Eventually, however, the general populace resumed its historic interest in the mysterious east, and adventurers and merchants began to rekindle ancient Greek and Roman rumours of eastern lands. When Europe ventured a look in that direction, it saw a great new empire, one with which the Church hoped to forge links, and which offered rich trading opportunities. Until the rise of the Mongol Empire (roughly 1206 to 1368) travelling in Asia had been so dangerous that most explorers either turned back or never returned at all. In the 13th century, however, the Mongols under powerful khans - unified Asia, and gave to that continent a peace it had never previously known. It is no accident, then, that the century of Mongolian supremacy coincides with the first great era of modern European exploration. Some time around 1260, two Venetian merchants, the brothers Niccolo and Maffeo Polo, embarked on an eastward journey that ultimately made contact with the fabled empire of the Mongol Khan (China). This first contact led to one of the greatest adventures of all time, that of Niccolo's son, Marco Polo, who made a famous voyage of discovery to China. The new bourgeoisie liked what they heard from Marco Polo on his return, essentially because of the prospect of trade with the east. Here begins the period of greatest activity in the history of exploration, at the start of a new era, the modern world. The Age of Discovery witnessed unimaginable achievements. Europeans discovered two continents previously unknown to them, rounded a third one, mapped a new ocean and made contact with new civilisations. So great, in fact, was the flood of information being sent back home, that the European mind seemed at times unable to assimilate all of it. Royal patronage: Portugal It was the rise of the European national monarchies, with their profound political and dynastic influence, that most helped to encourage the new spirit of adventure. To a 15th-century explorer, royal sponsorship was a necessity, not a luxury. Who else but a monarch could conduct diplomatic relations, colonise land and create an ultramarine government? It was no coincidence that the Age of Discovery occurred at the same time as the appearance of the first truly national governments in western Europe. In addition to royal backing, however, any successful commercial enterprise also needed the support of the bourgeoisie. The Portuguese were a united nation throughout the 15th century - while Spain was still fighting the Muslims - so was in a position to look beyond its own shores a full century or more earlier than its neighbour. This small, Atlantic coastal kingdom thus got a head start on the competition, and soon learned that maritime trade was more profitable than anyone had imagined. Already at the time of Prince Henry 'the Navigator' (1394-1460), the Portuguese were extending exploration down the west coast of Africa in hopes of finding passage to the east around the tip of Africa. This enterprise reinforced the lesson that a strong political and military base was needed from which to sustain new explorations. It was well known that the reigning monarch at the time of Columbus, King John II, who had come to power in 1481, was committed to discovering a direct sea route to the Indian Ocean and the Far East. And Prince Henry's unfulfilled dream of circumnavigating Africa was also one of King John's passions. It was with this knowledge that Columbus, having moved to Portugal from the place of his birth, decided to seek royal patronage in Portugal. He had been devising a plan for many years to reach the Indies in the east by travelling west - he called this his 'Enterprise of the Indies' - and Portugal would have seemed the natural country to support him. Despite this, however, and despite his many personal connections with Portugal, Columbus was not granted the royal patronage he sought. According to tradition the request was denied on the ground that it was too expensive, that Columbus was only a 'visionary' and was wrong about distances and measurements, and that such a plan was contrary to Portugal's commitment to finding an eastward route to Asia by travelling around Africa. Royal patronage: Spain As backing from royal courts in Portugal - and also France and England - fell through, Columbus took his young son and moved to Spain in 1485. His intention now was to approach the Spanish monarchs with his Enterprise of the Indies. In 1488, with his Portuguese rival Bartolomeu Dias having finally made the voyage down the coast of Africa and around its southern tip, Columbus made his approach. Queen Isabella was doubtful about his idea of reaching eastern markets by travelling westwards, although intrigued by them. But the time was not right for her to sanction a voyage of discovery - the recapture of Granada from the Muslims was the focus of her attention. Once Granada fell, in 1492, however, and the Iberian Peninsula was comfortably under Catholic control, Columbus's enterprise seemed more promising - at last he gained the commission he had wanted for half of his life. On 3 August 1492, at the age of 41, Columbus set sail from Palos, on the Portuguese coast, for the Canary Islands, with a crew of 96, aiming to reach Asia by this route. Thirty-five days westwards from the Canaries, on the night of 11-12 October, a light on land ahead was spotted from the ship. The next morning a new era for the world began when Columbus, with a handful of excited but weary voyagers, set foot on a Caribbean island, an island called Guanahaní by its inhabitants. Consequences of discovery Admiral Columbus made three more trips in the next 12 years to that part of the New World that we now know as the West Indies and South America. He returned home for the final time in 1504. However, in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary, he maintained until his death that he had discovered lands that were part of the Old World; and he never abandoned his belief that he had connected Europe and Asia. So convinced of this was he that he called the newly found territories the Indies, and the people of those lands Indians. (Though there was no country called India at this time, all lands east of the Indus River, which rises in the Himalayas and runs through present-day Kashmir and Pakistan to the Arabian Sea, were referred to in a generic way as the Indies.) While others suggested that the discoveries of Columbus represented a completely new world, unknown to the ancients, Columbus acknowledged only that the 'Asian' islands were more numerous than he had imagined. Intellectually, he had a view of the earth that was much smaller than it is in reality. He overestimated the size of the Eurasian continent, accepted Marco Polo's belief that Japan was 1,500 miles east of China, and seriously underestimated the circumference of the world. So in his own mind he was exactly where he thought he should be when he spotted the islands of the Caribbean Sea - he thought he was in the 'East' Indies. Celebrated more than any other explorer in history, Columbus went to his grave without the vaguest idea of which part of the world he had actually discovered. Despite this misplaced belief, his achievements were enormous. His lifetime at sea had taught him a sailor's sixth sense, and his navigational instincts are still legendary today. The routes he took to and from the newly found lands are the ones we still use; his choice of the Atlantic Canary Current was pure genius. He was also an excellent ship's captain, and his use of dead reckoning was so accurate that he could return to the faraway ports discovered on his earlier voyages. Although his discovery of new lands led to the nearly complete destruction of the people of those lands, and their environment, Columbus appreciated the beauty of the places he discovered. 'Before me', he said, as he surveyed the islands of the Caribbean '...is the bounty of God's handiwork'. Above all, however, Christopher Columbus opened up new worlds to Europe, and in conclusion, it is hard to overstate the significance of these discoveries, nor their global impact. Much has been written about the Columbian Exchange - the exchange of plants and animals, of diseases, of human beings and of cultures - and its intellectual impact. And it is certainly the case that during the Age of Discovery western Europeans acquired the ability to exchange information with nearly all parts of the world. As one of the great thinkers of the age, and one who led the way, Columbus deserves recognition for the intellectual transformation that took place at that time. As a result of his vision, the modern age was ushered in, and the world was never to be the same again.