04 Hypertenzive states in preg

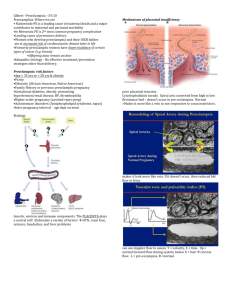

advertisement

TASHKENT MEDICAL ACADEMY DEPARTMENT OF OBSETRICS AND GINECOLOGY Hypertensive states in pregnancy Lector prof.,doctor of medicine Babadjanova G.S TASHKENT-2013 Purpose: To make out the questions of diagnostics and new methods of treatment,profilactics. Object: To give the new classification To say theories of etiology and patogenesis Clinics of difference Methods of treatment Bases of profilactic Gestational hypertension or pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is defined as the development of new arterial hypertension in a pregnant woman after 20 weeks gestation without the presence of protein in the urine. Conditions There exist several hypertensive states of pregnancy: Gestational hypertension Gestational hypertension is usually defined as having a blood pressure higher than 140/90 without the presence of protein in the urine. Preeclampsia Preeclampsia is gestational hypertension (blood pressure greater than 140/90) plus proteinuria (>300 mg of protein in a 24-hour urine sample). Severe preeclampsia involves a blood pressure greater than 160/110, with Eclampsia This is when tonic-clonic seizures appear in a pregnant woman with high blood pressure and proteinuria. HELLP syndrome This is a dangerous combination of three medical conditions: hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count. additional medical signs and symptoms. Risk factors Family history of preeclampsia Pre-existing hypertension Renal disease Diabetes mellitus Obesity Multiple gestation (twins or triplets, etc.) Age 35 or greater Adolescent pregnancy Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy The latest article in our Clinical Practice review series, Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy, reviews the potential risks associated with pregnancy among women with chronic hypertension and recommended treatment before and during pregnancy. Current recommendations regarding medications are reviewed. The prevalence of chronic hypertension in pregnancy in the United States is estimated to be as high as 3%, which represents a substantial increase over time. This increase in prevalence is primarily attributable to the increased prevalence of obesity, a major risk factor for hypertension, as well as the delay in childbearing to ages when chronic hypertension is more common. What are the risks associated with chronic hypertension in pregnancy? Women with chronic hypertension have an increased frequency of preeclampsia (17 to 25% vs. 3 to 5% in the general population), as well as placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and cesarean section. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of preterm birth and cesarean delivery in this population. How does the blood pressure of women with chronic hypertension change during pregnancy? Most women with chronic hypertension have a decrease in blood pressure during pregnancy, similar to that observed in normotensive women; blood pressure falls toward the end of the first trimester and rises toward prepregnancy values during the third trimester. As a result, antihypertensive medications can often be tapered during pregnancy What blood pressure targets are generally recommended during pregnancy? Various professional guidelines provide disparate recommendations regarding indications for starting therapy (ranging from a blood pressure >159/89 mm Hg to >169/109 mm Hg) and for blood-pressure targets for women who are receiving therapy (ranging from <140/90 mm Hg to <160/110 mm Hg). For women whose antihypertensive therapy is continued, aggressive lowering of blood pressure should be avoided, though prospective controlled trials to support these recommendations are not available. What medications are recommended to manage hypertension in pregnancy? The antihypertensive agent with the largest quantity of data regarding fetal safety is methyldopa, which has been used during pregnancy since the 1960s. Labetalol, a combined alpha- and beta-receptor blocker, is often recommended as another first-line or second-line therapy for hypertension in pregnancy. Long-acting calcium-channel blockers also appear to be safe in pregnancy, although experience is more limited than with labetalol. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors blockers are contraindicated in pregnancy. and angiotensin-receptor Risks to the Mother and Fetus Pregnant women with chronic hypertension are at increased risk for superimposed preeclampsia and abruptio placentae, and their babies are at increased risk for perinatal morbidity and mortality.8 The likelihood of these complications is particularly increased in women with long-standing severe hypertension and those with preexisting cardiovascular or renal disease.13-16 In addition, fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality are higher than normal when pregnant women have a diastolic pressure of 110 mm Hg or higher during the first trimester.14,15 Conversely, the outcomes of women with mild, uncomplicated chronic hypertension during pregnancy and of their babies are similar to those of normal pregnant women. Preeclampsia has traditionally been described as the occurrence of hypertension, edema, and proteinuria after 20 weeks' gestation in a previously normotensive woman. The differences between preeclampsia and gestational hypertension are summarized in Table 1. In general, preeclampsia is defined as hypertension plus hyperuricemia or proteinuria, and it is categorized as mild or severe primarily on the basis of the degree of elevation in blood pressure, the degree of proteinuria, or both. At present, there is no consensus regarding the definition of mild hypertension, severe hypertension, or severe proteinuria.1-6 Nonetheless, emphasis on either hypertension or proteinuria may minimize the clinical importance of a number of other disturbances in various organ systems.4 For example, some women with the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated serum liver-enzyme concentrations, and low platelet counts (HELLP) have life-threatening complications (pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, or liver rupture) but little or no hypertension and minimal proteinuria. There are 2 categories of preeclampsia, mild and severe. Severe preeclampsia is defined as the following: (1) blood pressure greater than 160 mm Hg systolic or 110 mm Hg diastolic on 2 occasions 6 hours apart; (2) proteinuria exceeding 2 g in a 24-hour period or 2-4+ on dipstick testing; (3) increased serum creatinine (> 1.2 mg/dL unless known to be elevated previously); (4) oliguria ≤500 mL/24 h; (5) cerebral or visual disturbances; (6) epigastric pain; (7) elevated liver enzymes; (8) thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000/mm3); (9) retinal hemorrhages, exudates, or papilledema; and (10) pulmonary edema. Pathophysiology One of the earliest abnormalities noted in women in whom preeclampsia later develops is the failure of the second wave of trophoblastic invasion into the spiral arteries of the uterus. As a result of this defect in placentation, there is failure of the cardiovascular adaptations (increased plasma volume and reduced systemic vascular resistance) that are characteristic of normal pregnancy. In preeclampsia, both cardiac output and plasma volume are reduced, whereas systemic vascular resistance is increased.1 These changes result in reduced perfusion of the placenta, kidneys, liver, and brain. Endothelial dysfunction (resulting in vasospasm, altered vascular permeability, and activation of the coagulation system) could explain many of the clinical findings in women with preeclampsia.4 Indeed, many of the abnormalities described in such women are due primarily to reduced perfusion rather than to hypertensive vascular injury. Mild Preeclampsia Women with preeclampsia require close observation because the disorder may worsen suddenly. The presence of symptoms (such as headache, epigastric pain, and visual abnormalities) and proteinuria increases the risks of both eclampsia and abruptio placentae; women with these findings require close observation in the hospital. Outpatient management may be considered if compliance is expected to be good, hypertension is mild, and the fetus is normal. The management should include close monitoring of the mother's blood pressure, weight, urinary protein excretion, and platelet count, as well as of fetal status.1 In addition, the woman must be informed about the symptoms of worsening preeclampsia. If there is evidence of disease progression, hospitalization is indicated. Severe Preeclampsia Severe preeclampsia may be rapidly progressive, resulting in sudden deterioration in the status of both mother and fetus, so that prompt delivery is recommended regardless of the duration of gestation. Prompt delivery is clearly indicated when there is imminent eclampsia, multiorgan dysfunction, or fetal distress or when severe preeclampsia develops after 34 weeks.Early in gestation, however, prolongation of pregnancy with close monitoring may be indicated in order to improve neonatal survival and reduce short-term and long-term neonatal morbidity. In three recent clinical trials in women with severe preeclampsia remote from term, neonatal morbidity and mortality were reduced with conservative management. Nevertheless, because only 116 women were assigned to conservative management in these trials, and because such management entails risk to the mother and fetus, conservative management must be considered only at tertiary perinatal centers and must include very close monitoring of both mother and fetus Risks of Preeclampsia to the Mother and Fetus The chief risks to the woman entailed by preeclampsia are convulsions, cerebral hemorrhage, abruptio placentae with disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, pulmonary edema, renal failure, liver hemorrhage, and death. The risks to the fetus include severe growth retardation, hypoxemia, acidosis, prematurity, and death. The frequency of these complications depends on the duration of gestation at the onset of preeclampsia, the presence or absence of associated medical complications, the severity of the preeclampsia, and the quality of medical management. In women with mild preeclampsia who are closely followed,45-48 the risk of convulsions is 0.2 percent, that of abruptio placentae is 1 percent, and that of fetal or neonatal death is less than 1 percent. The incidence of fetal growth retardation (birth weight, <10th percentile) is 5 to 13 percent, and that of preterm delivery ranges from 13 percent to 54 percent — depending on the duration of gestation at onset and the presence or absence of proteinuria. Conversely, maternal and fetal or neonatal morbidity and mortality are substantial among women with eclampsia,those with the HELLP syndrome and those in whom preeclampsia occurs before 34 weeks' gestation. Management of Preeclampsia Early diagnosis, close medical supervision, and timely delivery are the cardinal requirements of the management of preeclampsia; delivery is the ultimate cure.1,3 Once the diagnosis is established, subsequent management should be based on the initial evaluation of maternal and fetal well-being. On the basis of the results of this evaluation, a decision is then made regarding hospitalization, expectant management, or delivery, with the following factors taken into account: the severity of the disease process, the status of mother and fetus, and the length of gestation. Irrespective of the management strategy chosen, the ultimate goal must first be the safety of the mother and, second, the delivery of a live infant who will not require intensive and prolonged neonatal care. Conclusions In caring for pregnant women with hypertension, it is important to differentiate among chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia. Maternal and neonatal outcomes are usually good among pregnant women who have either mild chronic hypertension or gestational hypertension. In addition, antihypertensive drug therapy may permit such women to continue their pregnancies to term. In contrast, preeclampsia is a unique syndrome of pregnancy that is potentially dangerous for both mother and fetus; it does not respond well to the conventional antihypertensive therapy used in nonpregnant patients. Close medical supervision and timely delivery are the keys to the treatment of preeclampsia. Eclampsia The mechanism of the cerebral damage in eclampsia is unclear. The pathologic findings are similar to those of hypertensive encephalopathy. These abnormalities include fibrinoid necrosis and thrombosis of arterioles, microinfarcts, and petechial hemorrhages. In both hypertensive encephalopathy and eclampsia, the lesions are widely distributed throughout the brain, but the brainstem is more severely affected in the former, while the cortex is more severely affected in the latter. Other differences in the two conditions are that eclampsia may be seen in the absence of hypertension and that retinal hemorrhages and infarcts are rare in eclampsia. Two theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of hypertensive encephalopathy, vasospasm, and forced dilation. In the first, vasospasm causes local ischemia, arteriolar necrosis, and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. According to the second, as blood pressure rises above the limit of autoregulation, cerebral vasodilation occurs. Initially, some vessel segments dilate, and some remain constricted. Overdistention of the dilated segments results in necrosis of the medial muscle fibers and damage to the vessel wall. It is possible that both mechanisms are operant. The presence of cerebral edema in preeclampsia-eclampsia is controversial. One set of researchers stated that cerebral edema was not present in eclamptic patients when autopsy was performed within 1 hour of death and that such edema was a late postmortem change. In contrast, some others found generalized cerebral edema in some autopsy specimens and confirmed increased intracranial pressure in eclamptics with prolonged coma (> 6 hours). Early studies of cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure showed elevated pressures; however, more recent studies have failed to confirm this. Most patients with preeclampsia-eclampsia have normal clotting studies. In some, a spectrum of abnormalities may be found, ranging from isolated thrombocytopenia to microangiopathic hemolytic anemia to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Thrombocytopenia is the most common abnormality; a count of less than 150,000/uL is found in 15-20% of patients. Fibrinogen levels are actually elevated in preeclamptic women as compared with normotensive patients. Low fibrinogen levels in preeclampsiaeclampsia are usually associated with abruptio placentae or fetal demise. Elevated fibrin split products are seen in 20% of patients (usually in the range of 10-40 uL/mL). Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia without other signs of DIC may be seen in about 5% of patients, and evidence of DIC is also present in about 5%. In the past, DIC was thought to be the cause of preeclampsia; now it is regarded as a sequela of the disease. The HELLP syndrome describes patients with hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. Criteria for the diagnosis at the authors' institution are schistocytes on the peripheral blood smear, lactic dehydrogenase > 600 U/L, total bilirubin > 1.2 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase > 70 U/L, and platelet count < 100,000/mm3. This syndrome is present in about 10% of patients with severe preeclampsiaeclampsia. It is frequently seen in Caucasian patients with delay in diagnosis or delivery and in patients with abruptio placentae. The syndrome may occur remote from term (eg, at 31 weeks) and with no elevation of blood pressure. The syndrome is frequently misdiagnosed as hepatitis, gallbladder disease, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Most hematologic abnormalities return to normal within 2-3 days after delivery, but thrombocytopenia may persist for a week. Differential Diagnosis Hypertensive states of pregnancy other than preeclampsia-eclampsia. Chronic essential hypertension Chronic hypertension due to renal disease Interstitial nephritis Acute and chronic glomerulonephritis Systemic lupus erythematosus Diabetic glomerulosclerosis Scleroderma Polyarteritis nodosa Polycystic kidney disease Renovascular stenosis Chronic renal failure with treatment by dialysis Renal transplant Chronic hypertension due to endocrine disease Cushing's disease and syndrome Primary hyperaldosteronism Thyrotoxicosis Pheochromocytoma Acromegaly Chronic hypertension due to coarctation of the aorta