Chapter 7

Digging Deeper

Contents:

| REALIZED GAIN OR LOSS | RECOVERY OF CAPITAL DOCTRINE | PROPERTY ACQUIRED

FROM A DECEDENT | DISALLOWED LOSSES | CONVERSION OF PROPERTY FROM

PERSONAL USE TO BUSINESS OR INCOME-PRODUCING USE | ADDITIONAL

COMPLEXITIES IN DETERMINING REALIZED GAIN OR LOSS | LIKE-KIND PROPERTY |

EXCHANGE REQUIREMENT | BASIS AND HOLDING PERIOD OF PROPERTY RECEIVED |

AMOUNT REALIZED FROM CONDEMNATION | ROLLOVER OF GAIN FROM QUALIFIED

SMALL BUSINESS STOCK INTO ANOTHER QUALIFIED SMALL BUSINESS STOCK—§ 1045 |

SALE OF A PRINCIPAL RESIDENCE—§ 121 | INVOLUNTARY CONVERSION AND USING §§

121 AND 1033 |

REALIZED GAIN OR LOSS

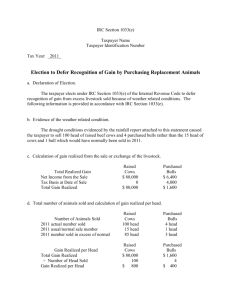

1. Capital Recoveries.

Amortizable bond premium. The amortization deduction is allowed for taxable bonds because the

premium is viewed as a cost of earning the taxable interest from the bonds. The reason the basis

of taxable bonds is reduced is that the amortization deduction is a recovery of the cost or basis of

the bonds.

RECOVERY OF CAPITAL DOCTRINE

2. Relationship of the Recovery of Capital Doctrine to the Concepts of Realization and

Recognition. The general rules for the relationship between the recovery of capital doctrine and

the realized and recognized gain and loss concepts are summarized as follows:

Rule 1. A realized gain that is never recognized results in the permanent recovery of

more than the taxpayer’s cost or other basis for tax purposes. For example, noncorporate

taxpayers may exclude from gross income 50 percent of any gain realized on the sale of

qualified small business stock held for more than five years under § 1202 (see Chapter

8).

Rule 2. A realized gain on which recognition is postponed results in the temporary

recovery of more than the taxpayer’s cost or other basis for tax purposes. For example,

the recognition of gain from an exchange of like-kind property under § 1031 or an

involuntary conversion under § 1033 may be deferred until a subsequent year, as

discussed later in this chapter.

Rule 3. A realized loss that is never recognized results in the permanent recovery of less

than the taxpayer’s cost or other basis for tax purposes. For example, a loss on the sale

of an automobile held for personal use is not deductible.

Rule 4. A realized loss on which recognition is postponed results in the temporary

recovery of less than the taxpayer’s cost or other basis for tax purposes. For example,

recognition of a loss on the exchange of like-kind property under § 1031 may be deferred

until a subsequent year, as discussed later in this chapter.

PROPERTY ACQUIRED FROM A DECEDENT

3. Survivor's Share of Property. Both the decedent’s share and the survivor’s share of

community property have a basis equal to the fair market value on the date of the decedent’s

death.1 This result applies to the decedent’s share of the community property because the

property flows to the surviving spouse from the estate (fair market value basis is assigned

to inherited property). Likewise, the surviving spouse’s share of the community property is

deemed to be acquired by bequest, devise, or inheritance from the decedent. Therefore, it also

has a basis equal to the fair market value.

Example: Floyd and Vera reside in a community property state. They own as community property

200 shares of Crow stock acquired in 1984 for $100,000. Floyd dies in 2008, when the securities

are valued at $300,000. One-half of the Crow stock is included in Floyd’s estate. If Vera inherits

Floyd’s share of the community property, the basis for determining gain or loss is $300,000,

determined as follows:

Vera’s one-half of the community property (stepped up from

$50,000 to $150,000 due to Floyd’s death)

Floyd’s one-half of the community property (stepped up from

$50,000 to $150,000 due to inclusion in his gross estate)

Vera’s new basis

$150,000

150,000

$300,000

In a common law state, only one-half of jointly held property of spouses (tenants by the entirety or

joint tenants with rights of survivorship) is included in the estate.2 In such a case, no adjustment

of the basis is permitted for the excluded property interest (the surviving spouse’s share).

Example: Assume the same facts as in the previous example, except that the property is jointly

held by Floyd and Vera who reside in a common law state. Floyd purchased the property and

made a gift of one-half of the property to Vera when the stock was acquired. No gift tax was paid.

Only one-half of the Crow stock is included in Floyd’s estate. Vera’s basis for determining gain or

loss in the excluded half is not adjusted upward for the increase in value to date of death.

Therefore, Vera’s basis is $200,000, determined as follows:

Vera’s one-half of the jointly held property (carryover basis of

$50,000)

Floyd’s one-half of the jointly held property (stepped up from

$50,000 to $150,000 due to inclusion in his gross estate)

Vera’s new basis

$ 50,000

150,000

$200,000

PROPERTY ACQUIRED FROM A DECEDENT

4. General Rules. For inherited property, both unrealized appreciation and decline in value are

taken into consideration in determining the basis of the property for income tax purposes.

Contrast this with the carryover basis rules for property received by gift.

DISALLOWED LOSSES

5. Related Taxpayers. If income-producing or business property is transferred to a related

taxpayer and a loss is disallowed, the basis of the property to the recipient is the property’s cost

to the transferee. However, if a subsequent sale or other disposition of the property by the original

transferee results in a realized gain, the amount of gain is reduced by the loss that was previously

disallowed.3 This right of offset is not applicable if the original sale involved the sale of a personal

use asset (e.g., the sale of a personal residence between related taxpayers). Furthermore, the

right of offset is available only to the original transferee (the related-party buyer).

Example: Pedro sells business property with an adjusted basis of $50,000 to his daughter,

Josefina, for its fair market value of $40,000. Pedro’s realized loss of $10,000 is not recognized.

How much gain does Josefina recognize if she sells the property for $52,000? Josefina

recognizes a $2,000 gain. Her realized gain is $12,000 ($52,000 less her basis of

$40,000), but she can offset Pedro’s $10,000 loss against the gain.

How much gain does Josefina recognize if she sells the property for $48,000? Josefina

recognizes no gain or loss. Her realized gain is $8,000 ($48,000 less her basis of

$40,000), but she can offset $8,000 of Pedro’s $10,000 loss against the gain. Note that

Pedro’s loss can only offset Josefina’s gain. It cannot create a loss for Josefina.

How much loss does Josefina recognize if she sells the property for $38,000? Josefina

recognizes a $2,000 loss, the same as her realized loss ($38,000 less $40,000 basis).

Pedro’s loss does not increase Josefina’s loss. His loss can be offset only against a gain.

Since Josefina has no realized gain, Pedro’s loss cannot be used and is never

recognized. This part of the example assumes that the property is business or incomeproducing property to Josefina. If not, her $2,000 loss is personal and is not recognized.

The loss disallowance rules are designed to achieve two objectives. First, the rules prevent a

taxpayer from directly transferring an unrealized loss to a related taxpayer in a higher tax bracket

who could receive a greater tax benefit from the recognition of the loss. Second, the rules

eliminate a substantial administrative burden on the Internal Revenue Service as to the

appropriateness of the selling price (fair market value or not). The loss disallowance rules are

applicable even where the selling price is equal to the fair market value and can be validated

(e.g., listed stocks).

The holding period of the buyer for the property is not affected by the holding period of the seller.

That is, the buyer’s holding period includes only the period of time he or she has held the

property.4

CONVERSION OF PROPERTY FROM PERSONAL USE TO BUSINESS OR INCOMEPRODUCING USE

6. Example: At a time when his personal residence (adjusted basis of $140,000) is worth

$150,000, Keith converts one-half of it to rental use. The property is not MACRS recovery

property. At this point, the estimated useful life of the residence is 20 years and there is no

estimated salvage value. After renting the converted portion for five years, Keith sells the property

for $144,000. All amounts relate only to the building; the land has been accounted for separately.

Keith has a $2,000 realized gain from the sale of the personal-use portion of the residence and a

$19,500 realized gain from the sale of the rental portion. These gains are computed as follows:

Original basis for gain and loss—adjusted basis on

date of conversion (fair market value is higher

than the adjusted basis)

Personal

Use

Rental

$70,000

$70,000

Depreciation—five years

None

Adjusted basis—date of sale

$70,000

$52,500

72,000

72,000

$ 2,000

$19,500

Amount realized

Realized gain

17,500

As discussed later in this chapter, Keith can exclude the $2,000 gain from the sale of the

personal-use portion of the residence under § 121. If the § 121 exclusion applies, only $17,500

(equal to the depreciation deducted) of the $19,500 realized gain from the rental portion is

recognized.

Example: Assume the same facts as in the preceding example, except that the fair market value

on the date of conversion was $130,000 and the sales proceeds are $90,000. Keith has a

$25,000 realized loss from the sale of the personal-use portion of the residence and a $3,750

realized loss from the sale of the rental portion. These losses are computed as follows:

Original basis for loss—fair market value on date of

conversion (fair market value is lower than the adjusted

basis)

Personal

Use

Rental

N/A

$65,000

Depreciation—five years

None

Adjusted basis—date of sale

$70,000

$48,750

45,000

45,000

($25,000)

($ 3,750)

Amount realized

Realized gain/(loss)

16,250

The $25,000 loss from the sale of the personal-use portion of the residence is not recognized.

The $3,750 loss from the rental portion is recognized.

ADDITIONAL COMPLEXITIES IN DETERMINING REALIZED GAIN OR LOSS

7. Amount Realized. The calculation of the amount realized may appear to be one of the least

complex areas associated with property transactions. However, because numerous positive and

negative adjustments may be required, this calculation can be complex and confusing. In

addition, determining the fair market value of the items received by the taxpayer can be difficult.

The following example provides insight into various items that can affect the amount realized.

Example: Ridge sells an office building and the associated land on October 1, 2008. Under the

terms of the sales contract, Ridge is to receive $600,000 in cash. The purchaser is to assume

Ridge’s mortgage of $300,000 on the property. To enable the purchaser to obtain adequate

financing, Ridge is to pay the $15,000 in points charged by the lender. The broker’s commission

on the sale is $45,000. The purchaser agrees to pay the $12,000 in property taxes for the entire

year. The amount realized by Ridge is calculated as follows:

Selling price

Cash

Mortgage assumed by purchaser

Seller’s property taxes paid by

purchaser ($12,000 9/12)

$600,000

300,000

9,000 $909,000

Less

Broker’s commission

$ 45,000

Points paid by seller

15,000

Amount realized

(60,000)

$849,000

Adjusted Basis. Three types of issues tend to complicate the determination of adjusted basis.

First, the applicable tax provisions for calculating the adjusted basis depend on how the property

was acquired (e.g., purchase, taxable exchange, nontaxable exchange, gift, inheritance). Second,

if the asset is subject to depreciation, cost recovery, amortization, or depletion, adjustments must

be made to the basis during the time period the asset is held by the taxpayer. Upon disposition of

the asset, the taxpayer’s records for both of these items may be deficient. For example, the

donee does not know the amount of the donor’s basis or the amount of gift tax paid by the donor,

or the taxpayer does not know how much depreciation he or she has deducted. Third, the

complex positive and negative adjustments encountered in calculating the amount realized are

also involved in calculating the adjusted basis.

Example: Jane purchased a personal residence in 1999. The purchase price and the related

closing costs were as follows:

Purchase price

$125,000

Recording costs

140

Title fees and title insurance

815

Survey costs

115

Attorney’s fees

750

Appraisal fee

60

Other relevant tax information for the house during the time Jane owned it is as follows:

Constructed a swimming pool for medical reasons. The cost was $10,000, of which

$3,000 was deducted as a medical expense.

Added a solar heating system. The cost was $15,000.

Deducted home office expenses of $6,000. Of this amount, $3,200 was for depreciation.

The adjusted basis for the house is calculated as follows:

Purchase price

$125,000

Recording costs

140

Title fees and title insurance

815

Survey costs

115

Attorney’s fees

750

Appraisal fee

Swimming pool ($10,000 - $3,000)

Solar heating system

60

7,000

15,000

$148,880

Less: Depreciation deducted on home office

Adjusted basis

(3,200)

$145,680

LIKE-KIND PROPERTY

8. A special provision relates to the location where personal property is used. Personal property

used predominantly within the United States and personal property used predominantly outside

the United States are not like-kind property. The location of use for the personal property given up

is its location during the two-year period ending on the date of disposition of the property. The

location of use for the personal property received is its location during the two-year period

beginning on the date of the acquisition.

Example: In October 2007, Walter exchanges a machine used in his factory in Denver for a

machine that qualifies as like-kind property. In January 2008, the factory, including the machine,

is moved to Berlin, Germany. As of January 2008, the exchange is not an exchange of like-kind

property. The predominant use of the original machine was in the United States, whereas the

predominant use of the new machine is foreign.

LIKE-KIND PROPERTY

9. The Regulations also provide that if the exchange transaction involves multiple assets of a

business (e.g., a television station for another television station), the determination of whether the

assets qualify as like-kind property will not be made at the business level.5 Instead, the underlying

assets must be evaluated.

EXCHANGE REQUIREMENT

10. If the exchange is a delayed (nonsimultaneous) exchange, there are time limits on its

completion. In a delayed like-kind exchange, one party fails to take immediate title to the new

property because it has not yet been identified. The Code provides that the delayed swap will

qualify as a like-kind exchange if the following requirements are satisfied:

Identification period. The new property must be identified within 45 days of the date when

the old property was transferred.

Exchange period. The new property must be received by the earlier of the following:

o Within 180 days of the date when the old property was transferred.

o The due date (including extensions) for the tax return covering the year of the

transfer.

Are these time limits firm, or can they be extended due to unforeseen circumstances? Indications

are that the IRS will allow no deviation from either the identification period or the exchange period

even when events outside the taxpayer’s control preclude strict compliance.

BASIS AND HOLDING PERIOD OF PROPERTY RECEIVED

11. The following comprehensive example illustrates the like-kind exchange basis rules.

Example: Stork & Company exchanged the following old machines for new machines in five

independent like-kind exchanges:

Exchange

Adjusted

Basis of Old

Machine

Fair Market

Value of New

Machine

Adjusted

Basis of

Boot Given

Fair Market

Value of Boot

Received

1

$4,000

$9,000

$–0–

$–0–

2

4,000

9,000

3,000

–0–

3

4,000

9,000

6,000

–0–

4

4,000

9,000

–0–

3,000

5

4,000

3,500

–0–

300

Stork’s realized and recognized gains and losses and the basis of each of the like-kind properties

received are as follows:

New Basis Calculation

Exchange

Realized

Gain

(Loss)

Recognized

Gain

(Loss)

Old

Adj.

Basis

+

Boot

Given

+

Gain

Recognized

-

Boot

Received

=

New

Basis

1

$ 5,000

$–0–

$4,000

+

$–0–

+

$–0–

-

$–0–

=

$ 4,000*

2

2,000

–0–

4,000

+

3,000

+

–0–

-

–0–

=

7,000*

3

(1,000)

(–0–)

4,000

+

6,000

+

–0–

-

–0–

=

10,000**

4

8,000

3,000

4,000

+

–0–

+

3,000

-

3,000

=

4,000*

(–0–)

4,000

+

–0–

+

–0–

-

300

=

3,700**

5

(200)

*Basis may be determined in gain situations under the alternative method by subtracting the gain not

recognized from the fair market value of the new property:

$9,000 - $5,000 = $4,000 for exchange 1.

$9,000 - $2,000 = $7,000 for exchange 2.

$9,000 - $5,000 = $4,000 for exchange 4.

**In loss situations, basis may be determined by adding the loss not recognized to the fair market value of the

new property:

$9,000 + $1,000 = $10,000 for exchange 3.

$3,500 + $200 = $3,700 for exchange 5.

The basis of the boot received is the boot’s fair market value.

AMOUNT REALIZED FROM CONDEMNATION

12. The amount realized from the condemnation of property usually includes only the amount

received as compensation for the property.6 Any amount received that is designated as

severance damages by both the government and the taxpayer is not included in the amount

realized. Severance awards usually occur when only a portion of the property is condemned (e.g.,

a strip of land is taken to build a highway). Severance damages are awarded because the value

of the taxpayer’s remaining property has declined as a result of the condemnation. Such

damages reduce the basis of the property. However, if either of the following requirements is

satisfied, the nonrecognition provision of § 1033 applies to the severance damages:

The severance damages are used to restore the usability of the remaining property.

The usefulness of the remaining property is destroyed by the condemnation, and the

property is sold and replaced at a cost equal to or exceeding the sum of the

condemnation award, severance damages, and sales proceeds.

Example: The government condemns a portion of Ron’s farmland to build part of an interstate

highway. Because the highway denies his cattle access to a pond and some grazing land, Ron

receives severance damages in addition to the condemnation proceeds for the land taken. Ron

must reduce the basis of the property by the amount of the severance damages. If the amount of

the severance damages received exceeds the adjusted basis, Ron recognizes gain.

Example: Assume the same facts as in the previous example, except that Ron uses the

proceeds from the condemnation and the severance damages to build another pond and to clear

woodland for grazing. Therefore, all the proceeds are eligible for § 1033 treatment. There is no

possibility of gain recognition as the result of the amount of the severance damages received

exceeding the adjusted basis.

ROLLOVER OF GAIN FROM QUALIFIED SMALL BUSINESS STOCK INTO ANOTHER

QUALIFIED SMALL BUSINESS STOCK—§ 1045

13. Under § 1045, realized gain from the sale of qualified small business stock held for more than

six months may be postponed if the taxpayer acquires other qualified small business stock within

60 days. Any amount not reinvested will trigger the recognition of the realized gain on the sale to

the extent of the deficiency. In calculating the basis of the acquired qualified small business stock,

the amount of the purchase price is reduced by the amount of the postponed gain.

Qualified small business stock is stock of a qualified small business that is acquired by the

taxpayer at its original issue in exchange for money or other property (excluding stock) or as

compensation for services. A qualified small business is a domestic corporation that satisfies the

following requirements:

The aggregate gross assets prior to the issuance of the small business stock do not

exceed $50 million.

The aggregate gross assets immediately after the issuance of the small business stock

do not exceed $50 million.

SALE OF A PRINCIPAL RESIDENCE—§ 121

14. Qualifying for Partial Exclusion. Partial exclusion treatment is available if the taxpayer

failed to satisfy one or more of the time period requirements, if the failure resulted from one of the

following:7

Change in the place of employment.

Health.

To the extent provided in Regulations, other unforeseen circumstances. The Regulations

address the meaning of each of these causes.

Change is the place of employment contains a safe harbor distance requirement which is the

same as the distance requirement for moving expenses (see Chapter 17). That is, the taxpayer's

new employment location must be at least 50 miles farther from the taxpayer's old residence than

the old residence was from the former place of employment. If this safe harbor is not satisfied,

then the determination is made using a facts and circumstances approach. The house must be

used as the principal residence of the taxpayer at the time of the change in the place of

employment. Employment includes the commencement of employment with a new employer, the

continuation of employment with the same employer, and the commencement or continuation of

self-employment.

Example: Seth sells his principal residence (the first residence) in June 2007 for $150,000

(realized gain of $60,000). He then buys and sells the following (all of which qualify as principal

residences):

Second residence

Second residence

Third residence

Date of

Purchase

July 2007

Date of Sale

April 2008

May 2008

Amount

Involved

$160,000

180,000

200,000

Because multiple sales have taken place within a period of two years, § 121 does not apply to the

sale of the second residence. Thus, the realized gain of $20,000 [$180,000 (selling price) $160,000 (purchase price)] must be recognized.

Assume the same facts, except that in March 2008, Seth's employer transfers him to a job in

another state that is 400 miles away. Thus, the sale of the second residence and the purchase of

the third residence were due to relocation of employment. Consequently, the § 121 exclusion is

partially available on the sale of the second residence.

For the health exception to apply, health must be the primary reason for the sale or exchange of

the residence. A sale or exchange that is merely beneficial to the general health or well-being of

the individual will not qualify. A safe harbor applies if there is a physician's recommendation for a

change of residence for reasons of health (1) to obtain, provide, or facilitate the diagnosis, cure,

mitigation, or treatment of disease, illness or injury, or (2) to obtain or provide medical or personal

care for an individual suffering from a disease, illness, or injury. If the safe harbor is not satisfied,

then the determination is made using a facts and circumstances approach. Examples that qualify

include the following:

A taxpayer who is injured in an accident is unable to care for herself. She sells her

residence and moves in with her daughter.

A taxpayer's father has a chronic disease. The taxpayer sells his house in order to move

into the father's house to provide the care the father requires as a result of the disease.

A taxpayer's son suffers from a chronic disease. The taxpayer sells his house and moves

his family so the son can begin a new treatment recommended by the son's physician

that is available at a medical facility 100 miles away.

A taxpayer suffers from chronic asthma. Her physician recommends that she move to a

warm, dry climate. She moves from Minnesota to Arizona.

For the unforeseen circumstances exception to apply, the primary reason for the sale or

exchange of the residence must be an event that the taxpayer did not anticipate before

purchasing and occupying the residence. This requirement is satisfied under a safe-harbor

provision by any of the following:

Involuntary conversion of the residence.

Natural or human-made disasters or acts of war or terrorism resulting in a casualty to the

residence.

Death of a qualified individual.

Cessation of employment that results in eligibility for unemployment compensation.

Change in employment or self-employment that results in the taxpayer being unable to

pay housing costs and reasonable basic living expenses for the taxpayer's household.

Divorce or legal separation.

Multiple births resulting from the same pregnancy.

If the safe harbor is not satisfied, then the determination is made using a facts and circumstances

approach.

Example: Dee and Don, who are engaged, buy a house and live in it as their personal residence.

They equally share the mortgage payments. Eighteen months after the purchase they cancel their

wedding plans and Don moves out of the house. Because Dee cannot afford to make the monthly

mortgage payments alone, they sell the house one month later. While the sale does not fit under

the safe harbor, the sale does qualify under the unforeseen circumstances exception.

Under this relief provision, the § 121 exclusion amount ($250,000 or $500,000) is multiplied by a

fraction, the numerator of which is the number of qualifying months and the denominator of which

is 24 months. The resulting amount is the available § 121 exclusion.

Example: On October 1, 2007, Rich and Audrey, who live in Chicago, sell their personal

residence, which they have owned and lived in for eight years. The realized gain of $325,000 is

excluded under § 121. They purchase another personal residence for $525,000 on October 2,

2007. Audrey's employer transfers her to the Denver office in August 2008. Rich and Audrey sell

their Chicago residence on August 2, 2008, and purchase a residence in Denver shortly

thereafter. The realized gain on the sale is $300,000.

The $325,000 gain on the first Chicago residence is excluded under § 121. The sale of the

second Chicago residence is within the two-year window of the prior sale, but because it resulted

from a change in the place of employment, Rich and Audrey can qualify for partial § 121

exclusion treatment as follows:

Realized gain

§ 121 exclusion:

10 months

$300,000

24 months $500,000

(208,333)

= $208,333

Recognized gain

$ 91,667

SALE OF A PRINCIPAL RESIDENCE—§ 121

15. Effect on Married Couples. If a married couple files a joint return, the $250,000 amount is

increased to $500,000 if the following requirements are satisfied: 8

Either spouse meets the at-least-two-years ownership requirement.

Both spouses meet the at-least-two-years use requirement.

Neither spouse is ineligible for the § 121 exclusion on the sale of the current principal

residence because of the sale of another principal residence within the prior two years.

Example: Margaret sells her personal residence (adjusted basis of $150,000) for $650,000. She

has owned and lived in the residence for six years. Her selling expenses are $40,000. Margaret is

married to Ted, and they file a joint return. Ted has lived in the residence since they were married

two and one-half years ago.

Amount realized ($650,000 - $40,000) $ 610,000

Adjusted basis

(150,000)

Realized gain

$ 460,000

§ 121 exclusion

(460,000)

Recognized gain

$

–0–

Since the realized gain of $460,000 is less than the available § 121 exclusion amount of

$500,000, no gain is recognized.

If each spouse owns a qualified principal residence, each spouse can separately qualify for the

$250,000 exclusion on the sale of his or her own residence even if the couple files a joint return.9

Example: Anne and Samuel are married on August 1, 2008. Each owns a residence that is

eligible for the § 121 exclusion. Anne sells her residence on September 7, 2008, and Samuel

sells his residence on October 9, 2008. Relevant data on the sales are as follows:

Selling price

Anne

Samuel

$320,000

$425,000

20,000

25,000

190,000

110,000

Selling expenses

Adjusted basis

Anne and Samuel intend to rent a condo in Florida or Arizona and to travel. The recognized gain

of each is calculated as follows:

Anne

Samuel

Amount realized

$300,000

$400,000

Adjusted basis

(190,000)

(110,000)

Realized gain

$110,000

$290,000

§121 exclusion

(110,000)

(250,000)

Recognized gain

$

–0–

$ 40,000

Anne has no recognized gain because the available $250,000 exclusion amount exceeds her

realized gain of $110,000. Samuel’s recognized gain is $40,000 as his realized gain of $290,000

exceeds the $250,000 exclusion amount. The recognized gains calculated above result

regardless of whether Anne and Samuel file a joint return or separate returns.

INVOLUNTARY CONVERSION AND USING §§ 121 AND 1033

16. A taxpayer can use both the § 121 exclusion of gain provision and the § 1033 postponement

of gain provision.10 The taxpayer initially can elect to exclude realized gain under § 121 to the

extent of the statutory amount. Then a qualified replacement of the residence under § 1033 can

be used to postpone the remainder of the realized gain. In applying § 1033, the amount of the

required reinvestment is reduced by the amount of the § 121 exclusion.

Example: Angel’s principal residence is destroyed by a tornado. Her adjusted basis for the

residence is $140,000. She receives insurance proceeds of $480,000.

If Angel does not elect to use the § 121 exclusion, her realized gain on the involuntary conversion

of her principal residence is $340,000 ($480,000 amount realized - $140,000 adjusted basis).

Thus, to postpone the $340,000 realized gain under § 1033, she would need to acquire qualifying

property costing at least $480,000.

Using the § 121 exclusion enables Angel to reduce the amount of the required reinvestment for §

1033 purposes from $480,000 to $230,000. That is, by using § 121 in conjunction with § 1033,

the amount realized, for § 1033 purposes, is reduced to $230,000 ($480,000 - $250,000 § 121

exclusion).

Note that if Angel does not acquire qualifying replacement property for § 1033 purposes, her

recognized gain is $90,000 ($480,000 - $140,000 adjusted basis - $250,000 § 121 exclusion).

If § 1033 is used in conjunction with the § 121 exclusion on an involuntary conversion of a

principal residence, the holding period of the replacement residence includes the holding period

of the involuntarily converted residence. This can be beneficial in satisfying the § 121 two-out-offive-years ownership and use requirement on a subsequent sale of the replacement residence.

Notes:

1

§ 1014(b)(6).

2

§ 2040(b).

3

§ 267(d) and Reg. § 1.267(d)–1(a).

4

§§ 267(d) and 1223(2) and Reg. § 1.267(d)–1(c)(3).

5

Reg. § 1.1031(j)–1.

6

Pioneer Real Estate Co., 47 B.T.A. 886 (1942), acq. 1943 C.B. 18.

7

§ 121(c)(2)(B).

8

§ 121(b)(2).

9

§ 121(b)(1).

10

§ 121(d)(5).

Copyright © 2009 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved.